A week later, Kris Brough’s head was still spinning.

The principal of Our Lady of Lourdes School in Northridge had just come back from Finland with 11 local Catholic school principals to observe the Nordic nation’s acclaimed education system in late March.

The group visited primary, middle and secondary schools, met with administrators, teachers and students, and attended lectures at the University of Tampere, where many teachers are trained.

“We were overwhelmed by seeing the Finnish educational system in action,” he wrote in a letter to his school’s parents. “So much of it is transferable, and a great deal of what we observed is rooted in the distinct culture of Finland.”

One of those transferable lessons is the basic value of trust, which the principal says is a foundation for successful learning. Parents trusting teachers, teachers trusting students as well as students trusting teachers.

On many occasions, the principals observed children, from the first grade up, doing lessons alone on school campuses, which Finnish educators believe fosters creativity.

“Part of that trust I think comes from the fact that teaching is a rather highly regarded profession in Finland,” Brough said in an interview with Angelus News. “There are just three teaching universities and they only accept 10 percent of applicants. Here in the states, parents are so likely to question the teacher — their credentials, their motivations. And that’s pervasive.

“But in smaller Finland trust pervades everything. And for students it leads to increased independence and increased creativity because the kids are able to identify their best learning situation. And that may be outside the classroom in the library or gym — alone or in small groups. We saw this at all grade levels. So I think they are a little bit more self-directed than our students might be.”

Classroom trust

Three fellow principals Angelus News interviewed readily agreed.

At the one high school they visited in Finland, the administrators walked into a classroom with a student making a presentation — with no teacher present. The other students were busy taking notes and doing a peer evaluation of the presenter. Downstairs in another visited classroom, it was the same. In the library there were no adults, just a small group working on math problems.

“That level of independence taught to children began at an early age,” said Patricia Holmquist, principal of Our Lady of Refuge School in Long Beach. “The little ones are responsible to get their own clothing and boots on and off. They dished up their own lunch in the cafeteria and bused their own tables. And walked themselves to school.”

Just how safe Finland was also stood out for the principal of All Souls School in Alhambra. Carrie Ann Fuller watched three little girls with backpacks heading home from school. On a cell phone, one was calling her parents: “I’m heading home.”

“Even though the society is so safe, that was still surprising to see that scene,” she recalled.

“What was surprising was the independence of the children.”

That independence applied to teachers as well, according to Erika Avila, principal of St. Vincent School in Los Angeles.

“When we asked administrators, ‘Do you check lesson plans of the teachers?’ they looked at us very bizarrely. Like saying, ‘Why? They are doing what they need to do.’ So administrators in Finland spend more of their time looking at their budget, finding funds to help their school out and just enjoying the good teaching that’s happening in the classrooms.

“It was amazing,” Avila added, “because we spend a lot of time here in the U.S. hovering over our teachers, checking up on them, which isn’t very trusting.”

From left: Ryan Halverson, Ryan Bushore, Kris Brough, and Rick Billups record observations after visiting classrooms.

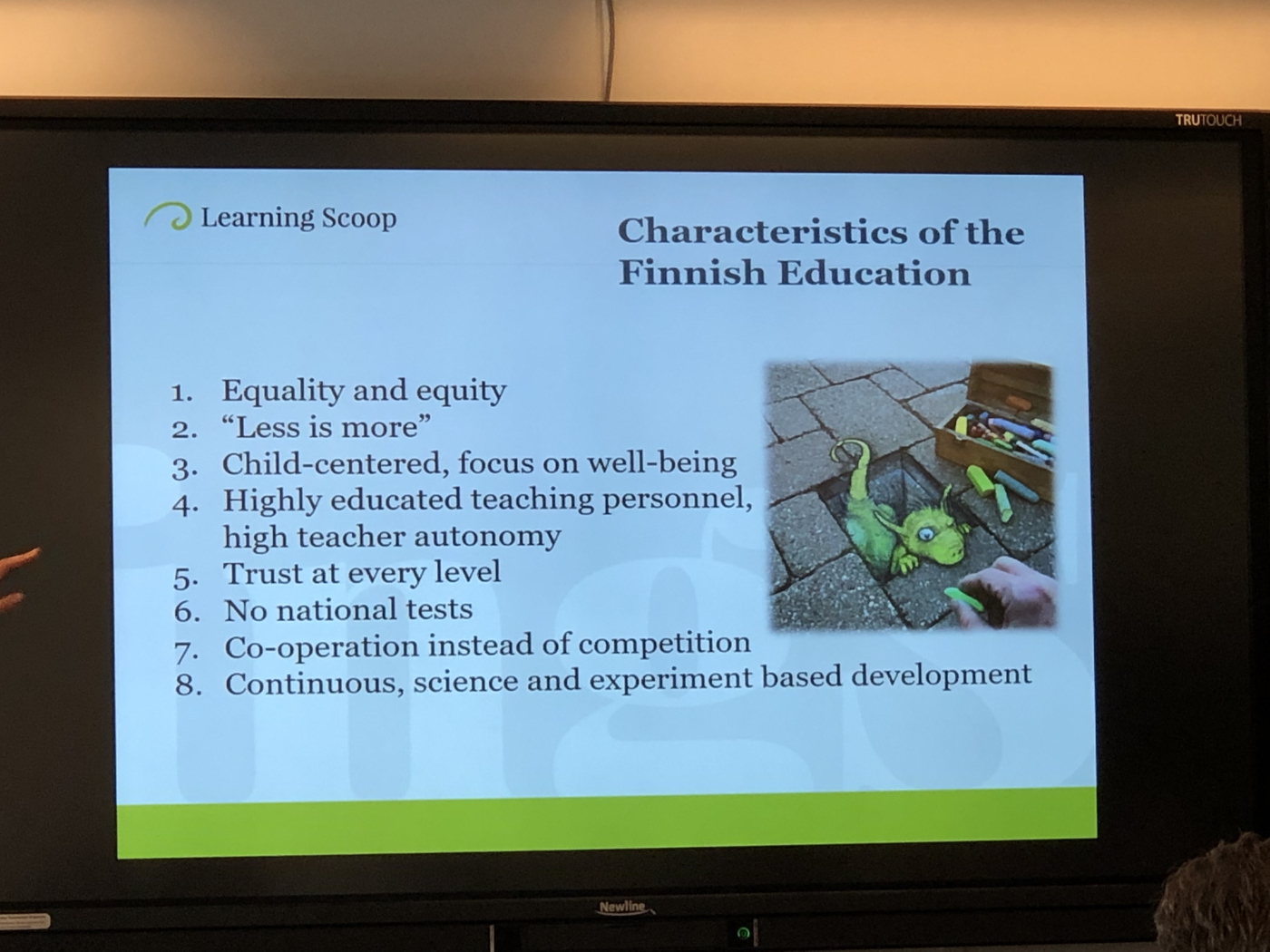

‘Less is more’

Another element of Finnish education, which has been rated among the top among industrialized nations, is a basic logic of “less is more.” Less testing means less stress on students cramming for exams and more focused on learning, agreed the principals.

The school day, at least for middle school and high school, is shorter. Depending on what class they have first, school for Finnish students might start at 10 a.m. and be over by 1 p.m. But it was less testing and less homework that stood out for the California visitors

“The teachers we talked to stressed that students don’t have much homework or none,” said Holmquist of Our Lady of Refuge.

“But when they do have homework, it’s very purposeful. There’s intentionality behind it. And it’s not doing repetitive things, like going through one to 25 math problems. It would be very targeted, like maybe five homework problems to show they’ve mastered the lesson. And then they move on.”

Another big difference is how Finns look on vocational training versus higher education: Both are valued the same. And every student takes classes in wood and metal shops, arts and crafts, home economics, and even sewing, life skills that can serve students well later in life no matter their profession or occupation.

And then there’s “brain breaks” every so often to stimulate learning. Sometimes students go outside, even in the winter, to take a brief hiatus from all that learning and just get some fresh air.

Transferable lessons

So are any of these best practices of Finnish education transferable to local Catholic schools here?

Brough, the principal of Our Lady of Lourdes School who helped organize the trip, believes some definitely are.

“Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles are autonomous within a small network compared to public schools,” he pointed out.

“We have the flexibility to actually experiment and in real time try to implement some of these things. The goal for us now is to stop talking about Finland and start celebrating what we’re doing, so that in the future we can say, ‘We tried this and it’s working.’ Efforts that will support some system change.”

After a moment, the educator added: “We want to commit our schools to taking different tracks to try to implement these innovations, then some of us who went to Finland will really adopt the notion of ‘less is more’ or ‘brain breaks.’ And then compare those students with others who didn’t have these breaks to see who did better. Are younger students with more play time really more creative?

“And if more breaks and play time means better students, later on point to our colleagues in the archdiocese and say, ‘We saw this in action over in Finland and now we’ve tried it and it’s working.’ So our goal is to sustain engagement with these lessons that we’ve picked up and to support each other in implementing them, and then share the successes more widely with other Catholic schools.”

Fuller said her teachers at All Souls have already been doing some lessons the principals took away from Finland, educational elements like building independence in children, caring for the environment and doing these “brain breaks,” especially in primary grades.

“Also making sure that lessons are interactive,” she said. “Mini-lessons with the younger children should only be 15 to 20 minutes. After, they’re moving to the carpet for “wiggle breaks.”

“But we need to make sure ‘brain breaks’ and interactive learning are also happening in the upper grades,” stressed the principal.

“We’re trying to prepare our students to make sustainable life choices, to trust their teachers and to work together. Those were things I noticed in the Finnish schools that we’re trying to implement. Seeing these things firsthand happening in Finland made me realize we’re on the right track. And now I want to emphasize them even more.”

Note: The other local principals who went on the weeklong trip to Finland were Ryan Halverson of St. Cyril of Jerusalem School in Encino, Ryan Bushore of St. Pascal Baylon School in Thousand Oaks, Nicole Johnson of St. Aloysius Gonzaga School in Los Angeles, Allison Kargas of St. Anthony School in Long Beach, Beate Nguyen of St. Augustine School in Culver City, Raquel Shin of St. Patrick School in North Hollywood, Fidela Suelto of Holy Family School in Glendale, and Rick Billups of St. Bernard High School in Playa del Rey.

R.W. Dellinger is the feature editor of Angelus.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!