ROME — Common sense would indicate that when a citizen of a struggling country compares theirs to another, they would point to one that is in better economic shape, or enjoys more social and political stability.

But in Latin America, more often than not, those comparisons are more fatalistic: people tend to name other countries not as an example to aspire to, but as a warning.

In Argentina, for example, a common lament these days is that if things don’t change, the country will end up like Venezuela: Instead of the current 50% of the population living under the poverty line, they might end up having 90%, as is the case in the nation ruled by Nicolás Maduro.

Similarly, many in El Salvador today warn about the possibility of resembling Nicaragua.

Daniel Ortega first rose to power promising a revolution, yet almost 40 years later, many accuse him of resembling the dictator he helped bring down. Ahead of the Nov. 7 national elections, he’s made sure he’s the only contender, having imprisoned more than 30 opposition leaders in the past 45 days.

Years of popularity have allowed him to eliminate many of the legislative checks on his power, and his iron grip on the country’s security forces allowed him to quash a popular civil uprising that began in April 2018.

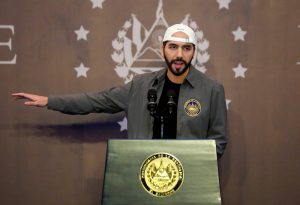

Similarly, Nayib Bukele, the young and charismatic leader of El Salvador, is facing criticism for his efforts to weaken the country’s judicial system, the prosecutors’ offices and Congress. He has done so through a series of executive actions, most of which he has communicated directly through Twitter, claiming he doesn’t trust the country’s media outlets.

As a footnote, he defined himself as the “most handsome and coolest president in the world” in a tweet back in 2019.

Though on the opposite side of the political spectrum from the democratic socialist Ortega — Bukele is a right-wing admirer of Donald Trump who describes himself as pro-family and anti-abortion — he’s been relentless in his persecution of the opposition.

Thus far, this man who arrived to power thanks to the support of the national liberation party (FMLN for its name in Spanish), the party of El Salvador’s former guerrilla, has earned praise for being a good administrator and successful in the fight against violence. But he has done so, his opponents charge, using authoritarian measures, challenging critical press coverage and the justice system.

Much like the Cuban or Venezuelan “revolutions,” Bukele claimed that the online paper El Faro, arguably the country’s online newspaper, was laundering money because it received foreign aid.

Last year, he briefly occupied Congress with a group of soldiers to pressure lawmakers to back a crime-fighting plan. Earlier this year, he forced the body to fire judges from the national Supreme Court that opposed him.

The people continue to support Bukele because he came to power as a relatively new face in his 30s. After three decades of the “old politics” that dominated the country in the wake of a bloody civil war — during which corruption and nepotism were rampant — his efforts to get rid of the old system have been relentless.

Yet having learned from the painful experiences of his peers in neighboring countries where members of the Catholic hierarchy have been threatened, shot at, and forced into exile by strongmen like Ortega and Maduro, the country’s senior Catholic prelate is sounding the alarm against his dictatorial ways, even in the face of the popular support Bukele continues to enjoy.

In a series of interviews and statements made to the press in recent weeks, Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chávez has emerged as the most vocal critic of Bukele’s El Salvador, claiming that the country is experiencing a “political earthquake” with no functioning constitutional state nor a trustworthy politician leading the country.

“Right now, democratic institutions do not work, there is no separation of powers nor democratic culture,” Cardinal Rosa Chavez said Aug. 8 amid celebrations leading up to the birthday of martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero, the country’s first canonized saint.

“This must change ... we do not have a functioning rule of law, we do not have independence of powers, we do not have a political figure to trust, we do not have a law that we have to respect, there is a very great fear that there is no law and order, therefore, there is no real justice.

“Prevailing among us is the culture of confrontation and the culture of indifference. It is urgent to combat it with the culture of peace,” he emphasized, before expressing his support for a meeting between the president and several NGOs (Non-Governmental Organizations) that advocate freedom of expression that took place Aug. 6.

Bukele refrained from engaging the prelate directly, yet several members of his party didn’t, condemning the cardinal and describing him as a “red (Communist) priest with black cassocks.”

The more the cardinal speaks, the more criticism he will receive, and more desperate will the government become in quieting him: In a country where half of the population is Catholic, and where the memory of the 1980 martyrdom of Archbishop Romero is still fresh in the collective memory, the criticism of a prelate seen by many as the successor of the murdered archbishop and known for being close to Pope Francis, is a threat few authoritarian leaders want to face.