Veteran religion reporter Peter Steinfels has published an in-depth article questioning both the motivation and the methodology of the August Pennsylvania grand jury report, which chronicled seven decades of abuse within the state’s six Catholic dioceses and led to the resignation of one of the nation’s top Catholic cardinals.

The nearly 11,000 word essay, “The PA Grand-Jury Report: Not What It Seems,” released on Thursday in Commonweal magazine, concludes that the report is “grossly misleading, irresponsible, inaccurate, and unjust.”

“It is contradicted by material found in the report itself - if one actually reads it carefully. It is contradicted by testimony submitted to the grand jury but ignored - and, I believe, by evidence that the grand jury never pursued,” Steinfels continued.

Steinfels, who served as religion reporter for the New York Times for a decade, scrutinized the 1,356 report pages and is critical of what is both in the report and what is left excluded.

“What precisely, I asked myself, did the Pennsylvania report tell us that was new?” Steinfels states is his guiding question for the missive.

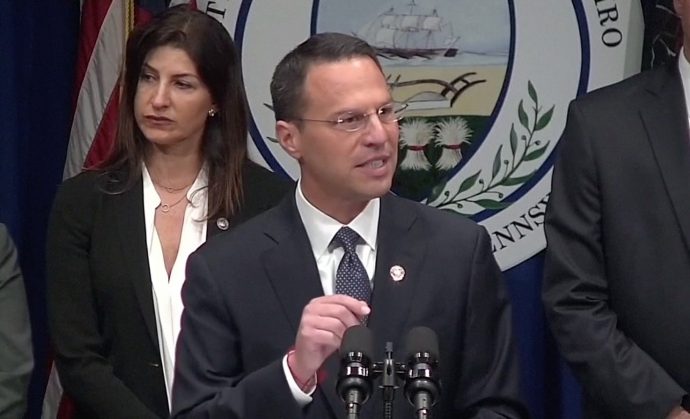

While grand juries are the first step used by prosecutors to garner an indictment that could eventually lead to a trial, he notes - using the words of jurist Stanley Fuld - that an investigative report, as released by Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro in August, is “at once an accusation and a final condemnation, and, emanating from a judicial body occupying a position of respect and importance in the community, its potential for harm is incalculable.”

Steinfels observes that the individuals and actions listed in the grand jury report can only be defended or challenged after the report has been published, which is often too late for the court of public opinion, such as the case of that of Cardinal Donald Wuerl, whose handling of abuse cases as bishop of Pittsburgh in the 1980s and 1990s would lead to his resignation as archbishop of Washington last October.

Wuerl had sought to clarify some of the reports findings prior to publication but was not granted an opportunity to do so.

While Steinfels laments the “stomach-churning” accounts of abuse chronicled in the report, he is critical of the structure in which it is presented, what he describes as the sensational descriptions used in the report’s introduction which shaped the media narrative of its release, and the lack of information included to recount the Church’s response to these cases.

“There are no efforts to discern statistical patterns in the ages of abusers, the rates of abuse over time, the actions of law enforcement, or changes in responses by church officials,” he writes.

“Nor are there comparisons to other institutions. One naturally wonders what a seventy-to-eighty-year scrutiny of sex abuse in public schools or juvenile penal facilities would find.”

Steinfels, who notes that he has his own list of grievances against the Church hierarchy and is not writing defensively on their behalf, claims that the report’s failings cripples its ability to offer serious recommendations that could prove beneficial to all concerned parties.

“I believe that the grand jury could have reached precise, accurate, informing, and hard-hitting findings about what different church leaders did and did not do, what was regularly done in some places and some decades and not in others,” he argues.

“It could have presented ample grounds for at least three of its four rather unoriginal recommendations without engaging in broad-brush denunciations. It could have confirmed and corrected much that we think we know about the causes and prevention of the sexual abuse of young people.”

The findings of the Pennsylvania report and its related attention have led more than a dozen other states to announce their own investigation into the Catholic Church’s handling of sexual abuse, as well as hints of a potential federal review.

Steinfels believes that the evidence in the Pennsylvania report, if looked at in an unbiased manner, suggests that the policies instituted in 2002 by the U.S. Church, known as the Dallas Charter, have worked, even if improvement is needed.

“The Dallas Charter has worked,” he declares. “Not worked perfectly, not without need for regular improvements and constant watchfulness. But worked. Justified alarm and demands for accountability at instances of either deliberate noncompliance or bureaucratic incompetence should not be wrenched into an ill-founded pretense that, fundamentally, nothing has changed.”

While the new frontier for reform is now focused on standards and protocol for bishop accountability, Steinfels concludes his analysis by arguing that in advance of next month’s high stakes Vatican summit on sex abuse, the U.S. Church should have confidence that its ongoing reform has nevertheless worked.

“The Dallas Charter is decidedly not a recipe that can simply be transferred to any society or culture or legal and governmental situation around the globe,” he writes.

“But American bishops should go to the Vatican’s February summit meeting on sexual abuse confident that the measures they’ve already adopted have made an important difference,” he concludes.