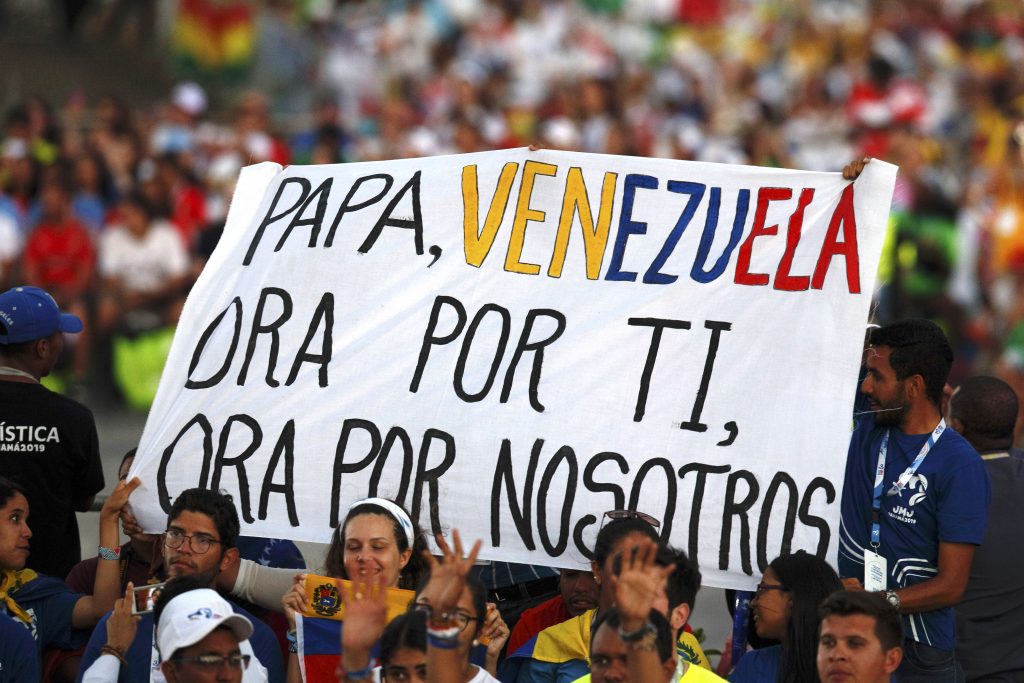

ROME — As Pope Francis was en route to Panama to participate in a Vatican-sponsored youth festival, a political and economic crisis in Venezuela continued to unravel, with the president of the National Assembly, following the country’s constitution, being sworn into the presidency, openly challenging the incumbent Nicolas Maduro.

The international community soon took sides: Russia, China, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) sided with the successor of Hugo Chavez, with the UAE agreeing to buy 15 tons of gold with cash after President Donald Trump announced economic sanctions on Venezuela.

On the other side of the street, the United States, along with most of Latin America and the European Union to varying degrees, backed the challenger Juan Guaido. At the beginning, the EU simply asked Maduro to call for elections, but has since hardened its position.

After two decades of “Chavismo,” the political ideology based on the ideas of the late Hugo Chavez, Venezuela has gone from being one of the wealthiest countries in the region, mostly due to its oil reserves, to one of the poorest.

The annual inflation rate at the end of 2018 was a staggering 80,000 percent. People had to wait in line for days to buy bread, and hospitals were going on social media to report they didn’t have gauze or flu vaccine, much less treatments for cancer patients.

In 2017 people lost an average of 18 pounds due to lack of food, and the year before, one person was killed every 12 to 18 minutes due to unchecked violence.

Hence, many ask, why doesn’t Francis openly challenge Maduro? Why doesn’t the Holy See break diplomatic ties? And a personal favorite, found on Twitter and shared by those with no memory at all: “What would St. Pope John Paul II have done?”

In fact, John Paul was the first pope to shake hands with Cuba’s Fidel Castro, Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner, and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. In 1983, he went to Haiti and shook hands with “Baby Doc” Duvalier and then visited the Philippines while it was ruled by dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

In the words of a famous American cardinal, Castro is the only dictator who survived a visit by the Polish pope. His stance against Communism and any form of dictatorship were the stuff of legend, and to this day, many credit John Paul with playing a key role in the fall of the Soviet Union and the Berlin Wall.

Yet despite his condemnation of the tragic situations, the Holy See had, or wanted to have, diplomatic ties with each one of these countries, regardless of the dictators in power. Was this duplicity, or a classic case of keeping your friends close, your enemies closer?

Behind the scenes in Haiti, John Paul didn’t just stage a meet-and-greet with Duvalier, he also encouraged the local episcopacy to be brave in standing up to the regime.

The late archbishop of Manila, Cardinal Jaime Sin, the informal leader of the Filipino People Power Revolution that swept Marco from power, was on record saying that he had been inspired above all by John Paul and the Solidarity movement.

In other words, sometimes holding your fire in public is the price of being able to exercise real influence in private.

Despite having been invited, especially early on in his pontificate, Francis has never set foot in Venezuela. Instead, he offered the Vatican’s willingness to mediate in dialogue efforts after the bloodshed of 2017. He’s called for a “peaceful” solution for the crisis, and last week said that the solution had to respect the “human rights of all.”

Juan Guaido speaks during his first public appearance since declaring himself the legitimate Venezuelan president during a news conference in Caracas Jan. 25. (CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE/CARLOS GARCIA RAWLINS, REUTERS)

In fact, Francis may not need to engage in a verbal crossfire with the government given the outspokenness of the Venezuelan bishops, who are openly calling for Maduro to step aside.

The bishops have long been against the president, reelected last May under questionable circumstances, as every opposition leader who could have defeated him was in prison. Maduro tried to tell the Venezuelan people that the bishops and the pope were at odds, but no one in Venezuela believed him.

To prove him wrong, the pontiff welcomed the prelates in Rome soon after the comments were made.

In addition, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Parolin, sent a private letter to Maduro in 2016 demanding him to release political prisoners, to open a humanitarian corridor in Venezuela and reestablish the electoral calendar. Maduro’s response? A televised rant saying that he had proof in his hands of Parolin’s secret “maneuver to implode the dialogue.”

The Italian cardinal was hand-picked by Francis to occupy his position, and was literally lifted from his position as Vatican representative in Venezuela. Maduro and Parolin, in other words, know each other well.

In addition, the “sostituto” (“substitute”) often referred to as the second most important person in the secretariat, comes from this Latin American country, Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra.

When Francis calls for a “dialogic” and “peaceful” solution, he’s upholding the Vatican’s long-standing tradition of forging diplomatic ties with every country and every government, and the reason is simple. As the world’s strongest softest power, the Holy See cannot threaten economic sanctions, invade a country, or impose a blockade.

Yet it can run soup kitchens through Caritas and other Catholic charities that today are the only thing keeping many Venezuelans alive.

It can summon bishops to Rome, or Panama, to give them the chance to smuggle medicine back into the country. It can look the other way when the bishops ask priests to join political protests — and when they do so themselves — even though the Church hierarchy, technically, is supposed to stay out of politics.

Furthermore, the Vatican gave the bishops a greenlight to call Maduro’s government “illegitimate,” and the bishops were consulted by the Holy See when the time came to decide if a representative should be sent to Maduro’s swearing-in (the decision was “yes.”)

Talking to the diplomatic corps accredited to the Holy See earlier this year, Francis said peaceful institutional solutions can be found to the ongoing political, social, and economic crisis, and that “the Holy See has no intention of interfering in the life of states; it seeks instead to be an attentive listener, sensitive to issues involving humanity, out of a sincere and humble desire to be at the service of every man and woman.”

When it comes to Venezuela, that seems to mean not caving in to a government many perceive to be dictatorial, but giving the bishops the leeway to speak freely while, behind closed doors, Vatican diplomats guarantee that Caritas is allowed to function and that seven bishops’ conferences from Latin America work together to aid the hundreds of thousands who’ve fled Venezuela in recent years.

Inés San Martín is an Argentinian journalist and Rome Bureau Chief for Crux. She is a frequent contributor to the print edition of Angelus and, through an exclusive content-sharing arrangement with Crux, provides news and analysis to AngelusNews.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!