We’ve all seen the videos on YouTube and online: A stone-faced reporter on a college campus or a wisecracking “man on the street” interviewer stops random people and asks them simple questions about American politics and American history.

It’s a litany of what otherwise educated people don’t know about their own country. Who is the Vice President, how many branches represent the Federal Government, how many U.S. Senators are in the Senate? If you’re three for three, congratulations.

As we hover around the Independence Day part of the summer marketing season, it would do us all well to remember the Founding Fathers — incredible men who risked everything to bring the American experiment into existence. It had its flaws, and no one knew that more than they did. That is why the Declaration of Independence has a stated goal “a more perfect union,” not a perfect one.

The early part of July is also a time when news media will debate whether the Founding Fathers were overtly believing Christians or just nebulous deists. I’ll leave that debate to others, because there is a Founding Father who makes that question very easy to answer, even if the man himself is relatively unknown. He has fallen through one of those historical wormholes and not gotten the attention he deserves.

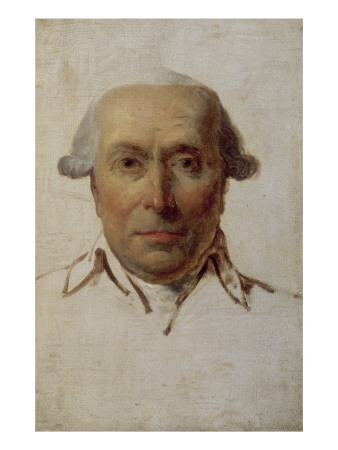

That has changed though, with the publication by the Mentoris Project of “America’s Forgotten Founding Father,” by author Rosanne Welch. Welch has written a novelized historical document about the life of Filippo Mazzei — sounds like an all-American name to me…and it should, because Filippo Mazzei’s story is in its essence an all-American story.

He lived from 1730 to 1816, in the wheelhouse of world-turning-upside moments like the Enlightenment, the American Revolution and the French Revolution. Trained in medicine, his European career saw him challenge the overreach of the Inquisition, become a confidant of the Sultan Mahmud I of the Ottoman Empire and, while staying in England, his growing expertise as a merchant had his paths cross with Benjamin Franklin, who was there seeking to sell his newly invented pot belly stove. His meeting of Franklin would be a harbinger of things to come.

In what can only be described as divine intervention, Mazzei’s travels, which included royal palaces in Italy and elsewhere throughout Europe, finally guided him to the New World, where his knowledge of agriculture and wine-making, combined with the inviting soil of Virginia, had him putting down roots just three years before Jefferson would write the Declaration of Independence.

His American adventure makes him sound like a latter-day Forest Gump. Mazzei’s life intersected with the biggest names in Virginia and the men who would soon change the world with an experiment that continues today. He was neighbor first and soon friend and confidant to Thomas Jefferson. He corresponded regularly with John Adams, and talked farming techniques with George Washington. He spoke at least four languages and maybe as many as six.

And to top it all off, Filippo Mazzei was a faithful Catholic in a British Colony where that fact was a novel reality.

He was present in the House of Burgesses when Patrick Henry declared, “Give me liberty or give me death.” He counseled Jefferson about the evils of slavery and, though there is no way to know if his view had a large impact on Jefferson, it is important to note that in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson, though a slaveholder himself, wrote a scathing commentary on the practice of chattel slavery, which was eventually removed for the final draft to keep all 13 Colonies committed to the Revolution.

Mazzei traveled back to Europe, using his connections to help secure the future of his adoptive country and suffered personally and financially for his efforts.

Even after the Revolution, Mazzei had many other adventures described in this book that this space cannot do justice. Foreign intrigue notwithstanding, “America’s Forgotten Founding Father” is a book whose timing could not be better on a domestic level.

Although men like Jefferson, Washington and Adams represented a homogeneous group of white, English, Protestant, landed gentry, they all welcomed a new immigrant from a non-English speaking, predominantly Catholic country. And Filippo Mazzei showed that a Catholic could, in good conscience, be fully integrated into that great American experiment at its birth, and help christen it with a little holy water.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.