While the COVID-19 pandemic has shut down or slowed most businesses, it does not appear to have put a dent in human trafficking, said Callista Gingrich, U.S. ambassador to the Holy See.

In fact, the financial difficulties many families face around the world actually make people more vulnerable to traffickers' offers of quick cash or false promises of good jobs in other lands, said speakers at the U.S. Embassy to the Holy See's symposium Oct. 14, "Combatting Human Trafficking: Action in a Time of Crisis."

Faith-based organizations "are among some of our best partners" in the push to end trafficking and assist the victims, Gingrich said, pointing specifically to Talitha Kum, the international network involving some 2,600 women religious and their collaborators around the world.

Loreto Sister Patricia Murray, executive secretary of the women's International Union of Superiors General, said the poor who are susceptible to traffickers are "doubly vulnerable" during the pandemic, when many more families are facing hunger.

"It's estimated that an additional 130 million (people) will fall below the poverty line this year, and I suspect that that is an optimistic figure," she said.

Comboni Sister Gabriella Bottani, coordinator of Talitha Kum, said that in 2019 the members of the network provided direct assistance -- rescue, housing, education and psychological support -- to 24,700 survivors.

"Each one of these is a story of an encounter of sisters and survivors," she said.

The COVID-19 pandemic, Sister Bottani said, has been a magnifying glass that has highlighted the inequality and injustices that make some people easy prey for traffickers.

"Protective protocols of hygiene and social distancing are reserved for the privileged," she said, since the poorest of the poor have no choice but to go out seeking ways to earn money and often do not have access to running water, let alone hand sanitizer.

Trafficking in persons ultimately is the result of an economic system based only on consumption and on valuing human beings according to the wealth they can produce for another, she said. "It's a cry for conversion, for deep change" at a personal, social, national and international level.

The pandemic and its lockdown, she said, not only increased poverty, but also increased acts of violence against women and children held by traffickers, increased online pornography with its exploitation of women, children and adolescents, and it left many migrants who had been trafficked for work stranded and with nothing.

Olga Zhyvytsya, international advocacy officer at Caritas Internationalis, added that the lockdown and travel restrictions meant that victims of trafficking have had fewer opportunities to escape or attract the attention of someone who can help.

Kevin Hyland, a former London police officer and longtime anti-trafficking campaigner, told the symposium that "symptoms of human trafficking are evident in every nation, every city and town," yet individuals and governments seem to do very little to stop it. At times, they even seem to turn a blind eye to it, for example, with trafficking for prostitution or for domestic work.

"The notion that human trafficking is inevitable," he said, has resulted in it being so.

Princess Okokon, a Nigerian who survived trafficking and now helps other survivors in northern Italy, said traffickers who exploit women for the sex trade treat them "like an ATM, and when the ATM runs out of cash, they discard them."

She told the conference that just as traffickers have recruiters in poor communities, especially in Africa, it is important that groups like Talitha Kum and, especially, survivors work in those communities, warning people about the way recruiters operate and the lies they tell.

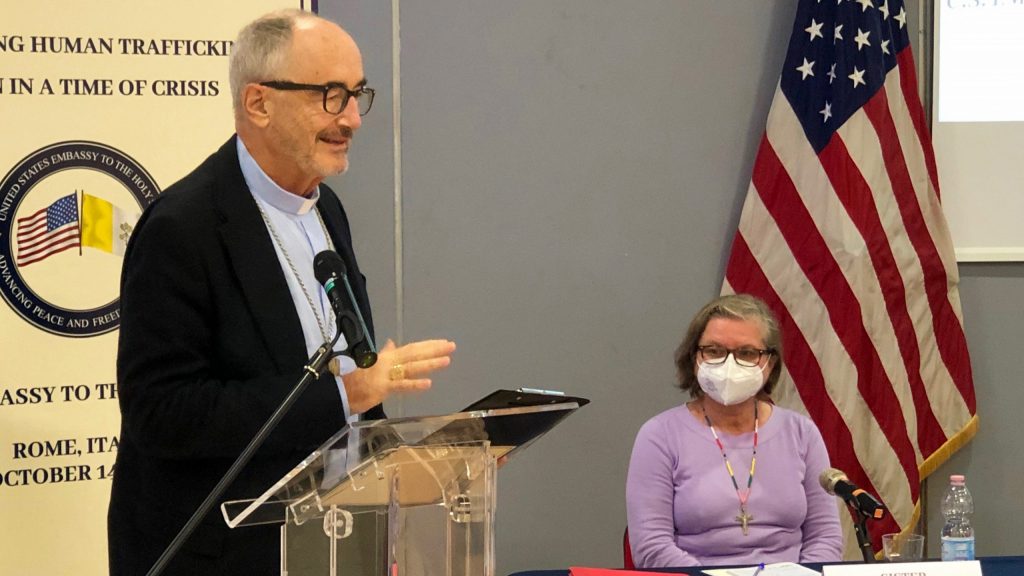

Cardinal Michael Czerny, undersecretary at the Migrants and Refugees Section of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, told symposium participants that "the biggest, basic problem" is that while a few people in churches, governments and nongovernmental organizations are dedicated to fighting trafficking, much of the world seems not to know human slavery still exists.

When some people in the world are lacking the most basic things necessary for their survival and, therefore, are prey to traffickers, those who have enough to survive should be ashamed, the cardinal said. The people who turn to traffickers are looking for survival for themselves and their families, and until everyone decides that such dire poverty is unacceptable, trafficking will continue.

"Before we even mention trafficking, the way in which our world is not functioning should be a social shame," he said.

Cardinal Czerny framed his comments in the context of Pope Francis' latest encyclical, "Fratelli Tutti, on Fraternity and Social Friendship," and its call for all people to recognize how they are interconnected and interdependent and how their lives and lifestyles impact the poorest of the poor.

A lack of housing, health care, work and education are related to the rates of human trafficking, he said, and they must be addressed in an interrelated way.