May 13, 1981 was a busy day – like any other – for St. John Paul II. The Institute for Marriage and Family has been established, and the pontiff had received French doctor and geneticist Jerome Lejeune.

“After lunch with Lejeune and his wife Pope John Paul II started his traditional drive among pilgrims gathered at St. Peter’s square, before the General Audience,” Włodzimierz Rędzioch recalled.

Rędzioch, known among reporters working in the Vatican as Vladimiro, is the Vatican correspondent for the Niedziela Polish catholic weekly. In 1981 was working for L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper.

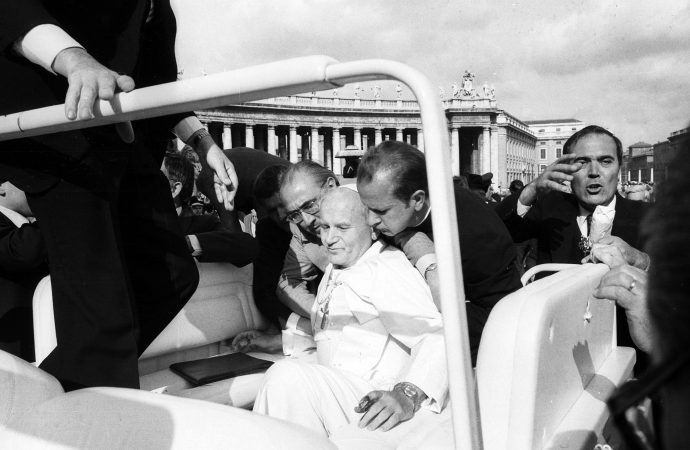

It was during this drive that John Paul was shot by Mehmet Ali Agca, a citizen of Turkey.

“I didn’t hear the shots,” Rędzioch told Crux. “I only heard that all pigeons all the sudden took flight from St. Peter’s Square.”

“The popemobile started to return, making additional swirls – probably because the security was afraid that there may be more shots,” he said.

The bullet hit John Paul in the stomach, right elbow, and the index finger of the left hand.

“He slumped into my arms. He suffered a lot,” Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, at the time the personal secretary of the Polish pope, told KAI.

“We didn’t know what happened, but pilgrims started to whisper the word ‘attentato’,” Rędzioch told Crux, remembering that the square was completely deserted by security personnel and general audience organizers.

“Only pilgrims were left present in the square. Father Kazimierz Przydatek, responsible for Polish pilgrimage groups, showed nerves of steel and started to pray a rosary,” he continued, remembering that the Polish pilgrims then put an image of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa on the chair set up for the pope in the square.

John Paul was taken to Rome’s Gemelli hospital.

Years later the saint wrote about this in Memory and Identity: “I remember the way to the hospital. I remained conscious for a while. I had the feeling that I would survive. I was suffering, there was reason to be afraid, but I had such a strange trust. I told Father Stanisław that I forgive the attacker.”

“In those moments my heart was breaking with pain,” Dziwisz told KAI. “The sight of a bloody white cassock will stay with me forever. We were shocked because the attack on the pope seemed unimaginable. We didn’t even try to give the Holy Father first aid; there was no doctor nearby. It was a race against time, especially since there was an afternoon rush in Rome, and the city was jammed. Fortunately, the ambulance reached the Gemelli hospital very quickly.”

Rędzioch remembered it was at 6:58 pm when he heard the news that the pope’s vital organs hadn’t been hit. He was constantly moving between Polish House and the Vatican’s press office, both located near St. Peter’s Basilica.

“At 11:30 pm we were told the news that the operation has ended and now we have to wait,” he said.

Rędzioch and many Polish immigrants and their compatriots at home who were hoping that John Paul II was the one who would bring changes to communist-ruled Poland and the Eastern European bloc. These hopes were millimeters from crumbling. Two weeks after the assassination attempt, when pope was still in the hospital, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński died in Poland – offering all the prayers that people said for his own recovery – to the suffering pope.

Wyszyński, the Primate of Poland, was a spiritual father for Karol Wojtyła who once said there would be no Polish Pope without the primate. Both were vigorous critics and peaceful fighters of the communist regime.

Wyszyński is scheduled to be beatified on Sept. 12, 2021.

Dziwisz has no doubt the Soviets were behind the assassination attempt, even though the role of KGB was never officially proven.

“From the perspective of the years and events related to the collapse of these systems, to which, after all, the Holy Father contributed, we can say that the powers built on human harm and oppression will want to use the same methods to get rid of the man who seemed to be threatening their absolute power.”

Rędzioch remembers a conversation with Cardinal Andrzej Deskur, one of the closest friends of John Paul II who on the very day of the conclave in 1978 experienced a stroke that left him paralyzed until his death in 2011.

“Cardinal Deskur told me that he’s not interested which hand was used to shoot the pope – he was convinced that it was the devil who was behind the attack on John Paul,” he recalled, adding: “I understood at that moment that the details of the attack are not important, that this attack is part of the eternal struggle of the Evil One with the Church of Christ.”

While recovering at the hospital, John Paul realized that the date of the attack was not accidental. It was May 13, 1917, when the Virgin Mary appeared to three children in Fatima.

A Slovak bishop, Paweł Hnilica, brought the Fatima documentation to the pope, who at the time was unaware of the full details of the predictions made during the Fatima apparitions.

A year later, John Paul II traveled to Fatima to thank Virgin Mary for saving his life. He placed a bullet meant to kill him in the crown of Mother of God, marking a new beginning of one of the most powerful Marian devotions in the world.