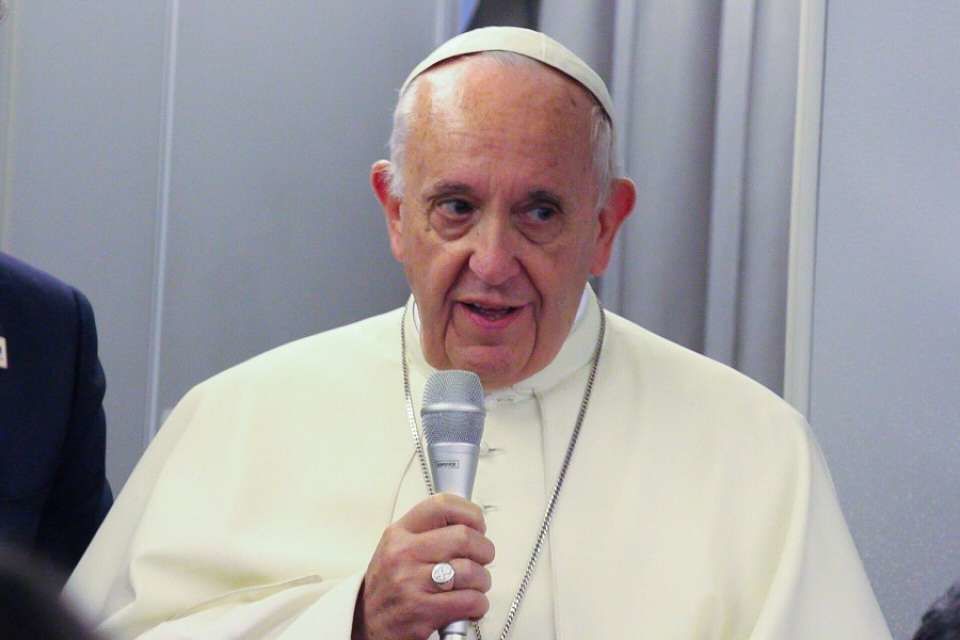

On his return flight from Bangladesh to Rome, Pope Francis offered journalists an insight into his communication strategy, saying that when it comes to a sensitive topic, at times he prefers to hold his tongue publicly so that his message gets across, but be more open in private conversations.

“For me, the most important thing is that the message arrives and in order to do this I try to say things, step by step, and listen to the answers, so that the message may arrive,” the Pope said on his Dec. 2 flight from Dhaka to Rome.

He was returning from a Nov. 27-Dec. 2 visit to south Asia, which took him to both Burma and Bangladesh.

A major underlying theme of the trip was crisis surrounding the Rohingya, a largely Muslim ethnic group who reside in Burma’s Rakhine State, who have faced levels of state-sanctioned violence so drastic that the United Nations has called their plight “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Of particular concern was whether or not Pope Francis would use the term “Rohingya” in his public speeches, because despite widespread use of the word in the international community, the term is controversial within Burma. The Burmese government refuses to use the term, and considers the Rohingya to be illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. They have been denied citizenship since Burma gained independence in 1948.

Given the delicate political situation, Pope Francis had been advised by local Church leaders in Burma to avoid using the word during official speeches, which he did. However, after meeting with a group of 18 Rohingya Muslims at an interreligious encounter in Bangladesh, he decided to drop the phrase publicly, breaking with his previous protocol.

During an hour-long press conference with journalists on board the flight, which consisted of 12 questions focused primarily on the visit, Francis was asked if he regretted not using the word “Rohingya” publicly while in Burma.

In his answer, the Pope noted that he has used the term publicly several times in different audiences and speeches, so “it was already known what I thought about this thing and what I had said.”

However, he said the question made him reflect on “how I try to communicate,” and the most important goal is always to ensure that his message gets across.

Using the image of a teenager as an everyday example, he said that if they are in a crisis, they “say what they think by throwing the door in the face of the other...and the message doesn’t arrive. It closes.”

When it came to using the word “Rohingya,” Francis said he realized that if he used it in the official speeches, “I would have thrown the door in a face,” implying that the term would have prevented Burmese officials from hearing his message.

Instead, he said he chose to describe the situation and the lack of human rights, and to advocate for inclusion and citizenship in public. In private conversations, however, the Pope said he allowed himself to “go beyond.”

While in Burma, also called Myanmar, the Pope met privately with officials, including General Min Aung Hlaing, the military’s commander-in-chief and a powerful political figure in the nation.

“I was very, very satisfied with the talks that I was able to have,” he said, explaining that while he didn't have “the pleasure throwing the door in face, publicly, a denouncement,” he was able to have “the satisfaction of dialoguing and letting the other speak and to say my part.”

In the end, Pope Francis said his message got across, and that “this is very important in communications, the concern that the message will arrive.”

The Pope told journalists that he didn’t know whether he would have the opportunity to meet with Rohingya representatives while in Bangladesh. He thanked the Bangladeshi government for allowing the Rohingya to join him for the Dec. 1 interreligious encounter, saying the country is a good example of what it means to welcome and to have open doors.

Many of the 18 Rohingya present at the meeting didn't know they would meet him either, Francis said, explaining that they were taken from the crowd and told to get in line to greet him, but not to say anything.

“I didn’t like that,” he said. And when the organizers tried to usher them off stage right away, “I got mad and a chewed them out a bit,” he said, confessing that “I'm a sinner.”

After hearing each of them share their stories, Francis said he was moved and wanted to say something to them spontaneously, so he offered a brief prayer in which he asked for forgiveness on behalf of all who harmed them.

“In that moment I cried. I tried not to let it be seen. They cried too,” he said, noting that the other religious leaders who came up to greet them were also moved.

By doing things in this way, Pope Francis said he felt that “the message had arrived. Part was planned, but the majority came out spontaneously.”