When I go to a museum, I don’t like to look at a hundred pictures for a short time. I like to look at one picture for a long time.

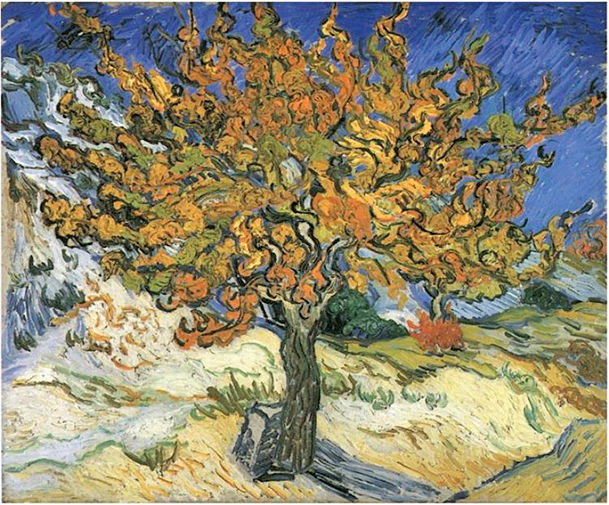

I’ve often visited the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, for example, simply to stand before Vincent van Gogh’s “The Mulberry Tree.”

Van Gogh was notoriously obsessed with color. “The Mulberry Tree” includes olive, sea, pea, agave, cedar, pine and blue-green; chartreuse, ocher, chrome, pale and butter yellow, cobalt, sparrow and forget-me-not blue, taupe and ivory.

The thickly laid paint has an almost incarnate quality. The branches of the mulberry tendril, swirl, quest, seek, reach. Against a Madonna-blue sky, the tree seems almost to be on fire.

The work was completed just five months before van Gogh’s suicide. He was at the mental asylum at St.-Rémy, where he’d committed himself in the spring of 1889 after the infamous ear-cutting incident. In spite of periodic debilitating attacks, possibly from epilepsy, he was incredibly prolific during the year he spent there.

He may have been mentally and emotionally fragile, but van Gogh was clearly in absolute command of his craft. His person was apparently untidy, his studio a volcanic mess, but his purity of heart shines through like the sun in his work.

Van Gogh himself described his brushstrokes in the piece as “firm and interwoven with feeling, like a piece of music played with emotion.”

Van Gogh was a misfit and a lover of Christ from youth. His religious yearnings were central to his work.

Prior to his art career, he considered becoming a pastor and ministered to the coal miners of the Belgian Borinage. In his one surviving sermon, he wrote: “Our life is a pilgrim’s progress. … And the pilgrim goes on, sorrowful but always rejoicing — sorrowful because it is so far off and the road so long; hopeful as he looks up to the eternal city far away, resplendent in the evening glow.”

His subjects were simple, homely: a pair of work boots, a group of peasants sharing a meal of roast potatoes and coffee. Deeply grounded in the Gospels, he painted over thirty works featuring The Sower.

“One does not expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give; rather, one begins to see more clearly that life is only a kind of sowing time, and the harvest is not here,” he wrote in a letter to his art-dealer brother (and sole means of support), Theo.

Many art critics see van Gogh’s religious leanings as a sign, or even the cause of, his insanity. In “Van Gogh,” biographer Frank Elgar writes:

“During the year he remained at the asylum he produced another hundred and fifty pictures, and hundreds of drawings, working as one possessed, interrupted in his labor by three long crises, followed by painful prostrations. He painted ‘Yellow Wheat,’ ‘Starry Night,’ ‘Asylum Grounds in Autumn,’ a few portraits including that of the ‘Chief Superintendent of the Asylum,’ delirious landscapes, surging mountains, whirling suns, cypresses and olive trees twisted by heat. In compensation, rhythm became more intense: whirling arabesques, dismantled forms, perspective fleeing toward the horizon in a desperate riot of lines and colors. What he represented then on his canvases he seems to have seen through a vertigo of the imagination. The fire lit by his hand was communicated to his brain. A feeling of failure overwhelmed him. Could his works be inferior to those of the masters he admired?”

My own impression isn’t of a man beset by fear of failure but of a man on fire with the mysteries of suffering and love. While confined to the hospital at St.-Remy, van Gogh also painted three seldom-mentioned works: “The Pietà,” “The Good Samaritan” and “The Raising of Lazarus.”

In fact, standing before “The Mulberry Tree,” I wonder if van Gogh was inspired by Luke 17:6: “If you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it will obey you.”

As for van Gogh, “Certainly, I do not believe that my type of insanity could be persecution mania, because my mind, in a state of excitement, always concerns itself with infinity and with everlasting life.”

Perhaps that longing for infinity is what draws me, again and again, to the paintings, the letters, the arc of van Gogh’s short, tormented life. Perhaps his ability to channel his suffering into his work is why I tend to go to see “The Mulberry Tree” when I’m in emotional pain myself.

Van Gogh carried a life-long torch for his beautiful cousin Kee. His father and his uncle, Kee’s father — clergymen both — were violently opposed to the union. Kee herself did not return his love. He was too volatile, they all agreed, and too poor.

He had long ago become disillusioned with all institutional churches. “That does not keep me from having a terrible need of — shall say the world — religion. Then I go out at night to paint the stars.”

Norton Simon Museum of Art411 W. Colorado Blvd.Pasadena, CA 91105(626) 449-6840www.nortonsimon.org

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.