ROME — Synods of Bishops have been held periodically at the Vatican since 1965, and, to be honest, for most of that span they haven’t been many people’s idea of a good time. Privately, they’ve been described as an expensive talk shop, full of weeks of speeches and lacking the power to do anything beyond fairly predictable recommendations to the pope.

How tedious can a synod get?

Well, consider that in 2012 Pope Benedict XVI convened a Synod of Bishops on the New Evangelization. It took place while violence was escalating in Syria, and at one point it was decided the synod should dispatch a special delegation to the country to express its concern.

The roster was put together at the last minute, with then-Secretary of State Italian Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, running around immediately before the announcement was to be made to ask prelates if they’d agree to go.

One such invitee was Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York. When Bertone asked if he’d pack his bags to take a hardship trip to a war zone, Dolan didn’t miss a beat: “Your Eminence,” he said with his trademark grin, “I’d do anything to get out of coming to the synod!”

(The idea, honestly, was a bit half-baked, and due to logistical and security concerns the delegation never got off the ground, so Dolan was stuck sitting in the hall anyway.)

In the Pope Francis era, synods have become somewhat more dramatic affairs, since the pontiff tends to use them to road-test big ideas. In the 2014 and 2015 synods on the family, it was his cautious opening to Communion for Catholics who divorce and remarry outside the Church; this time around, with the Oct. 6-27 Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region, it could be married priests to serve isolated rural communities.

Still, most people will tell you that sitting in a stuffy synod hall all morning and afternoon, listening (or not, as the case may be) to a seemingly endless series of “interventions” — which sounds like a medical procedure, but is actually Vatican-speak for a talk — isn’t exactly dancing in the moonlight, no matter how monumental the subject matter.

That said, there’s a glass-half-full case for the value of a synod, which has precious little to do with anything that goes on during its formal sessions.

In effect, a Synod of Bishops is like a graduate seminar in the global realities of Catholicism, bringing together people from all over the Catholic world in close quarters for three weeks and giving them a chance to swap stories, share experiences, and get a sense of what it’s like to walk in the other guy’s shoes.

If you were to poll all of the roughly 300 participants in the current synod, including bishops, clergy, religious, lay experts, and observers, asking them what their favorite part is, it’s a good bet that at least 70 percent would say “coffee breaks.”

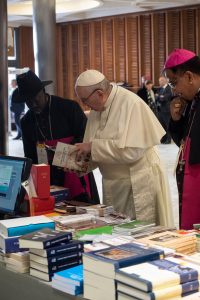

Each morning and afternoon, the schedule includes a half-hour for coffee, which is the motor fuel of any Italian gathering. People exit the hall and gather around large tables in the atrium of the Vatican’s synod hall, grabbing a coffee and something to nibble on, and then pass the time chatting with one another.

It’s not at all unusual to see a cardinal from Peru, for instance, talking with a lay scientist from France, or a bishop from the U.S. chatting with an indigenous activist from Bolivia.

One novel feature of the Francis years is that more often than not, one of the people out in the hall slapping backs and yucking it up is the pontiff himself. When Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Galveston-Houston took part in the first synod on the family, I once asked him how a particular morning session had gone.

He couldn’t remember much from the floor debate, but he described going out for coffee and accidentally bumping into someone as he turned to leave. “My God,” he said, still astonished, “I looked up and it was the pope!”

Such exchanges aren’t confined to coffee breaks, either. Synod participants also network during their down time, sometimes grabbing a quick lunch with one another at an eatery near the Vatican.

If you were to walk down a nearby avenue called the Borgo Pio around 2:30 p.m., which is smack dab in the middle of the Roman lunch hour, you could probably put together a quorum from the synod simply by rounding up all the members sitting outside at one or another of the cafes that line the street.

When the day’s work is done, people can venture a bit farther afield. Vatican cardinals will sometimes host dinners in their apartments, while other times synod participants will be invited to dinners at Roman restaurants.

It’s likely that at least once this month, members of the synod who’ve never done it before will dine at L’eau Vive, a restaurant near the Pantheon run by the “Missionary Workers of the Immaculate,” a group of consecrated laywomen, where the service is interrupted every night at 10 p.m. to sing the “Salve Regina.”

Do Synods of Bishops produce drastic change in the here-and-now? Probably not, even under a pope who takes them seriously, like Francis.

However, you can always tell the difference between an American bishop who’s taken part in a synod at least once in his life and one who hasn’t. The former generally thinks in a more global key about the Church, and he’s more sensitive to how solutions that seem no-brainers to Americans may not play so well in Delhi or Dubai.

One could ponder, perhaps, whether that’s enough to justify the exercise. Yet in a 21st-century Church in which two-thirds of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics live outside the West, and where Americans account for just 6% of the total Catholic population, it’s certainly not nothing.