When U.S. immigration agents unchained Franklin Funez and he stepped off a U.S. military airplane into the heat of his native Honduras on March 20, he was still dressed in the paint-splattered clothes he had worn two days earlier on his way to drop his children at school in Texas and then drive on to the painting company he owns.

That's when local police and Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials pulled him over and put him in handcuffs.

Funez said he hadn't been allowed to call his wife and three children, who remain in the United States.

"I'm going to call them as soon as I can. But I know it's going to break my heart. I'm a father, and I have to tell my children I can't be there with them," he said.

Funez said he emigrated to the U.S. 13 years ago, and since then had done everything right, despite lacking legal status.

"I worked hard, paid all my taxes, formed a very profitable company, and last year we bought a home. It was the American dream," he said.

"We knew there was going to be a drastic change with (President Donald) Trump, and I don't have a problem with deporting delinquents. But most of us migrants are honest, hard workers, who make the American dream possible for others. If they deport us all, I don't know who's going to do the hard work," he told OSV News.

Funez said his group of deportees was "treated poorly, like dogs," by U.S. immigration officials and soldiers.

Yet his reception at the airport in San Pedro Sula was a pleasant surprise.

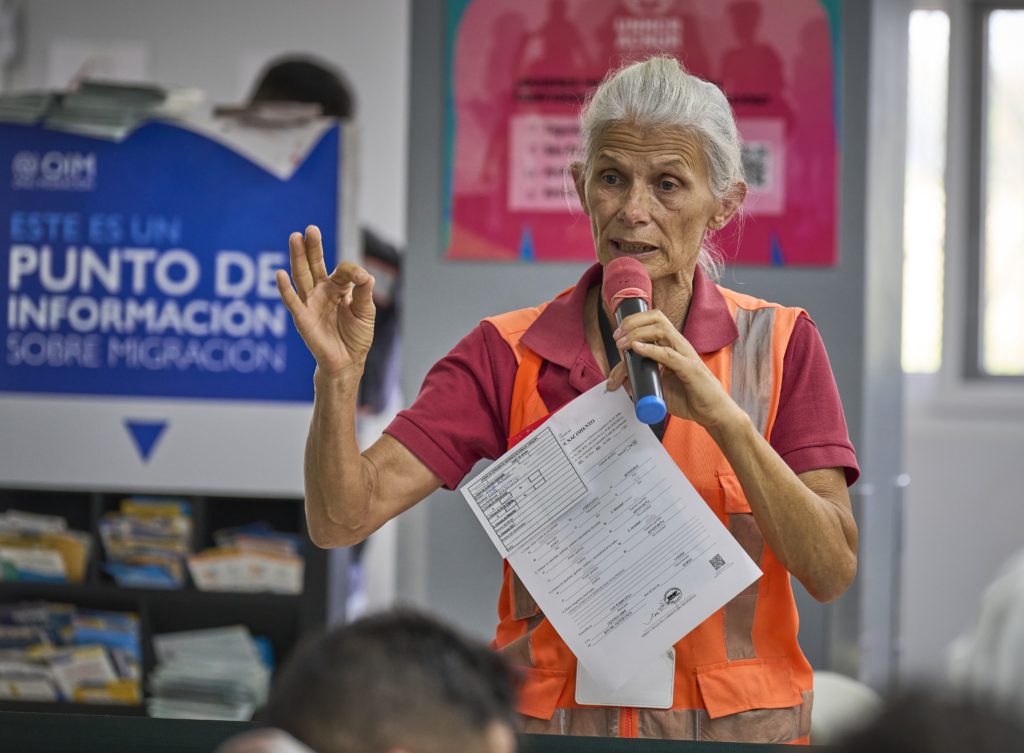

"We welcome you with open arms, like Jesus with his arms stretched wide to embrace you," said Scalabrinian Sister Idalina Bordignon as she addressed Funez and some 80 other migrants who were deported with him.

Sister Idalina, a native of Brazil, is director of the Center for Attention to Returned Migrants, a joint effort of the Catholic Church and several government and nongovernmental agencies.

As deported migrants disembark from flights, which arrive every day from the U.S. and once or twice a week from Mexico, they receive food, a quick medical check and the equivalent of $100. They also have an opportunity to speak to a mental health worker and pray in a small chapel. Immigration officials issue them identification documents. Any with pending criminal charges are taken into custody by Honduran police.

Several members of Sister Idalina's team, including a group that works with victims of human trafficking, have been forced to withdraw from the center after suffering funding cuts caused by the demise of the U.S. Agency for International Development.

"The migrants say they are treated like garbage while they're detained, so we try to welcome them as warmly as possible. As they walk in the door they receive a cup of coffee or a soft drink and some food. We give them a small hygiene kit and explain all the resources we make available to them here, as well as a small government grant that helps them buy food and supplies for their families here," Sister Idalina said.

While many simply want to be on their way, Sister Idalina said some arrive in bad shape.

"Today a man couldn't stop crying, worried about his four children left behind. He's with a psychologist now. Another woman was emotionally devastated because she was taken from her children. These are people who are grabbed suddenly at work, and they are often indignant. But it's just the latest violence they've been forced to experience. They've long lived with insecurity and hunger. They've been assaulted and abused all along the migrant trail," Sister Idalina said.

"When I was in the airplane, all I could think about was where I was going to sleep that night," said Jose Arnaldo Martinez, 73, a Honduran who lived in the U.S. for 25 years after fleeing gangs that killed his wife and children.

"If I go back home they'll kill me. So I figured I'd find a tree to sleep under, but Sister Idalina brought me to a shelter. The sister does the impossible at times to make sure that the deported feel welcomed and accepted," said Martinez, who had permission to work in the U.S. but said his documents were ignored by immigration agents.

Many in Honduras expected an increase in deportations under Trump, who promised during the campaign that he would launch the "largest deportation program" in American history. Yet Sister Idalina said the numbers haven't risen from the already high numbers under the Biden administration.

Instead, Sister Idalina said the increased threat of deportation has sown fear in immigrant communities.

"The migrants tell me that many construction sites are deserted because people are afraid to work, and that children aren't going to school for fear of being grabbed while there," she said.

Father Ismael Moreno, a Jesuit who heads a social research institute in El Progreso, predicts deportation numbers won't rise.

"They'll deport enough people in these first weeks to claim they're keeping their promises, but after that the numbers won't go up. There will be no massive deportations. But the levels of fear among migrants in the U.S. will definitely rise. If you're afraid they'll deport you, then you have to hide. You grow accustomed to living in fear," Father Moreno said.

As he arrived back in Honduras, Funez said he hadn't decided whether he would try again to enter the U.S.

He's not alone in his indecision. Sister Idalina said that while many deported migrants in the past would quickly turn around and travel north again, they are now thinking hard about their choices, as in recent weeks it has become more difficult -- and dangerous -- to travel through Mexico and attempt to enter the U.S.

Maynor Ocampo, director of a church-run migrant shelter in Choloma, said north-bound migrants are few these days. Most recently, he said, his shelter has hosted Venezuelans who had returned disheartened from the north and were heading south to look for opportunities in Colombia or Peru.

Honduras suffers both a high concentration of land in the hands of a few wealthy families, as well as high levels of corruption, Father Moreno told OSV News. That makes it unlikely that returned migrants can easily restart their lives and earn the income to which their families have grown accustomed.

"There's no political will to change anything, and without a serious proposal for agricultural reorganization here, nothing will change. The conditions that generated the original migration remain," Father Moreno said.