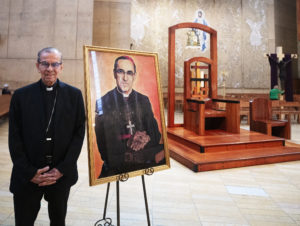

At the age of 81, Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chávez remains the best-known champion of the legacy of his friend and mentor St. Óscar Romero, who was killed 44 years ago during El Salvador’s civil war and today is considered an icon of the Catholic Church’s social justice advocacy.

In 2017, Pope Francis surprised observers by making Rosa Chávez the first cardinal in El Salvador’s history, despite only being an auxiliary bishop. A year later he declared Romero a saint, the culmination of a long, difficult effort led by Rosa Chávez.

Much has changed in El Salvador since then. In 2019, the country elected as president outsider politician Nayib Bukele, who has used heavy-handed tactics to bring sweeping changes to the country once known as the “murder capital of the world.” The most well known is the “state of exception” declared by Bukele, which has given the government emergency powers to arrest and imprison tens of thousands of suspected gang members without due process.

The result is a country almost unrecognizable compared to just a few years ago. Homicide rates have plummeted, tourism has risen, and there have been small signs of improvement in the country’s economy — all factors that contributed to Bukele’s reelection in February.

But Rosa Chávez has since emerged as the Catholic Church in El Salvador’s leading critic of Bukele’s measures, arguing that the means do not justify the ends: not only the damage to the country’s judicial system, but also the potential imprisonment of thousands of innocent young men.

Rosa Chávez visited Los Angeles in the days leading up to Romero’s March 24 feast day, where he visited several parishes — including St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Pico-Union and St. John the Baptist Church in Baldwin Park — to spend time with the local Salvadoran community.

He sat down to speak with Angelus before Mass with parishioners at St. Marcellinus Church in Commerce March 18.

Your Eminence, what brought you to Los Angeles this time?

For me, this city is very important in the history of our country. Today it’s considered the second largest city of El Salvador, because it has the largest population of Salvadorans outside of San Salvador.

So I wanted to be here with the people close to the feast day of our beloved St. Óscar Romero, March 24. I was here in 2018 for the Religious Education Congress in Anaheim and it was great to be with everyone there.

We’ve always been grateful to the help we’ve received from the Church here. I was reminded of 1986, when a large [magnitude 5.7] earthquake struck El Salvador and a plane full of aid supplies arrived to help. We will never forget that.

According to you, what would St. Óscar Romero have to say about the situation of El Salvador — and of the Church there — right now?

Let me tell you an anecdote to explain what is going on right now.

Last year, the Archbishop of San Salvador, José Luis Alas, asked me to celebrate the March 24 Mass for Romero’s feast day. “You do it, I can’t,” he said.

And I thought: “This means I have to preach. What am I going to say at that Mass?” It cost me a lot to give that homily, and I suffered a lot giving it.

A quote from Romero came to my mind: “The shepherd has to be where the suffering is.” I ended the homily with that quote. That’s the part that didn’t make the international headlines. I paid deeply for that homily, because there was a terrible attack against me as a result. But I didn’t say anything more than what I thought.

So, I had the same question: What would Romero say in this moment? That’s a subversive and demanding question, but if one doesn’t ask himself that question, he’s not a shepherd, he’s just taking the easy way out.

And being here, I also thought: What am I going to say in LA? At Mass last Sunday, March 17, at St. Thomas the Apostle Church, I talked about three countries: the El Salvador we have, the one that we want, and the one we used to hope for, the one that Archbishop Romero gave his life for.

How is El Salvador doing? You’ll get a different answer depending on who you ask. We have a great image from the outside of what El Salvador is like: that being there feels nice, feels safe. And on this, we all agree that this is the El Salvador we want: a country with justice, where everyone can fulfill their full potential, that has health care, education, employment, shelter. A country where you can have dreams, plans, feel at peace … we all want that right now.

Now, which country did Archbishop Romero want? What was his utopia of a country? He used to say: a country after God’s own heart. A country of brothers. And we’re not that country right now. We’re not a country where we’re all God’s children.

I use the image of a rainbow, which features seven primary colors, or that of the guacamaya bird [macaw] to explain that peace is composed of many colors, where we all fit together. If not, there’s no peace. That’s why it’s important to have dialogue, for each one to be able to share their own proposals, to walk together toward a common goal. This is how peace is built.

Until now that hasn’t been possible, because we have a polarized country, where there’s practically a pensamiento unico, a single line of thought. And the one who dissents ends up badly. That’s not how you build peace!

I dream of a country where the people are truly a people. There’s a famous line that says, “God wants to save us as a people. God doesn’t want a mass of people. What’s a mass of people? It’s just a bunch of persons, and the more alienated they are, the better.

And what is a people? It’s an organized community that looks for the common good. That’s what Archbishop Romero worked for. And he would tell people what was going on in the country, what needed to be thought about, what should be done … that’s what a critical, proactive laity does, it dreams of a world of justice and truth.

If you read Archbishop Romero’s last homily the day he was killed, he ends saying exactly this: to give your life to suffering, as Christ did, so that we may have a country where peace and justice reign. That was his dream. And that’s what we don’t have right now. So we need to work to make that possible in this country that’s suffering so much right now.

Some would say that in these last few years, peace has finally come to El Salvador. But others would argue that this peace has come at the expense of justice. Is it possible to have both in El Salvador?

Those who visit El Salvador feel happy to be able to walk the streets without fear, to see the beaches, the airport … and it’s true, there are reasons to feel good.

But I say this: Do any of you have the deeper life, the truth of God? Because God conquers all.

There are more than 70,000 people imprisoned [in El Salvador] under this “state of exception” from these last two years. Let’s estimate that each one has 10 people in their lives who love them: parents, family, friends. What’s 70,000 times 10? In a country of about 7 1/2 million people, that means that about 10% of the population don’t have freedom. How does this make the people suffer?

Then there are those who were removed from workplaces in the city center of the capital [San Salvador]: more than 10,000. And if one speaks, there’s fear that they could be put in jail. That is not peace. That is the peace of the cemetery, in a sense.

That’s why I am working patiently on proposals so that people don’t feel alone, so that they know they are listened to, because it’s about accompanying them. That’s the role of the Church, the role of Jesus, and that was Romero’s role. There’s an inspiration in people who want to do so much, even if in silence, discreetly, so that people can have hope.

Pope Francis, the Catholic Church, and much of the world has been following the situation in Nicaragua, where the Church is threatened in a very direct way, with a lot of concern. In that kind of situation, where do you start to look for this justice and peace?

I’ll tell you the story of Bishop Rolando [Álvarez]. He was going to leave [Nicaragua] on a plane with several others to the United States. And he decided not to get on the plane, he chose to stay with the people. He spent more than a year in prison.

I have known Bishop Rolando since he was a young priest. His gesture was marvelous: to stay with the people, to risk for the people.

But what is happening in that country? The Church is not respected there. Everything is decided by the presidential couple. And they do truly absurd things, like confiscating the Church’s material goods, and not allowing those who leave the country to reenter.

This is the reality, and it’s all totally in the hands of whatever those two people decide. This can also happen in El Salvador: the government has all the power, and no one has anyone to defend them. The way decisions are made there is almost pornographic. But in reality, they [the people of Nicaragua] need to feel accompanied by our prayer, that they may feel that they’re not alone, and that God will do the rest in his time.

Right now, Nicaragua is going through a Good Friday. Let us hope that the Resurrection comes soon.