The Vatican press office confirmed earlier this month that Pope Francis will be going to Malta this April, a trip he had promised to make in 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic forced him to postpone.

Before the pandemic, Pope Francis was averaging three “major trips” each year, especially to Africa, Asia, and the Americas. He’d also taken a couple of day trips or overnight visits to a European country, but had so far managed to avoid the “big ones” such as the United Kingdom, Spain, France, or Germany.

Based on what the pope and those close to him have said, this trend for papal traveling will continue, as long as the pandemic and his health allow it.

In addition, there are other trips in the roster for the pontiff, who is often described as a “man in a hurry.”

The ones in the peripheries

Going to the global “peripheries” has been a central focus of Pope Francis’ pontificate, and he has expressed an interest in visiting four such countries in particular: Papua New Guinea, East Timor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and South Sudan.

If a visit to Eastern Asia materializes, Pope Francis might try to keep the schedule he’d first spoken about in 2020, while also adding Indonesia. While the papal representative from East Timor said last year that a visit from Pope Francis had been penciled down for January 2022, it has yet to happen.

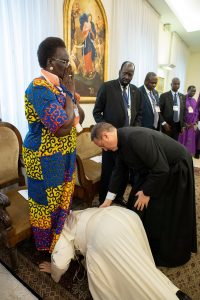

When it comes to Africa, it was the Archbishop Justin Welby, head of the Anglican communion, who said Feb. 4 that he might be visiting South Sudan “in the next few months, maybe a year.” The two want to go together to return the 2019 visit made by the country's five top leaders to the Vatican, when Pope Francis made history by kneeling down, kissing the politician’s shoes, and telling each one of them, “I beg you, make peace.”

The thorny one

Pressure is mounting for Pope Francis to visit Canada after the discovery of hundreds of unnamed graves in schools financed by the state but run by the Church.

More than 150,000 indigenous children were forced to attend these schools, forbidden from practicing their culture, and often subjected to physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

There were 139 schools in the system, which ran for over 150 years until 1996. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates that approximately 4,100 to 6,000 children died amid abuse and neglect while in the residential school system.

The Vatican said on Oct. 27 of last year that the pope is willing to travel to Canada after receiving an invitation from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, which potentially sets the stage for a papal apology.

Those in crisis

Pope Francis is known for being a man who doesn’t mind a bit of danger when traveling. In fact, he may have become the first pope to visit a country in the throes of an ongoing civil war: When he traveled to the Central African Republic in 2015, there was a chance the Alitalia pilot wouldn’t be able to land. Pope Francis reportedly told him that if landing wasn’t a possibility, then he would parachute down there. It was a joke, of course, but like most Argentinians, he’s hardheaded enough that his entourage thought he would have.

There are currently two countries facing conflict that are in the list for the pope: Ukraine and Lebanon.

Pope Francis has spoken about wanting to visit the land of the Cedars repeatedly, moreso since the 2020 Beirut explosion. Much like he did when he wanted to visit Colombia, which was struggling to put an end to a five-decades-long civil war, he’s dangling the possibility of the visit as a carrot: If Lebanon is able to form a lasting government, he will be on the next plane out.

Beyond the spiritual element of such a visit, there is an economic reason for Lebanon’s desire to welcome the pope — being at the center of the global agenda for a few days and for a good reason could generate a big boost from tourism.

The Lebanese people want a transparent, lasting government, and want to begin to turn the page from the worst economic crisis they have seen in decades. A papal visit would surely help.

Ukraine, on the other hand, is a country Pope Francis is speaking about weekly, begging for peace in an attempt to deter Russia from escalating the ongoing invasion. Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, recently told reporters that a papal visit would signify an end of the war. And he had said last year, before Vladimir Putin mobilized some 100,000 Russian soldiers to the border, that Pope Francis might visit as soon as this year. Though the pope hasn’t announced a visit, it’s a place that’s top of mind.

Though from an ecumenical perspective it might cause the Holy See a bit of a headache with Russia, there are arguably few Eastern Churches in communion with Rome that have suffered as much in the past century as the Ukrainian one. The Soviet Union tried its best to annihilate them, and almost succeeded, save for those who kept the faith alive underground.

The easy one

Spain marks two big anniversaries for the Catholic Church this year: the conclusion of the Ignatian Year on July 31, and the closing of the two-year Jubilee Year of St. James, to be celebrated in Santiago de Compostela.

Pope Francis had expressed interest in taking part in the celebrations for the Ignatian Year, as it’s a major celebration of the Jesuits, his own religious order. But a visit might be politically thorny, as he would have to engage with the leaders of a socialist country that is far from the “Espana la Catolica” (“Spain the Catholic”) it once was.

On the other hand, visiting Santiago de Compostela, a pilgrimage city far from Madrid and the Spanish government, could help him avoid any controversies.

The coronavirus might have slowed down this “man in a hurry,” but if Pope Francis has his way, he could be boarding a plane to these countries or some surprise locations soon enough.