LEICESTER, United Kingdom — July 4 is always awkward for Americans living in Britain. Celebrating Independence Day can seem a little rude, like holding an engagement party at your ex’s house.

But this year was a little different because July 4 was Independence Day in England, too. It was the day pubs, restaurants, and hairdressers were allowed to reopen after being shut down for more than three months as part of the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown.

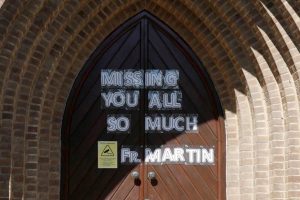

For religious believers, July 4 was also the day public worship could resume. Churches had only been allowed to open their doors for private prayer on June 15.

This serendipitous collision of the U.S. national holiday and an impromptu English one provides a timely opportunity to look at the different way the Catholic Church in the U.K. has handled the COVID-19 pandemic.

The U.K. went into lockdown on March 23, and closed all churches, even for private prayer. This was considered by some an extreme step — people were allowed to visit churches at the height of the pandemic in Italy and Ireland, for example — but, in truth, most Catholic leaders probably supported the move.

Compared to the U.S., dioceses and parishes in most of the U.K. are poor; finding funds to make sure churches were properly sanitized at all times was going to be difficult at short notice. (The Anglican Church, which has a far larger number of churches and fewer weekly communicants, even closed their churches to the clergy, who had to celebrate their livestreamed liturgies from home.)

The bishops were very supportive of the government during the first weeks of the lockdown, insisting that health and safety came first. Masses were livestreamed — itself the cause of a steep learning curve for British clerics, who don’t usually have access to the same tech support as their American counterparts — and confessions were suspended. Hospital chaplaincies continued, under restrictions, and many hospitals allowed priests to give last rites.

Most impressively, for an American, was the unity of the bishops. No one went off script about the lockdown. The archbishops of England and Wales have held regular calls and disseminated their decisions to the other bishops. When I asked several bishops pointed questions about the resumption of public worship, they told me they were deferring to the archbishops on the matter.

(By contrast, the first thing an American bishop can be expected to say about his metropolitan archbishop is usually, “He’s not my boss.”)

During the lockdown, the bishops were taking the opportunity to develop reopening guidelines, covering everything from one-way traffic through the churches to the distribution of Communion.

When the bishops thought the Church was ready, they presented the plan to the government. And when the government objected, the first signs of protest emerged.

In mid-May, the head of the bishops conference and Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Vincent Nichols, noted that the Catholic Church was ready to reopen, even if other religious groups were not (the government, seeking a one-size-fits-all solution, was worried about the worship patterns of Pentecostal congregations and many mosques, which were more conducive to virus transmission.)

Two weeks later, Cardinal Nichols called on churches to be open for private prayer. When the government began announcing plans for a greater reopening, he said Masses should also be allowed to resume at the same time. Both times, the government gave in fairly quickly.

A similar story played out in Scotland, which has its own bishops’ conference, but has been easing out of lockdown slower than England, much to the consternation of Church leaders. Northern Ireland has been moving quicker, following the lead of the Republic of Ireland.

But in all cases, the bishops in the U.K. (which has seen more than 40,000 reported COVID-19-related deaths since the start of the pandemic) have been unified and respectful, even deferential at times, to the government.

By comparison, the church reopening process seems much more confusing in the U.S. Part of the reason is the vast size of the country, as well as the fact that state governments control much of the COVID-19 response. But at an ecclesial level, it has resembled more of a free-for-all, with each diocese making its own rules.

If you go to the website of the England and Wales bishops’ conference, you will find step-by-step guides on how to celebrate each sacrament during the pandemic. It also includes the government-issued manual on how to conduct religious services in accordance with coronavirus regulations (there is no First Amendment in the U.K., so such things don’t cause a fuss.)

The U.S. bishops? There’s a prayer card and some suggested reading.

This more individualistic approach has several positive aspects: The drive-thru confessions and other creative responses to dispensing the sacraments were mostly unheard of in England.

To be fair, most English churches are small and in urban areas without large parking lots, so there was a logistics issue; but mostly it was an institutional aversion to anything that could look like rule breaking. Anti-Catholicism is still a problem in the U.K., with Catholics often accused of “disloyalty,” and Church leaders often overcompensate.

The type of verbal sparring that recently took place between the Archdiocese of San Francisco and the local government over lockdown rules, for example, just doesn’t happen with the Catholic Church in the U.K.

I live in Leicester, where our July 4 was canceled: Due to a spike in COVID-19 cases, the city was placed on an extended local lockdown until at least July 18 with less than 12 hours of notice. The local parishes dutifully relocked their doors, and the local bishop in Nottingham issued no statement, except for a request for prayer for the people of Leicester on Twitter.

One area where the Church in the U.K. has made its presence felt during the lockdown is through its charities. Catholic charitable institutions are very active in the country, and are often state supported, so many were able to continue with their work despite a fall in donations.

In many ways, British Catholics are more connected with their charities than Catholics in the U.S. The Catholic Agency For Overseas Development (CAFOD), the English bishops’ international development agency, is a household name in England in a way that Catholic Relief Services (CRS) isn’t in America.

Catholic schools in Britain have also adapted to home learning, and since they are government-funded, haven’t faced the same existential threat as Catholic schools in America.

It seems not having a First Amendment can cut both ways.