On the feast of the Immaculate Conception in 1932, Dorothy Day visited the National Shrine and prayed that “some way would be opened for me to work for the poor and the oppressed.”

When she returned from the National Shrine to her apartment in New York, the French peasant-intellectual Peter Maurin was waiting on her doorstep, and on May 1, 1933, the lay Catholic Worker movement was born: first a newspaper, then a soup kitchen, then the first “house of hospitality” from which a worldwide lay movement would eventually blossom.

Dorothy’s checkered past — the Bohemian nightlife, the flirtation with Communism, the abortion, the 1927 conversion, the common-law marriage — were behind her. She’d given up Forster Batterham, the resolutely atheistic love of her life, because of his refusal to sanction the baptism of the child they’d conceived together, Tamar. The separation was wrenching, the hardest thing that she would ever do, she later said,.

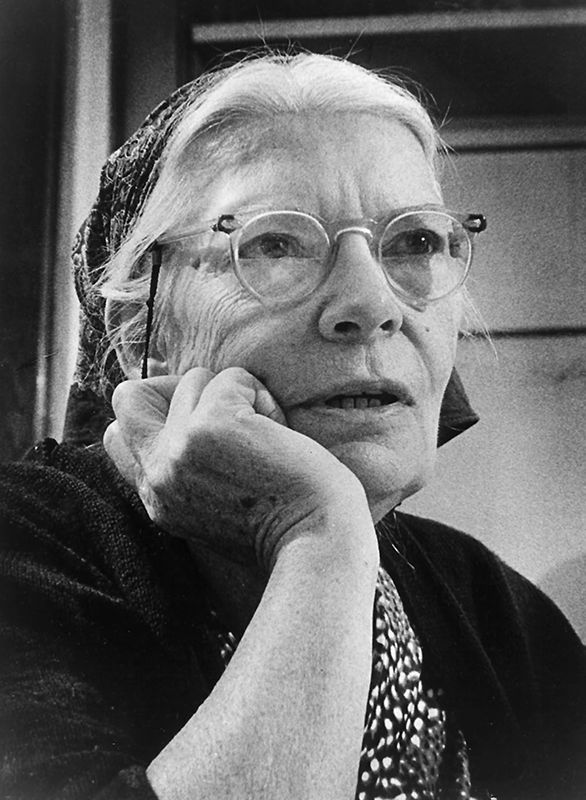

If Dorothy said it was hard, you know it had to be. Notoriously unwilling to suffer fools gladly, she said, “Don’t call me saint!” But if the saint “is the person who wills the one thing,” as Kierkegaard opined, she came awfully close.

Dorothy’s diaries span the years from 1934, a little under a year after the Catholic Worker began, to nine days before her death in 1980.

“We see her traveling to Cuba on the eve of the missile crisis, fasting for peace in Rome during the Second Vatican Council … and standing in solidarity with young men burning their draft cards,” writes editor Robert Ellsberg in his terrific introduction.

Peter Maurin’s role was to “enunciate principles”; Dorothy’s was to implement them. By May of 1935, the circulation of “The Catholic Worker” newspaper had already reached an astonishing 100,000. By 1941, there were already over 30 independent but affiliated Catholic Worker communities in the U.S., Canada and the UK.

“A crowded, confused day with a great desire on my part to write on love and the strange things that happen to you in growing in the love of God,” Dorothy wrote on Sept. 20, 1953. The love of God was the one thing she willed, and she willed it through poverty, celibacy, obedience, labor strikes, jail time, illness, and struggles with the Church.

For all her radicalism, she was as observant as any medieval nun. For all her activity, she was at heart a mystic. She built her life on a bedrock of daily devotions: the Divine Office, rosaries, vigils, prayer, fasts and, always, the Mass.

“Time only for the prayer of Jesus — always time for that. Waiting traveling, at any time, in any place, that murmur of the heart. My Lord and my God, my Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

As of 1944, she owned only three pairs of stockings (“heavy cotton, grey, tan and one brown wool”), all of which had come to her “from the cancerous poor, entering a hospital to die.”

But the real poverty consisted in the fact that no matter how much she did, it was never quite enough to stem the tide of drunks and crazy people, the shell-shocked, the quarrelsome and argumentative who streamed through the house and whom she made it her life’s mission to love and serve.

“The prevalent complaint … [is] … ‘you are never here!’”

If community was a cross, Dorothy made clear, it was at the same time an enormous blessing. If she was “poor,” she reminded herself, she was also rich. She trained herself to look not at the faults in others, but rather at the faults in herself.

“Physical and spiritual senses need to be ‘mortified,’ subdued, disciplined,” she observed. That was at the age of 78.

She kept up a voluminous correspondence, hand-writing up to 10 letters a day (that she didn’t keep carbon copies she considered a small act of humility). She was an avid reader. She loved music: Bach, Brahms, opera.

But first and foremost, Dorothy was a writer. Year after year, she got the newspaper to press, wrote her column, “On Pilgrimage,” and published books: “The Long Loneliness,” “Loaves and Fishes” and several others.

“I am not interested in politics or elections,” she observed.

Instead, she lectured, attended conferences, traveled around the country by bus to visit the burgeoning number of sister houses. In July 1973, she accepted an invitation to speak at Joan Baez’s Institute for the Study of Nonviolence in Palo Alto, and while there, also picketed with the UFW. It would be her final arrest.

“The true anarchist asks nothing for himself, he is self-disciplined, self-denying, accepting the Cross, without asking sympathy, without complaint.” Her words could have been a caption for the famous photo of that day in Delano: mouth set, eyes fierce, staring down an armed policeman.

On Nov. 29, 1980, Dorothy Day died in her bed at Maryhouse, the Catholic Worker shelter for homeless women on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She was surrounded by the people she had loved and served and who, at the last, served her.

For the follower of Christ, that’s insurance. That service, come full circle, is healthcare.