Speaking in Hungary, once the heart of Christian Europe which today is leading the charge against Pope Francis’ call for the welcoming and integration of migrants, Francis said that the Cross is, yes, an invitation to uphold Christian roots, but also a call to be open to everyone.

“Religious sentiment has been the lifeblood of this nation, so attached to its roots,” Francis said Sunday, as he was wrapping his seven hour visit to Budapest to close the International Eucharistic Congress.

“Yet the cross, planted in the ground, not only invites us to be well-rooted, it also raises and extends its arms towards everyone,” the pope said. “The cross urges us to keep our roots firm, but without defensiveness; to draw from the wellsprings, opening ourselves to the thirst of the men and women of our time.”

“My wish is that you be like that: grounded and open, rooted and considerate,” the pope said, in a clear reference to the anti-immigrant sentiment that has grown in the countries of the Visegrád group (Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic and Poland), all of which have a strong Christian identity.

Francis’ remarks came as he was delivering his last speech in Budapest, at the end of a Mass and before he prayed the Angelus, the traditional Marian prayer that popes say every Sunday when they’re in Rome, from a window in the Apostolic Palace that overlooks St. Peter’s Square.

Mostly a temporary destination for the hundreds of thousands of African and Middle Eastern immigrants who flee poverty, conflicts and climate-change related crises, these four nations, relatively small in terms of population, have imposed strong limits on new entries, even migrants and refugees on their way to reach wealthier European nations. A majority of those arriving are Muslim.

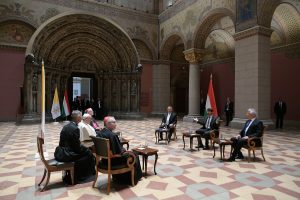

Anti-immigrant rhetoric has fueled nationalist sentiment, particularly promoted in Hungary by populist right-wing Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose views on the subject clash with that of Francis. The two had a 40-minute meeting on Sunday, together with President János Áder, at the Museum of Fine Arts. According to the Vatican’s press office, the three spoke about the role of the Church in Hungary, the commitment to the protection of the environment and the protection and promotion of the family.

Orbán, a Calvinist, was seated in the first row both during the Mass and Francis’s Angelus address. On his official Facebook page, he shared that he’d asked Pope Francis not to let “Christian Hungary perish.”

Francis spent close to seven hours in Budapest, a trip designed for him to close an International Eucharistic Congress with a Mass attended by over 100,000 people. It was the first time since Pope John Paul II closed the Congress held in Rome in 2000 that a pontiff took part in the event, which first took place over a 100 years ago.

Both the Vatican and Hungary have insisted that the reason behind the shortness of the visit compared to the three days he will now spend in Slovakia is that this was a spiritual trip, specifically for the Mass, which is what Hungary invited the pope for. However, in a classic chicken-and-egg situation, it’s unknown if the Orbán administration didn’t want the pope to stay longer, or if he avoided inviting him to spend more time on a state visit knowing Francis would refuse.

The pope’s visit to Hungary began with a behind-closed-doors gathering with the local bishops, the content of which is being kept private. It’s unclear if Francis delivered a speech, or if they engaged in a dialogue, which has been the case in the past during some of these encounters.

Later in the morning, the pontiff met with representatives of the Ecumenical Council of Churches and some Hungarian Jewish communities, where, among other things, he warned against the “threat of antisemitism still lurking in Europe and elsewhere.”

The Hungarian Jewish community, estimated at between 75,000 and 100,000, is the largest in Central Europe, with tens of thousands killed during Shoa. The trip is taking place soon after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and will close on Yom Kippur, and the pope extended his “best wishes for these feasts.”

During his remarks, the pontiff told the religious leaders that those who follow God “are called to leave certain things behind,” including “our past misunderstandings, our claims to being right while others are wrong, and to take the path that leads towards God’s promise of peace.”

God’s plans, he insisted, are always for peace and never for misfortune.

Those who follow God, regardless of their religious tradition, the pope argued, can no longer live apart, without making an effort to know one another and becoming “prey to suspicion and conflict.”

Invoking a famous bridge that’s a landmark of the Pearl of the Danube, Francis said that it doesn’t “fuse” two sides of the city together buy “holds” them together.

“That is how it should be with us too,” he told the religious. “Whenever we were tempted to absorb the other, we were tearing down instead of building up. Or when we tried to ghettoize others instead of including them. How often has this happened throughout history! We must be vigilant and pray that it never happens again.”

Francis urged those present to commit themselves to “fostering together an education in fraternity, so that the outbursts of hatred that would destroy that fraternity will never prevail. I think of the threat of antisemitism still lurking in Europe and elsewhere.”

The Eucharist, axis of the trip

After his various meetings in the Museum of Fine Arts, he went to the neighboring Heroes’ Square, where he said Mass and led the Angelus prayer, closing the 52nd International Eucharistic Congress that had opened the previous Sunday.

Predictably, the homily was centered in the Eucharist. Quoting a reading from the book of Mark, in which Jesus asks his disciples “Who do you say that I am?”

Today, Christ asks those who follow him “Who am I for you?” Francis said. “This question, addressed to each of us, calls for more than a quick answer straight out of the catechism; it requires a vital, personal response.”

Before this daunting question from Jesus, he said, “we too can be dismayed, taken aback,” since many prefer “a powerful Messiah rather than a crucified servant. The Eucharist is here to remind us who God is.”

The Eucharist, Francis said, shows “God as bread broken, as love crucified and bestowed.” Ritual elements can be added, he said, but Christ is always there, “in the simplicity of the bread ready to be broken, distributed and eaten.”

“To save us, Christ became a servant; to give us life, he accepted death,” he said. “We do well to let ourselves be taken aback by those daunting words of Jesus.”

Francis then argued that those who follow Jesus more often want a god that reigns with power, silencing enemies, because today, as it was during his time, the “cross is not fashionable or attractive.”

“We too can take the Lord ‘aside’, shove him into a corner of our heart and continue to think of ourselves as religious and respectable, going our own way without letting ourselves be affected by Jesus’ way of thinking,” he said.

“There is God’s side and the world’s side. The difference is not between who is religious or not, but ultimately between the true God and the god of ‘self’. How distant is the God who quietly reigns on the cross from the false god that we want to reign with power in order to silence our enemies!” the pope said.

Francis asked those present to find time for Eucharistic adoration, saying that Jesus can heal “our self-absorption, open our hearts to self-giving, liberate us from our rigidity and self-concern, free us from the paralyzing slavery of defending our image, and inspire us to follow him wherever he would lead us.”

Though the Mass was technically held in the Heroes’ Square, most of those in attendance flooded the Andrassy Avenue, that had several maxi-screens so that the people could follow the service. Before the Mass, Francis spent over 20 minutes greeting the faithful from the pope-mobile. There was a choir of some 800 people of all ages, from children to grandparents.

Throughout the visit, the Argentine pontiff used several greeting words in Hungarian, something he learned back when he was a young priest in Buenos Aires. According to the Hungarian Ambassador to the Holy See, Eduard Habsburg, a young Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio would regularly go to the convent the Mary Ward sisters have in the pope’s former archdiocese.

At the time, there was a group of nuns who had fled Hungary in 1956 and Bergoglio learned some basic words “flawlessly,” and he also learned to appreciate the famous Tokaji wine, which he once told Habsburg was the “most sacred thing” for Hungarians.

This is Pope Francis’ first trip since his colon surgery last July, and though he spoke of taking it easier this time around, he’ll still have a packed schedule, visiting four cities in three days in Slovakia, and delivering nine speeches before heading back to Rome soon after lunch on Sept. 15.

During the 115-minute flight from Rome to Budapest, the pontiff was visibly in good health and in a good mood, taking the time to greet each of the 74 journalists traveling with him and joking with several of them, taking so long a time that he had to be rushed to the front so the Alitalia AZ 4000 flight could land.