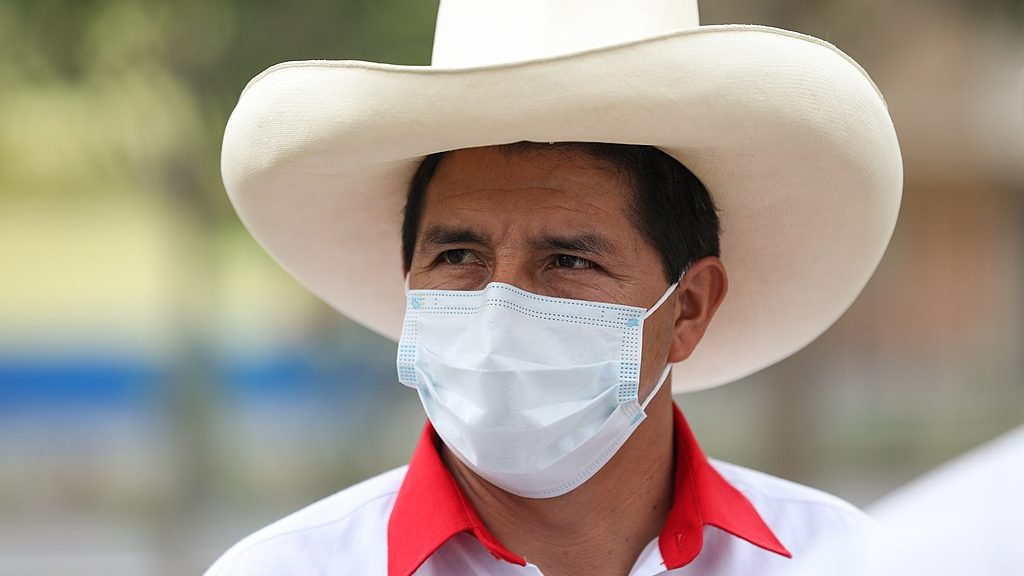

ROME — Peru’s new president, Pedro Castillo, was sworn in on July 28 in the presence of an envoy from the White House and several Latin American leaders, as well as the king of Spain, from which Peru gained its independence 200 years ago.

Though he has described himself as a Catholic and a devotee of the Virgin Mary, his party, “Perú Libre” (“Free Peru”) is Marxist. During the campaign, several bishops had to reiterate that the local Catholic Church did not support him nor his opponent, Keiko Fujimori, primarily because Church leaders are asked to steer clear of partisan politics, but also because Marxism is an atheist ideology.

A former rural schoolteacher who is holding public office for the first time in his life at age 51, Castillo has vowed to govern “for the people and with the people.” But he will face a deeply divided Congress, a reflection of the fact that he’s now the leader of a deeply divided country.

Although he won the election by a razor-thin margin of some 40,000 votes, he is not expected to be a unifying figure: He used his inaugural speech to condemn the three centuries of Spanish influence in Peru, saying that Europe developed thanks to the minerals extracted from Latin America with the blood and sweat “of our grandparents.”

“This country is founded on the sweat of my ancestors. The story of this silenced Peru is also my story,” he said.

Though the speech included many promises — and semi-veiled threats — this one in particular puts the Catholic bishops of Peru in a tight spot: Though an estimated 80% to 90% of the population is Catholic, the country’s 51 indigenous peoples comprise 45% of the total population.

Like their fellow bishops throughout South America, Peru’s bishops already have to navigate their country’s conflicted relationship with the Spanish legacy of evangelization, and with good reason: Though it is unfair to claim that the Catholic Church did everything wrong — as many historians have long claimed that without the Jesuits, Franciscans and Dominicans it’s possible that there would be no indigenous peoples left — it cannot be said either that it did everything right.

During his 2015 visit to Bolivia — a country that shares much of Peru’s history — Pope Francis acknowledged the tension directly: “I say this to you with regret: Many grave sins were committed against the native people of America in the name of God.”

He added: “I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offense of the Church herself, but also for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America.”

But on the other hand, Latin America’s social fabric has long been closely interwoven with the Catholic Church: Thousands of hospitals, schools, soup kitchens, and rehabilitation centers would not exist without the Church, leaving millions without access to health care and education. More recently, Catholics have played a key role in protecting the environment and the Amazon region. For years, the Church has been the loudest voice criticizing the global economic order for putting profits over people.

Hence the historic tightrope local bishops and politicians have been walking for decades in Peru, but also in the Venezuela of Nicolas Maduro; the Mexico of center-left Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador; and the Bolivia of former “cocalero” (“coca grower”) activist Evo Morales. Politicians continue to attack the Church for the mistakes of the past, while the institution positions itself not only as a source for spiritual strength but even as a refuge and advocate for the poor and dispossessed of the continent.

Bishops in Peru, Colombia, and Mexico have an added looming shadow: the role former guerrilla members — and active members of organized crime — have in national politics. In the case of Peru, Congress now has seven Castillo supporters who are former members of “Sendero Luminoso” (“Shining Path”), a revolutionary Communist party and former guerrilla movement that targeted clergy during its most violent period, killing several priests and religious.

In his first interview after Castillo’s inauguration, Archbishop Miguel Cabrejos, president of the Peruvian bishops’ conference, warned that “he who loves his political dream more than the country itself will end up destroying it; he loves his personal option more than the common good.”

“Peru is divided, but we have nothing to gain by defending my personal dream instead of the common dream. We need to create sincere bridges of fraternity and solidarity. We must build, not destroy,” he said.

When it comes to overcoming polarization and strengthening the integrity of the people, Archbishop Cabrejos said, “the Church plays an important role through the works of social work. We must continue to build, especially for the poorest, women, and children."

Beyond the ideological differences between the Catholic bishops and Castillo, the president can expect for the local hierarchy to not only call for dialogue, but actually show an eagerness to pull up a seat at the table. However, he should also know that they won’t remain on the sidelines and instead intervene through interviews or statements when the need arises.

If there’s one thing that Castillo can expect from Peru’s bishops, it is that they won’t give him a free pass for being a political newcomer, nor offer him support unless he starts presenting a healing vision for the future, rather than a wounded one of the past.