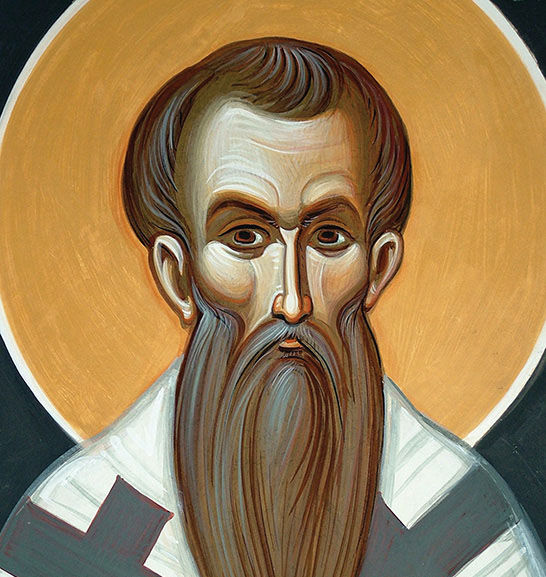

It was not the first time Basil had infuriated the governor.

Modestus favored the heresy known as Arianism, which denied that Jesus was truly God. And, as governor in Caesarea, Modestus knew he had the power of the emperor on his side.

He tried to win Basil through threats and bribes and he failed consistently. Basil had no fear of confiscation because he owned nothing. When Modestus threatened him with exile, Basil responded that, as a Catholic, he belonged to no place and would feel at home anywhere. “The whole earth is God’s,” he said.

Enraged, the governor said, “Never have I been spoken to with so much liberty!”

To which Basil replied: “Maybe that’s because you’ve never met a bishop.”

What was a bishop in the fourth century, when Basil served in Caesarea? The same as a bishop in the first century or the 21st — he was a successor of the apostles, the shepherd of a particular church entrusted to him.

As long as there has been a Church of Jesus Christ, there have been bishops. When Jesus had ascended to heaven, the apostles immediately gathered to fill the vacancy left by Judas’ suicide.

St. Peter said: “May another take his office” (Acts 1:20). The Greek word translated as “office” is episkopen, which is the root of the English “bishop.”

For those who succeed to the office of the apostles, the Church has always used the term bishop.

Indeed, the apostles themselves appointed bishops whenever they founded a church. Saint Paul opens his letter to the Philippians with a greeting to the bishops and deacons there.

His letters to Timothy and Titus (the so-called pastoral epistles) are largely instruction manuals on how to be a bishop. The Apostle describes the bishop’s work as “a noble task” (1 Timothy 3:1).

A bishop is “God’s steward … a lover of goodness, temperate, just, holy and self-controlled, holding fast to the true message as taught so that he will be able both to exhort with sound doctrine and to refute opponents” (Titus 1:7-9).

Note that the bishop is a “steward,” a caretaker. He has no authority or power of his own. What he has belongs rightly to God. He has received it as a gift through the rite of ordination. St. Paul urged Timothy “to rekindle the gift of God that is within you through the laying on of my hands” (2 Timothy 1:6).

What began in the New Testament is confirmed in every generation afterward. Wherever Christianity spread, there were bishops.

St. Clement of Rome — who was himself a disciple of the apostles Peter and Paul — explained the reason for the Church’s tradition of succession. He wrote:

“Our apostles knew, through our Lord Jesus Christ, that there would be strife on account of the office of bishop. For this reason, therefore, since they had been given a perfect foreknowledge of this, they appointed successors … and afterwards gave instructions that when those men should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed them in their ministry.”

He wrote those words perhaps as early as 67 AD and surely no later than 97. Already the principle was firmly in place.

Writing in the year 107 AD, St. Ignatius of Antioch assumed that every local church has its own bishop who serves as God’s vicar. Ignatius told the Christians of Magnesia:

“Take care to do all things in harmony with God, with the bishop presiding in the place of God.”

In those first generations after the apostles, the bishop’s place was clear. He was the Church’s public face and objective point of reference. As Ignatius told the faithful in Smyrna:

“Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be; as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful to baptize or give communion without the consent of the bishop. On the other hand, whatever has his approval is pleasing to God.”

As the public face of Christianity, the bishops were always vulnerable. To be a Christian was illegal in the Roman world from the middle of the first century to the beginning of the fourth.

Most Christians could pass unnoticed in a crowd and survive the passing purges; but not the bishops. They were well known and so many of them suffered for the faith and many died as martyrs.

Some Roman persecutions particularly targeted only clergy and primarily bishops. The first five saints mentioned in our First Eucharistic Prayer were bishops of Rome, and the next name mentioned is St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage. To don the vestments of a bishop was to wear a target.

We can see, then, where St. Basil got the cheek to talk back to the governor Modestus. The job of bishop demanded fortitude in those days, as it still does today.

St. Irenaeus of Lyons was himself a bishop, a martyr and the first systematic theologian. He lived in the second century and had been baptized by the martyr-bishop Polycarp, who had himself been a disciple of the Apostle John.

For him the office of bishop was the mark of a true Christian congregation. In his day already there were many who claimed to be Christian teachers and some of them preached a strange Gospel.

But Irenaeus counseled Christians to follow only Catholic bishops — those who could trace their lineage back to the apostles.

A hundred years later the Church historian Eusebius (also a bishop) staked the same claim. In his chronicles, he said, he would consider as authentic churches only those who trace “lines of succession from the holy apostles.”

He wanted to demonstrate that the Catholic faith was “not modern or strange, but … primitive, unique and true,” and the doctrine of the bishops gave him that assurance.

The bishops were teachers. They were authorities. They were judges. But all of these roles were secondary. Their primary role in the Church was fatherly. They were fathers, who — like all earthly fathers — shared in God’s own fatherhood.

From the earliest times, many Christians kept the custom of addressing their bishop with the endearing name small children use for their father. In Egypt and in Rome, it was “papa.”

Over time that word morphed into a technical term, pope, with a distinct religious meaning. But the best of those who held the office never forgot their deepest identity. As St. John XXIII said: “Papa is really only Papa.”

Every bishop is called to be a good father, and “really” that is all. They are charged to teach, rule, sanctify, protect, defend and provide for God’s family on earth.

They have to lead. They have to take risks. They have to model the best behavior, because everyone — pagans and Christians alike — expect the bishops to embody the ideals of Jesus Christ.

If the Gospel is true, it should shine in the bishop’s life. When a bishop fails, those who scorn Christianity feel that they are vindicated in their hatred.

Some have failed spectacularly, but relatively few — remarkably few.

If that surprises you, maybe that’s because you’ve never met a bishop.

We should pray always for the bishops God has given us. The Mass teaches us how: “Lord, remember your Church … make us grow in love, together with our bishops.”