ROME — Over the years, no aspect of Vatican diplomacy has generated as much consternation as its mania for impartiality. From the alleged silence of Pope Pius XII on the Holocaust during World War II to Vatican discretion today on China’s human rights record, the desire not to be seen as taking sides, in the eyes of critics, too often has left Rome feckless in the face of tyrants, dictators, and thugs.

Yet to understand where that imperative of non-alignment comes from, one need look no further than the current conflict in Gaza.

The Vatican would love dearly to position itself as a bridge-builder between Israelis and Palestinians, not only to put out the immediate fires in Gaza and East Jerusalem but to resolve the underlying tensions, famously described as the “mother of all conflicts.” For decades, the Vatican has seen ending the Israeli/Palestinian dispute as geopolitically essential to world peace and pastorally key to the survival of religious pluralism, including Christianity, across the Middle East.

Unfortunately it probably can’t act as a mediator and is unlikely even to try, because it’s not truly seen as a neutral party by all sides.

The plain fact of the matter is that even if you could somehow magically get all the disparate players on the Palestinian side to agree, the Israelis probably wouldn’t go for it, and that’s for three primary reasons.

First is history, meaning the legacy of centuries of Christian anti-Semitism and the perception that the Vatican stayed on the sidelines during the Holocaust, even allowing the Jews of Rome to be rounded up and shipped off to the camps without protest. While there’s an active historical debate over the role of Pius XII during the war, and a strong case that he did what he could under excruciating circumstances, the common perception among many Jews and Israelis is that the Vatican took a pass when they needed it to get involved.

If that’s your view of an institution’s past, it’s perhaps understandable that if it comes along now offering to lend a hand, the idea might be met with skepticism.

Second, there’s the equally widespread Israeli view that the Vatican leans toward the Palestinians in today’s politics, in part because the bulk of Catholics in the Middle East, as well as the clergy and the hierarchy, are Arabs. In the Holy Land they’re mostly Arab Palestinians, and in general they share the same resentments and perspectives as other Palestinians.

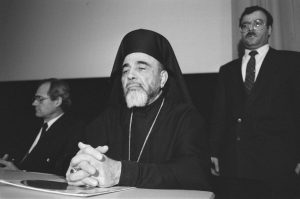

In some cases, that pro-Palestinian bias among the local hierarchy is the stuff of legend. Israelis have long memories, and they haven’t forgotten Greek Melkite Archbishop Hilarion Capucci, who was arrested in 1974 for smuggling Kalashnikov rifles, pistols and dynamite to the Palestinian Liberation Organization in the trunk of his own car. Archbishop Capucci was sentenced to 12 years in an Israeli prison and liberated in 1978 only after a personal appeal from St. Pope Paul VI.

While virtually no other Middle Eastern Catholic hierarch would go that far, there’s no doubt they tend to be advocates of the Palestinian cause. Typical in this regard is a recent statement on the violence in Gaza from Cardinal Bechara Rai, the Maronite patriarch of Lebanon, who denounced “Israel’s violations in Jerusalem and its attacks on the Palestinian people.”

Cardinal Rai deemed those Israeli aggressions “an evasion of international charters and laws and a persistent transgression of international legitimacy decisions that define the correct frameworks and concepts for permanent peace.”

Even though the Israelis know the Vatican tries to maintain a balanced outlook, they also know Rome won’t go too far toward disowning their leadership on the ground. This is a situation in which little things matter, and it doesn’t escape Israeli attention, to cite just one example, that whenever Catholic bishops gather in Rome for a synod and pray in a small chapel just off the main hall, they’re kneeling in front of Stations of the Cross that were a gift of Yasser Arafat to St. Pope John Paul II.

From a certain Israeli point of view, therefore, asking the Vatican to intervene in the conflict would be like asking a judge whose family works for Pepsi to arbitrate a dispute with Coke.

Third, there’s also a long-running dispute between the Israeli government and the Vatican over the implementation of the 1993 Fundamental Agreement, which led to the establishment of diplomatic relations.

The idea at the time was that a side agreement would follow within two years to regulate the tax and legal status of Church properties in Israel, avoiding the prospect of crippling tax bills from local Israeli municipal authorities. Yet almost 30 years later no such agreement has been achieved, despite the creation of a special bilateral commission and periodic rumors that a deal is right around the corner.

Though officials on both sides in the negotiations are unfailingly polite in public, privately they tend to blame one another for the inability to reach a conclusion. Vatican officials say the Israelis want to impose their will, exalting municipal whims over international agreements, while Israelis say the Vatican wants special treatment that sets a financially unsustainable precedent if other groups were to demand the same thing.

This dispute may not be well known among the general public, but in the corridors of power in Israel, it’s another reason to be leery of the Vatican.

In other words, for a variety of reasons — none of which are really the fault of Pope Francis or today’s generation of Vatican diplomats — many Israelis just aren’t convinced the Vatican is truly neutral.

If you want to know why the Vatican works so hard not to seem aligned, that’s why, so it doesn’t end up seeming partial, when its impartiality is the one thing that might make a difference.