ROME — The Synod of Bishops, a summit of roughly 300 prelates from around the world the popes have now summoned 28 times since it was created after Vatican II in 1965, are always a bit like the Iowa Caucuses of the Catholic Church.

It’s just about the only time, at least in the early phases of the race, that all the “candidates” to become the next pope are on display for an extended period of time, which means it tends to be a moment when Church-watchers get into the traditional parlor game of speculation about what, and who, might come next.

To be honest, there really wasn’t a lot of “next pope” talk in Rome this October, during the monthlong Synod on Young People, Faith, and Vocational Discernment. Mostly that’s a reflection of the fact that there’s no health crisis around Pope Francis, and no sense that the drama of this papacy is coming to an end anytime soon.

Still, Francis will turn 82 in December, and it’s inevitable that people are at least pondering “what if?” scenarios.

Before proceeding, let’s deal with the traditional eye-rolling exercise that always comes up whenever anyone talks about this topic out loud. To wit, there’s always going to be that person who objects, “Anyone who knows doesn’t talk, and anyone who talks doesn’t know.”

Sorry, but hogwash.

First of all, no one right now “knows.” There is no secret compact that’s already determined the result of the next papal election, and frankly, cardinals are generally reluctant to talk about these things outside their narrow circles of trust, even among themselves, for fear of appearing disloyal.

Most will only wake up to making concrete choices when the time comes, so for now, speculation about what might happen is legitimate.

Second, it’s a myth to assert that one can never see the next pope coming. In the last six papal elections, a real surprise only prevailed twice — Angelo Roncalli as John XXII in 1958, and Karol Wojtyla as John Paul II in 1978.

Other than that, the men elected were either clear front-runners — Giovanni Battista Montini as Paul VI in 1963, Joseph Ratzinger as Benedict in 2005 — or at least on most people’s “B” lists, which was the case for both Albino Luciani as John Paul I in 1978 and Jorge Mario Bergoglio as Francis in 2013.

OK, Roman handicappers aren’t infallible, but they’re not blind either.

Over the last month, I’ve discussed this question with some three dozen people, sometimes one-on-one and sometimes in groups, from a variety of different cultural and geographic settings. What follows is a kind of statistical average of three names that seem to surface most often.

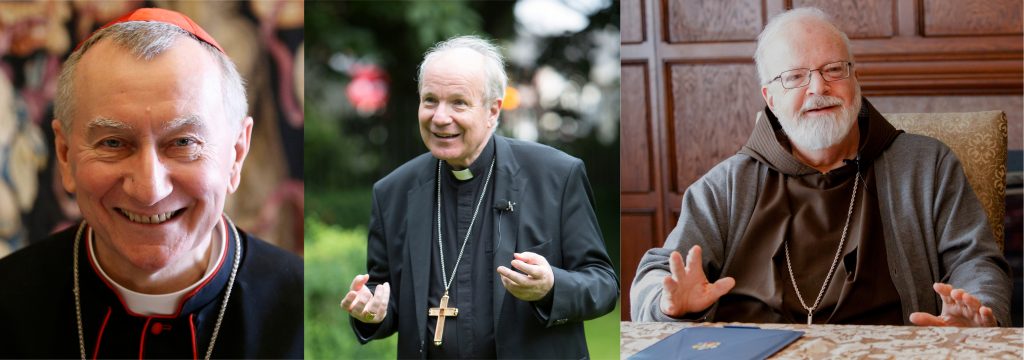

1. Cardinal Pietro Parolin, Italian, 63

Parolin is pretty much everybody’s consistent “safe” pick. He’s in sync with Pope Francis, so he’d represent continuity with this papacy, but he’s also a career Vatican diplomat, making him a good bet for a more cautious and calmer version of the boss.

He’s respected for his deft handling of international affairs and his stable, reassuring leadership, though some wonder if the way he’s ceded management of internal Vatican affairs largely to his subordinates up to now would augur well for finishing the job on Vatican reform.

2. Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, Austrian, 73

A grand irony is that Schönborn’s main problem as a papal candidate right now is that after spending two decades as the dauphin of Ratzinger, potentially making it difficult to attract liberal support, the Austrian scion of a family that’s produced two cardinals and 19 archbishops, bishops, priests and religious sisters so far, he might now have a hard time attracting conservatives because of his backing for Francis, especially on “Amoris Laetitia” (“The Joy of Love”).

Yet precisely that background might allow him to cross traditional divides, and anyway, as a genuine Dominican intellectual, many of his fellow cardinals just think he may be the brightest bulb they’ve got.

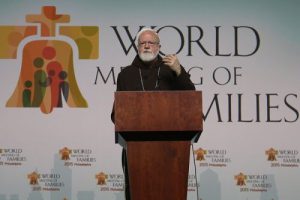

3. Cardinal Sean O’Malley, American, 74

Although O’Malley’s age might appear to be a problem, the last two popes were elected at 78 and 76, respectively, so clearly it’s not a deal-breaker. Otherwise, the American Capuchin has a lot going for him.

Because of his background and languages, he’s not seen as excessively “American.” He’s got a reputation as a leader and reformer on the clerical sexual abuse scandals, and he also has strong appeal to popular Italian sentiment because he reminds them of Padre Pio, the celebrated Capuchin stigmatic and healer.

Further, O’Malley is a good combination of a Francis loyalist who’s nevertheless sensitive to concerns of those a bit disaffected, which could position him to build a two-thirds vote in a conclave.

Beyond those conventional choices, the October 2018 synod also put a couple of other personalities on the radar screed as possible popes, even if neither man is yet a cardinal.

The first is Archbishop Charles Scicluna of Malta, who, despite being remarkably short in physical stature, left a large impression. He’s been the Vatican’s top prosecutor on sex abuse and the pope’s lead man in Chile, but that’s not his only issue. Scicluna generally came off as smart, informed, multilingual, and the real deal as a “reformer.”

The second is Archbishop Anthony Fisher of Sydney, Australia, who turned heads consistently throughout the synod with his articulate, thoughtful, and almost completely nonideological commentary. A Dominican like Schönborn, Fisher, despite being the Australian protégé of Cardinal George Pell, strikes people more for how smart he is than how opinionated.

Scicluna is 59, Fisher 58, so the sky’s the limit for both. Time will tell if the 2018 synod was the turning point for either one, but don’t dismiss the possibility — St. Pope John Paul II, among others, first made his mark on the global Catholic stage in the 1974 Synod on Evangelization in the Modern World, where he was the relator, or chairman.