SAN SALVADOR — Violence has escalated over the past few weeks in El Salvador. Gang hitmen — sicarios —recently killed two soldiers who were guarding a bus station that is part of the recently opened Metropolitan System of Transport of Grand San Salvador (SITRAMSS).

Similar attacks had taken place before, but in a show of force, this ambush was executed in a crowded public area as if it were a military operation. The attackers executed their plan with impressive coordination and teamwork. According to some witnesses, they employed a man posing as a beggar to distract their targets.

The next day, the U.S. Department of State issued a new travel warning alerting U.S. citizens that “crime and violence level in El Salvador remain high.”

So far this year, dozens of army personnel and police officers, men and women, have been slaughtered by gangs, known here as maras, in a number of ambushes and assaults. Some of them were attacked while commuting to their homes.

In addition, a large number of spouses or relatives of police officers and soldiers have been killed in cold blood solely because of their relationship to law enforcement or military personnel.

This history would be incomplete if we fail to include the deaths of almost 200 young gang members at the hands of police.

The state of violence in this country has reached a point where things could spiral out of control. Ill equipped police officers, desperate under constant fire, can easily succumb to the temptation to commit human rights abuses.

The independent digital newspaper El Faro investigated an official report of a gunfight in a rural outpost of La Libertad between gang members and a special police unit in which eight gang members were killed, including a 16-year-old girl. Photos released by the National Civilian Police (PNC) show the bodies of the dead gang members lying next to guns and automatic rifles. However, eyewitness accounts and forensic evidence suggest that they were actually executed at close range, according to El Faro.

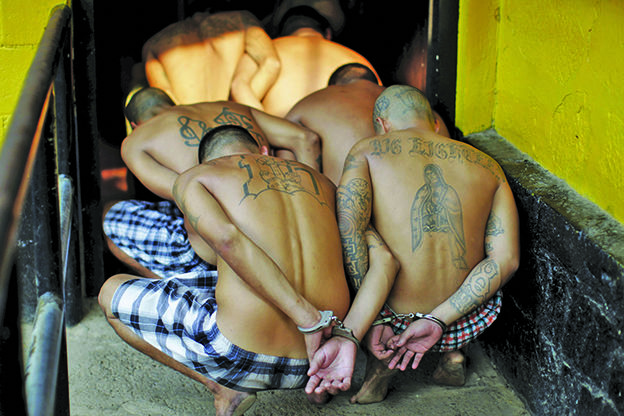

Another media account describes police officers kicking and punching scores of handcuffed suspects inside a police station following the murder of two soldiers at the SITRAMSS bus station. Ironically, none of the suspects was charged for lack of evidence.

These questionable police practices do not help the administration of President Salvador Sánchez Cerén to reduce crime. Since the former guerrilla commander came to power a year ago, he has been subjected to unrelenting attacks by the right wing opposition and the powerful media they own.

Those criticisms have become high pitched and virulent since violence took a turn for the worse this year. Government detractors have suggested that El Salvador is a failed state and some have even suggested that the country is in a “state of war.”

But nothing could be further from the truth. What we have in El Salvador is an eruption of social violence fed by rampant poverty. Chronic unemployment and lack of social and cultural options provide a constant stream of young people flowing into criminal gangs.

Hundreds of thousands of guns are in the hands of civilians, and disputes for a parking space ending in a killing are not rare events. The economic agenda of the last 20 years is based on Salvadorans migrating to the U.S.

The billions in money remittances sent back home by those migrants has enriched the elite beyond their wildest dreams. The result of all this is the growth of a criminal underclass that extorts and kills.

For this economic elite, it is more convenient to propagate the idea that the country is immersed in a war, rather than admitting the existence of poverty and its consequences.

Confronted with an explosion of social violence, the government has to avoid the voices that call for a military response to public safety. Militarization will not resolve the underlying economic problems nor improve public safety, and as the conflict escalates and becomes more desperate, the risk is that in attempting to confront gang members the conflict will spiral into an unending cycle of violence.

El Salvador needs a strong police department, which is well trained and has good salaries, but additionally it must confront poverty directly in order to achieve an active and involved citizenship, and a tolerant, fair and peaceful society.

Roger Lindo, a regular contributor to Vida Nueva, the archdiocese’sSpanish-language newspaper, writes from San Salvador.