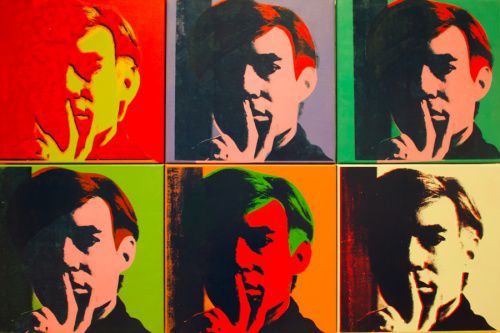

Chances are you've heard of the phrase “15 minutes of fame.” And you've probably seen the neon-colored canvases of Campbell soup cans or Marilyn Monroe's face — even if you don't know the artist behind them. For those who've never studied Andy Warhol and his prolific body of work, they've still most likely encountered it in many of the pop icons of the late 20th Century. But while Warhol may be known best for the his visionary depiction of fame and popular culture, his art can also be understood as iconic — in another, much more literal, way. Why? Because he was an ardently practicing Byzantine Catholic, say those close to the artist and his work. In fact, they say, Warhol's art is actually best understood through the lens of faith and iconography. However, these same voices warn that both the art world and Catholics alike have tended to oversimplify or ignore aspects of the man that, to this day, refuses to be categorized. “Warhol's a very complicated person and whatever angle we really try to take to his art, we can take one angle to come from but it's always going to be incomplete if we don’t take another angle as well,” said art historian Dr. James Romaine. Romaine, who also serves as president of the international Association of Scholars of Christianity in the History of Art, said that the widespread read on Warhol's work — that it's largely a critique of consumerism — actually isn't at odds with a more religious interpretation of his art. “The more popular description of Warhol's work being concerned with popular culture, commodity culture, I think that's all true,” he told CNA. “And I don't see it as being inconsistent in any way with what we’ve already talked about with sacred art,” he said. “I see these same sides of Warhol's work as enhancing each other.” So who was Andy Warhol? Or should we say — who was Andrew Warhola? A Humble Beginning The artist who would become Andy Warhol was born as Andrew Warhola on Aug. 6, 1928, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His parents, Ondrej and Julia Warhola immigrated to the United States in 1914 and 1921, respectively, from what is today Slovakia. They raised their family of three sons in the Byzantine Catholic Church. Andrew was often sick as a child, and spent much time bedridden, collecting pictures and drawing. His father passed away in an accident when he was just 13. After high school, Warhol studied commercial art at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, later renamed Carnegie Mellon University. Following graduation in 1949, he moved to New York City, where he worked in magazine illustration and advertising, and also started signing his last name “Warhol,” rather than “Warhola.” His mother joined him in New York in 1952, where she lived with her son until her death in 1972. Throughout the 50s and 60s, Warhol gained attention for his painting techniques, and later photography, film, installments and multi-media exhibitions. The late 1960s also brought Warhol close to death when he was shot near the entrance to his Factory workspace. After the shooting, Warhol continued to work prodigiously, co-founding Interview Magazine, designing record covers, producing television programs, and continuing to paint both commissioned works and his own artistic series. He passed away suddenly on Feb. 22, 1987, during a routine gallbladder surgery. In the nearly 30 years since the artist's death, his art has left a lasting impact on society not only due to the vast popularity of his work, but the major themes he wrestles with and explores. “Warhol has been celebrated by critics and art historians for his ability to probe some of the most challenging themes of modern society: identity politics, celebrity, death, religion, desire, and the capitalist machine,” said Jessica Beck, assistant curator for The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. “From the very beginning of his career, Warhol had a particularly keen understanding of the power and weight of images,” she told CNA, “and he was able to produce a body of work that remains extremely relevant and accessible to contemporary audiences.” But while a small amount of religious work has been explored by scholars such as Lynne Cooke and Jane D. Dillenberger, largely these themes — “relative to the Pop paintings of Campbell's Soup and Coca-Cola or the celebrity portraits” — are “somewhat under-researched,” Beck said. An Abiding Faith For Warhol, faith was an integral part of family life and a daily practice — and both of these remained important to the artist until his death, according to his nephew, Donald Warhola. While many assume he was non-religious, Andy Warhol “was far from an atheist,” Warhola told CNA. “He was a practicing Byzantine Catholic, and actually attended a Roman church later in his life.” This dedication to the faith was a critical part of Andy's daily life. Warhola recalled that his uncle would visit his neighborhood Roman Catholic parish in New York City “and pray every day.” After Warhol passed away, the priest approached the Warhola family at his memorial “and said to us that he was going to miss his daily talks with Uncle Andy.” From among Warhol's personal collection displayed in the Warhol Museum after his death are religious items such as a sculpture of the Sacred Heart. But for the Warhola family, the Catholic faith was more than daily practice, and was a key part of their family life and source of personal strength. “Sunday was meant for worship,” Donald said. He added that his grandparents — Andy Warhol's parents — raised their sons to place Church and visiting with family first on Sundays. Even when Andy Warhol moved from Pittsburgh to New York City in order pursue his art career, faith remained an important familial touchstone. “Always he would ask if I went to Church because it was a Sunday,” Warhola said of his phone calls with his uncle. “He was very religious: it was a very big part of his upbringing as well as mine.” “I know Uncle Andy was the character who had that through his upbringing and I know that he depended on God for strength.” Donald Warhola also got to know his uncle in a working environment was well, installing a computer system for Andy for several months before his death at Andy Warhol Enterprises in New York. At work, Donald describes his uncle as “quiet” but also a hard worker and fair employer, bringing their family emphasis on hard work into the workplace. “He wasn't too much different, but it was interesting to see Uncle Andy in that element and his work element as opposed to the more casual, laid back visiting at his place.” These “really basic and old school” lessons from his uncle stuck with the then-24-year-old Warhola. Donald recounted meeting someone in New York who wanted to design the young worker a “fancy business card” to use for future job searches. Uncle Andy told him “a fancy business card won't get you work,” but promised that if he did a good job at his work, he would write his nephew a good referral and help find him a good job. “The funny thing is that after that, on jobs that I took, it seems that I never got business cards,” he laughed. “Subconsciously something landed in my mind to avoid business cards.” Other colleagues of Warhol also noticed the artist’s Catholic faith and devotion, such as Bob Colacello. He relayed that Warhol's faith “was not an act,” after attending Mass with Warhol and visiting the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe, according to Jane Dillenberger's work in “The Religious Art of Andy Warhol.” Warhol's diaries also provide a record of his internal religious life, documenting weekly Mass attendance, volunteer work at a parish soup kitchen, and his experience of meeting and shaking hands with then-pontiff Saint John Paul II in 1980. He also recorded his anxiety being surrounded by the “scary” crowds in St. Peter's Square waiting for the Pope, although he fought off his nervousness in order to sign autographs for several nuns. Warhol additionally wrote that he screamed after the assassination attempt on John Paul II in 1981. Art as Iconography Just as faith played an important place in Warhol's life so too did it surface as an important topic in his art. He worked on several explicitly religious pieces, including appropriations and reinventions of Raphael's “Madonna” and da Vinci's “Last Supper.” A camouflage version of the latter, Romaine observed, can be interpreted as “bringing back the halo on and over Christ’s head,” which was removed in da Vinci's original humanist painting. For Romaine, however, Warhol's religious themes run into all his work — even that thought of as non-religious. “If I had to describe Andy Warhol’s work in just one or two sentences, I would describe it as the world seen not as it is, but the world seen as it might be transformed by grace.” Romaine explained that in the Eastern Catholic churches, religious icons play a vital role in worship and spiritual life. As opposed to altar pieces or other sacred art in the Western Church, “the icon is more of a specific presence of the saints there with an icon,” he said. “The sacred image is not directly bringing the Virgin Mary into the Church, whereas with the icon, the presence of the saints is believed to be more directly there.” He said that by viewing Warhol's work — particularly his paintings — with an eye towards iconography, “I see all of Warhol's work as potentially sacred.” As an example, Romaine pointed to the now-iconic printing of the Campbell soup can. “Soup cans are disposable food,” he said. “But the way Warhol depicts them, he removed them from a time and place context in which they're disposable, into a timeless realm in which they're almost like icons.” The soup can also had a ritual tie to Warhol's life. He recalled Warhol's brother mentioning “Andy eating Campbell’s soup every day, having a soup and sandwich every day, and the importance of religious imagery in their home” — including over the kitchen table where Warhol ate his soup. Similarly, Romaine said, people are presented in a glorified, redemptive manner in Warhol's paintings. The artist finished the now-classic screen print of Marilyn Monroe shortly after the actress's sudden death after a tumultuous life. Yet, Warhol's work “doesn't depict her as a tragic figure,” he remarked, “not that we shouldn't have sympathy for her.” “He celebrates her. He sees her in a way as being, in fact, beautiful.” Warhol also portrays Elizabeth Taylor, another actress dealing with scandal at the time of the painting. “He's depicting those women at critical moments in their lives. Warhol depicts her as kind of redeeming her through his imagery.” “If you're familiar with the Christian concept of the transfiguration...Christ appears to his disciples not as he is, but in a glorified way. He's not just this guy walking around, but he's glorified. Romaine commented that in the way the soup can or Marilyn Monroe, or Liz Taylor are presented, it reminds him of the Transfiguration, where Christ is presented to the disciples in the fullness of His glory. Likewise, in these images, Romaine said, “I kind of see Warhol seeing the whole world as potentially glorified.” This glorification of the popular is one of the markers of Warhol's art, Romaine noted. “His work is so much connected with the lowest of the low commodity culture makes the transfiguration that takes place in his work, all the more miraculous, all the more important.” “If he's depicting the Virgin Mary as sacred, it's sort of obvious already, but if you're depicting the soup can as sacred, it’s really transformative.” Daniel Warhola agreed that, while “we never had a conversation on that topic,” it makes sense to him that Eastern iconography would have an influence on his uncle's artwork. “Perhaps I'm jaded because I grew up in the same environment but to me it seems obvious: the Byzantine Catholic Church is all about Heaven on Earth and you are stimulating the various senses and your eyes with the various icons and beautiful stained glass windows, and you know that the smell of incense and the sounds,” he stated. Among the important sensory parts of the liturgy, he continued, are “the icons, sort of the celebrities of religion.” “To me it’s very obvious that the way he presented his pop art, you take these iconic figures out of society, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and make them iconic in the way he presented them.” A Complicated Man However, while Andrew Warhola was a man of faith and his Catholic understanding of the world did make its way into his art, Andy Warhol also dealt intimately with themes such as fame, popular culture, mass production and sexuality — that would become nearly ubiquitous in the 30 years after his death. “I’ve just always thought Uncle Andy was able to predict what was going to be popular ahead of his time,” Donald Warhola said. He called his uncle's work “progressive” in that it “was ahead of his time.” “From a standpoint of when I look at the body of work that he did in the 60s and 70s, even 80s, he was always touching on what was going to be popular in the future.” Warhola pointed to his uncle's prediction that “in the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes” and art projects such as the filming of ordinary people living their lives. “I think if you look at reality TV, some people, not everyone, are intrigued by just watching someone live their life,” he said, adding that while Warhol was exploring the medium of what has become reality TV in the 60s and 70s, at the time.“it was not popular and it was controversial and not understood.” “It was almost like he was looking for future trends in his art.” Some of the trends Warhol explored extensively were that of sexuality and sexual orientation, which he revisited throughout his professional career. “There's no question that Andy Warhol was homosexual,” Romaine said. Indeed, several scholars, such as Dillenberger, have documented that he was open about his attractions since the 1950s, and several of his art projects explore his fascination with voyeurism and the sexually explicit. However, in interviews late in his life Warhol also proclaimed that he was “still a virgin” and eschewed participation in the acts he depicted. “After twenty-five,” Warhol told Scott Cohen in a 1980 interview, “you should look, but never touch.” “I don't know exactly what that means for him, but because of his religious upbringing but even more so because of his intense shyness he wrestled with any sort of a sexual relationship,” Romaine commented. “His art then becomes a means by which he can realize some of the sexual longing that he has that he’s not able to realize in relationships.” These tensions between faith and sexuality, introversion and explicitness wrapped themselves around some of Warhol’s work with identity, Romaine said, bringing up the series “Ladies and Gentlemen,” portraits of drag queens and transsexual attendees at New York clubs. “It’s a sort of play on the perception and the answer is 'yes' — it’s both a lady and a gentleman: there's this slippage of identity.” The “and” in the title, Romaine continued, is “insightful” and important to understanding the point Warhol explored in the piece. “It's sort of the one image that portrays being a drag queen as a sort of divided identity,” Romaine continued, and in putting both parts of the “lady” and the “gentleman” portrayed together in one series he's attempting to resolve “a conflict.” In looking back, Warhol's nephew also sees the question of identity as one that concerned his uncle personally and that Andy Warhol explored in his work. “I've always thought,” Warhola told CNA, “that there’s two personas: there's the Andrew Warhola persona that I, for the most part, got to know, and the Andy Warhol persona.” “And I think that the Andy Warhol persona that almost gave my uncle the permission to do the things that Andrew Warhola would not feel comfortable doing or being.” “It's almost like an actor who goes out and plays a role, then they're able to act out maybe different aspects of their personality or life that they’re not totally comfortable with as their own individual,” Donald said. “That’s just my own interpretation: I just think that maybe Uncle Andy experienced that.” Warhola also suggested that perhaps some of the character Andy Warhol became and the work the artist produced was itself a type of creation. This persona, Warhola added, grew and changed with public expectations and “wherever people took that, he was okay with it.” “Almost like he could see himself as a work of art, and let you create the narrative,” his nephew said. “‘I'll put out the information out there and you can create the narrative as you see fit. I'll be what you almost want me to be,' in some ways.” There may be another reason for allowing for a tension between his public and personae, Warhola added: business. “Also my uncle saw that controversy sells, and that if you’re getting attention, it doesn’t matter if it’s positive or negative — that's what you need to be out there.” Art as Reconciliation Towards what would be the the end of his life, however, Andrew Warhola shifted focus from feeding the expectations others had for Andy Warhol. “He wasn’t painting necessarily for other people, but was more painting from his soul, and he did a lot of various religious works,” Donald Warhola noted, bringing up “The Last Supper” paintings and the “Heaven and Hell” series. “The themes kind of changed — at least what caught my attention changed,” he said. “It seemed like again he wasn’t worried so much about ‘gee, what can I paint that everyone’s going to like?’ It was more like he was trying to make statements with his artwork.” Warhola added that while earlier in his uncle’s career, the artist was concerned with staying “totally relevant” to avoid fading from popularity like other contemporary artists, later on Warhol eventually stopped orienting his artwork around other's expectations. “At a certain point, he just figured 'I'm going to paint what I want to paint.'” “After that it was more subtle, and then I think he became more profound closer to his death.” Romaine suggested, however, that the resolution of identity and other themes in Warhol's work can be seen throughout his career — and underlying that resolution is a distinctly Catholic theme. He directed attention to the resolution of male and female identities in “Ladies and Gentlemen” and other paintings, brought together with the understanding of iconography he sees in Warhol’s corpus. The resolution, Romaine said, is “this striving for grace in a broken world.” Another example of an artistic imagining that not only elevates the base, but resolves conflict and redeems a subject, Romaine said, are the prints of Marilyn Monroe. “Marilyn Monroe at the time he paints her is a picture of identity conflict,” he said, “And in his image, I think he tries to pull her together.” “This desire in his depictions of Marilyn, to reconcile these different Marilyns with each other I think projects from his own desire in his own life of having so many internal conflicts: of being on the one hand successful, and on the other feeling like a failure, on being on the one hand desirous of relationships and being unable to realize them,” Romaine said. “These conflicts that exist at the very core of Warhol's being, then drive him to create an art in which these conflicts are reconciled. Conflicts that can’t be reconciled in life can be reconciled in a work of art.”