ROME — Since his election to the papacy in 2013, Pope Francis has been dubbed a “pope of firsts” by Vatican observers, starting with who he is: the first pope from the Americas, the first Jesuit pope, and the first to take the name Francis.

Now, there’s a very real chance that, if the ongoing campaign lobbying for him to visit the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv succeeds, he’ll add another historic “first” to his legacy: the first pontiff in modern times to travel to a country being invaded by a foreign nation.

The one pope who came the closest was St. Pope John Paul II. In 1994 (year three of the four-year war in Bosnia), he tried to go to the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo, epicenter of the conflict.

In a recently published book on the history of the Balkan conflict, Italian historians Francesco Battistini and Marzio G. Mian quote the papal nuncio to Bosnia and Herzegovina at the time, then-Archbishop Francesco Monterisi, as recalling that he was summoned several times to Rome, where “the Holy Father confided in me that he saw it as an epoch-making journey. The problems, however, emerged immediately. The Serbs did not want to."

Pope Francis is likely faced by a similar situation. He has said publicly that he could visit Kyiv, and many Ukrainians are desperately calling on him to do so. But Russia, it’s safe to assume, would not want the pope setting foot in a country it has invaded.

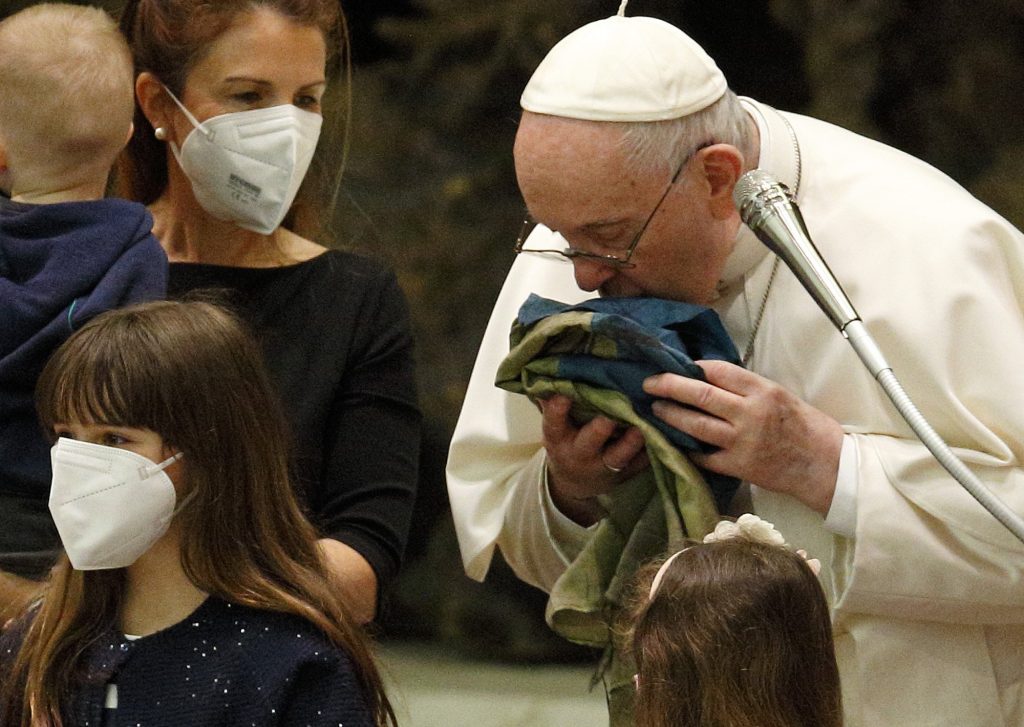

Judging by his words during his April 2-3 trip to Malta, Pope Francis’ heart and mind seem to be on Ukraine. Days later, at this weekly general audience in the Vatican April 6, he kissed a yellow and blue flag that has seen better days.

“It comes from war,” Pope Francis explained. “It comes from the martyred city of Bucha” outside of Kyiv, where images of dead Ukrainians allegedly tortured and executed by Russian forces in past weeks have international accusations of war crimes.

The pontiff denounced the “increasingly horrendous cruelties [that] are also committed against civilians and defenseless children. They are victims whose innocent blood cries out to the heavens and implores: Put an end to this war, silence the weapons, stop sowing death.”

Starting on Feb. 27 — his first public appearance following the Feb. 24 Russian invasion of Ukraine — Pope Francis has spoken at least four times a week about the conflict, calling it a “monstrosity,” “cruel,” “senseless,” “blasphemous,” and demanding war be abolished before it “abolishes mankind.”

In all this, the pope has avoided naming Russian President Vladimir Putin. But on his trip to Malta, the pope spoke of “some potentate” who, caught up in “anachronistic claims of nationalist interests, is provoking and fomenting conflicts.”

“Now in the night of the war that is fallen upon humanity, please, let us not allow the dream of peace to fade,” he said.

The pope and his diplomatic team have pledged to do everything and anything within their power to help stop the war. Yet for many of those personally impacted by the conflict, it is evident that condemning the invasion in the strongest possible terms and back-channel diplomacy through the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Kirill and the Russian ambassador to the Holy See, have not been enough.

In comes the ongoing campaign for Pope Francis to go to Kyiv. He has been invited by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the capital’s mayor, and Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. (The latter has been saying at least since December that a papal visit could stop the war.)

The pontiff himself stoked the fire during the Malta trip, saying twice in 36 hours that a visit to Kyiv is “on the table.”

“We are working so that the visit of the Holy Father to Ukraine will take place,” Shevchuk told journalists hours after the pope’s comments. “We would like him to come to Ukraine as soon as possible. His visit to Ukraine during the war could be a powerful gesture of peace.”

Andrii Yurash, Ukrainian ambassador to the Holy See, echoed the sentiment during an interview with Crux: “It would be a message to end the war,” he said.

Regarding the security concerns that surround such a visit, the ambassador said that Ukraine would do absolutely everything in its power to guarantee his safety, and that he was confident that “Russia would too,” as the pope being killed in Kyiv would be “their end in the civilized world.”

Ambassadors of European countries, he said, have pledged the help of their nations if the pope decided to make the trip.

For each voice urging the pope to travel, however, there is one arguing that it is not yet safe, nor prudent, as it would shatter any possibility of real diplomacy.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, NATO has avoided sending troops, arguing that it would mark the end of dialogue and the beginning of World War III. That is where the big question lies: To a leader like Putin, would the pope marching into Kyiv represent an olive branch or a further provocation?