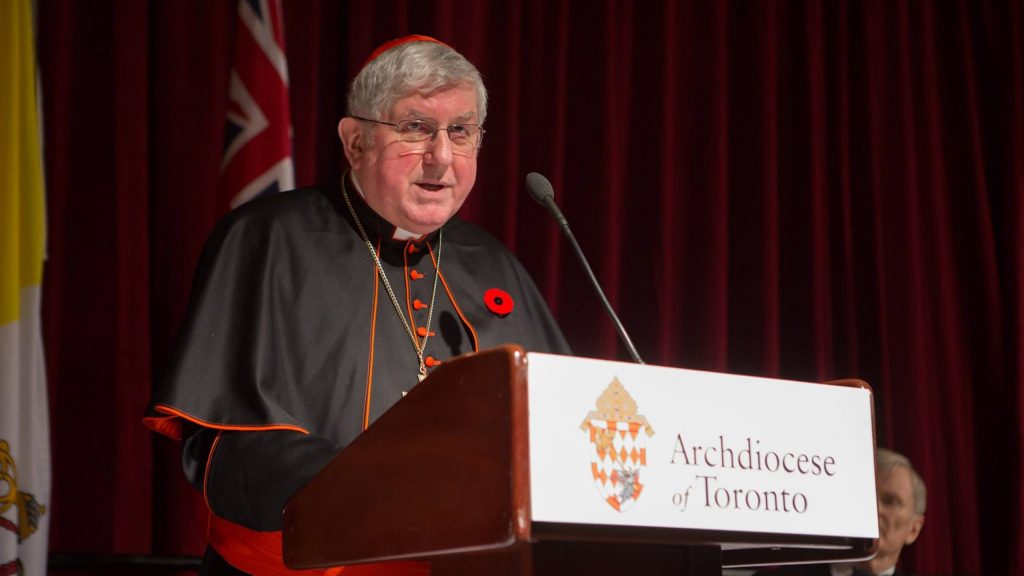

Canada is embracing “death on demand” in its healthcare laws, according to Cardinal Thomas Collins. The Archbishop of Toronto issued a strong denunciation of the Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) laws in an op-ed published Monday, March 2.

Cardinal Collins used the column in The Star to denounce Bill C-7, which would remove safeguards and expand eligibility criteria for MAiD. The bill was introduced in Parliament last week and, if passed, will create advance directives to allow patients to authorize euthanasia in advance and permit those who do not have a terminal illness to receive a physician-administered death.

“Pain medication and other resources and procedures can indeed be used effectively to medically assist people who are dying,” said Collins. “But that is not what MAiD involves: it means giving a lethal injection to people who are not dying, so that they will die.”

“Under this legislation, any serious incurable illness, disease, or disability would render a person eligible for euthanasia,” said the cardinal.

In Canada, those who are approved for an assisted death do not have to self-administer the drugs. The vast majority of MAiD patients opt for the doctor to end their lives.

Bill C-7 would also remove a 10-day waiting period between being approved for an assisted death and receiving the drugs for those who have a condition that would cause a “reasonably foreseeable” death.

Collins pointed out that if this bill were to become law, there would be waiting periods in his home province of Ontario “for gym memberships and new condominium purchases,” but not for assisted deaths.

“This is a new chapter of death on demand,” he said. “Canada has cast aside restrictions at a far quicker pace than any other jurisdiction in the world that has legalized euthanasia.”

When MAiD first became law in 2016, the Canadian government promised to do a “thorough” review prior to introducing new legislation. This did not happen, said Collins. Bill C-7 was introduced in response to a September 2019 Quebec Superior Court decision which found that the “reasonably foreseeable death” stipulation was a violation of human rights. The Canadian government said they did not wish to appeal that decision.

Collins also decried the lack of widely-available palliative care services, and questioned why there was no “political will to push forward on palliative care for all Canadians.” About a third of Canadians have access to palliative care, but medically assisted deaths are guaranteed, widely available, and fully-funded under Canada’s health law.

“If all Canadians had access to quality palliative care, fewer would seek lethal injection. Instead of developing an overall culture of care, we are rushing towards death on demand,” said the cardinal. “The same doctors who are trying to care for their patients will now be called on to approve euthanasia for them.”

In Canada, doctors are able to refuse to administer an assisted death, but must refer patients to a willing physician.

The sick, elderly, and disabled “need assisted living, not assisted death,” said Collins. “They should never be seen as a burden to our society.” He wrote that he is worried that these vulnerable populations, having suddenly become eligible for assisted death, “may well be pressured, whether from family, friends or even their own health care professionals, to ‘ease their burden’ and end their lives.”

To combat this mentality, Collins wrote, it is imperative for Canadians to “foster a culture of care and love for one another” and strive to accompany friends, family “and even strangers...recognizing the inherent dignity of every person.”