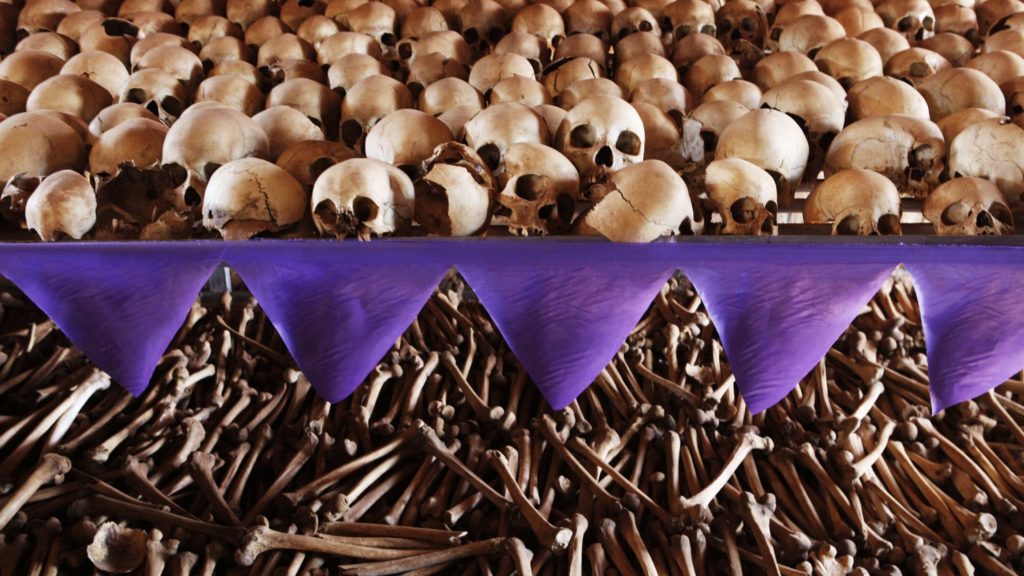

YAOUNDÈ, Cameroon – More than 1,000 corpses will be buried at the Mibilizi genocide memorial site in Rwanda on June 3. The bodies of 1,238 victims of the 1994 mass killings recently were exhumed from church-owned land, and according to a Catholic priest and diocesan official in Rwanda, the discovery of the cache of remains means the route to reconciliation is still long.

Father Théogène Ngoboka, Director of the Justice and Peace Commission of Cyangugu Diocese, carries out pastoral work in Rusizi prison, which has 3,850 inmates, of whom 1,300 are incarcerated for genocide.

“It is very deplorable, but it is our sad reality,” Ngoboka said of the newly discovered mass graves.

“During the genocide, bodies were thrown here and there. It is not surprising that bodies can still be found today, but what is very shocking is the high number of bodies that have been found in mass graves that were not revealed until now. This shows that there is still a long way to go in the process of unity and reconciliation,” he told Crux.

The following are excerpts of Crux’s interview with Ngoboka.

Crux: The remains of at least 1000 more victims of genocide were exhumed from church land in Gashonga village recently. How did you receive that news, and what does that tell you about the scale of the killings that took place some 29 years ago?

Ngoboka: It is true that the bodies of victims of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis were discovered in the fields of the Mibilizi parish (three hundred meters from the parish church). We were doing earthworks of terracing when we came across mass graves where more than a thousand bodies of victims were buried.

It is very deplorable, but it is our sad reality. During the genocide bodies were thrown here and there. It is not surprising that bodies can still be found today, but what is very shocking is the high number of bodies that have been found in mass graves that were not revealed until now. This shows that there is still a long way to go in the process of unity and reconciliation.

In my judgement these bodies have remained there for 29 years for three major reasons.

First, looking at the number of people who sought refuge but were murdered in Mibilizi during the genocide, and the bodies that have been exhumed and buried in the memorial sites in the Mibilizi area, we can see that there are bodies that have not yet been found for dignified burial. It was thought that some of the unfound bodies were dumped in rivers surrounding Mibilizi parish, but this discovery has revealed otherwise.

Second, it is noticeable that there are perpetrators of the genocide who do not yet have the good will and charity to collaborate in the work of remembrance and treatment of the past by telling the truth about what happened and especially their role. For their personal reasons they prefer to remain silent. Sensitization must continue to conscientize them.

Third, others fear that they could be sued if they reveal previously unknown information in relation to what happened during the genocide.

These challenges show us that as pastors we will have to commit ourselves more to help our sheep to walk together in the process of unity and reconciliation. Let me say here that the bodies exhumed from mass graves so far amount to 1,238 and they will be buried with dignity in the memorial site of Mibilizi on June 3.

You work with those imprisoned for perpetrating the genocide in view of helping both prisoner and survivor in the healing process. What language do you use to drive home the need for the prisoners to ask for forgiveness, and what do you tell those who were hurt to enable them forgive?

As for the language we use towards the prisoners who committed the genocide and the survivors, I would say that we are inspired by the Gospel, especially as the majority of those we accompany are believers. In the messages and conferences, we give to the prisoners we remind them that “asking for forgiveness is a remedy to free oneself, to heal oneself and at the same time to heal the whole Rwandan community that was wounded by the atrocities and consequences of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis.

In our preaching we remind the prisoners that the worst prison they can experience is that of the heart. We invite them to free themselves internally by asking for forgiveness.We remind them that after their release from prison their effective integration into the community will be made possible by their sincere request for forgiveness.

To the survivors of the genocide, we give an almost similar message inspired by the Gospel and Rwandan values, reminding them that granting forgiveness will set them free, heal their wounds, especially inner ones, and put an end to the circle of violence that could be born of resentment and revenge.

Rwandan wisdom emphasizes that to forgive is to live and to live is to forgive. In this work, we use good testimonies and success stories of those who have asked for or granted forgiveness. I will not fail to point out that the policy of unity and reconciliation put in place by our Rwandan government is a solid basis for our reconciliation work.

What would you say are the obstacles you face in this journey of reconciliation?

The obstacles to this reconciliation work are many. In my judgement the most difficult are the following:

- Lack of truth on the part of the perpetrators of the genocide

- Partial and insincere confessions by the perpetrators of the genocide

- The trauma that is still present in some survivors and perpetrators of the genocide

- Genocidal ideology and denial

- The failure to repair the damage done by some perpetrators of the genocide

- Resistance to change

- Loss of faith in some

Faced with these challenges, we are not discouraged, we continue to do our best to make our humble contribution to the reconstruction of our social fabric torn apart by the genocide. As a faith-based civil society organization, we do not have enough resources of our own and rely heavily on financial support from donors.

At the moment, these donors, who come mainly from European countries, tell us that they are affected by the war in Ukraine and the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic.