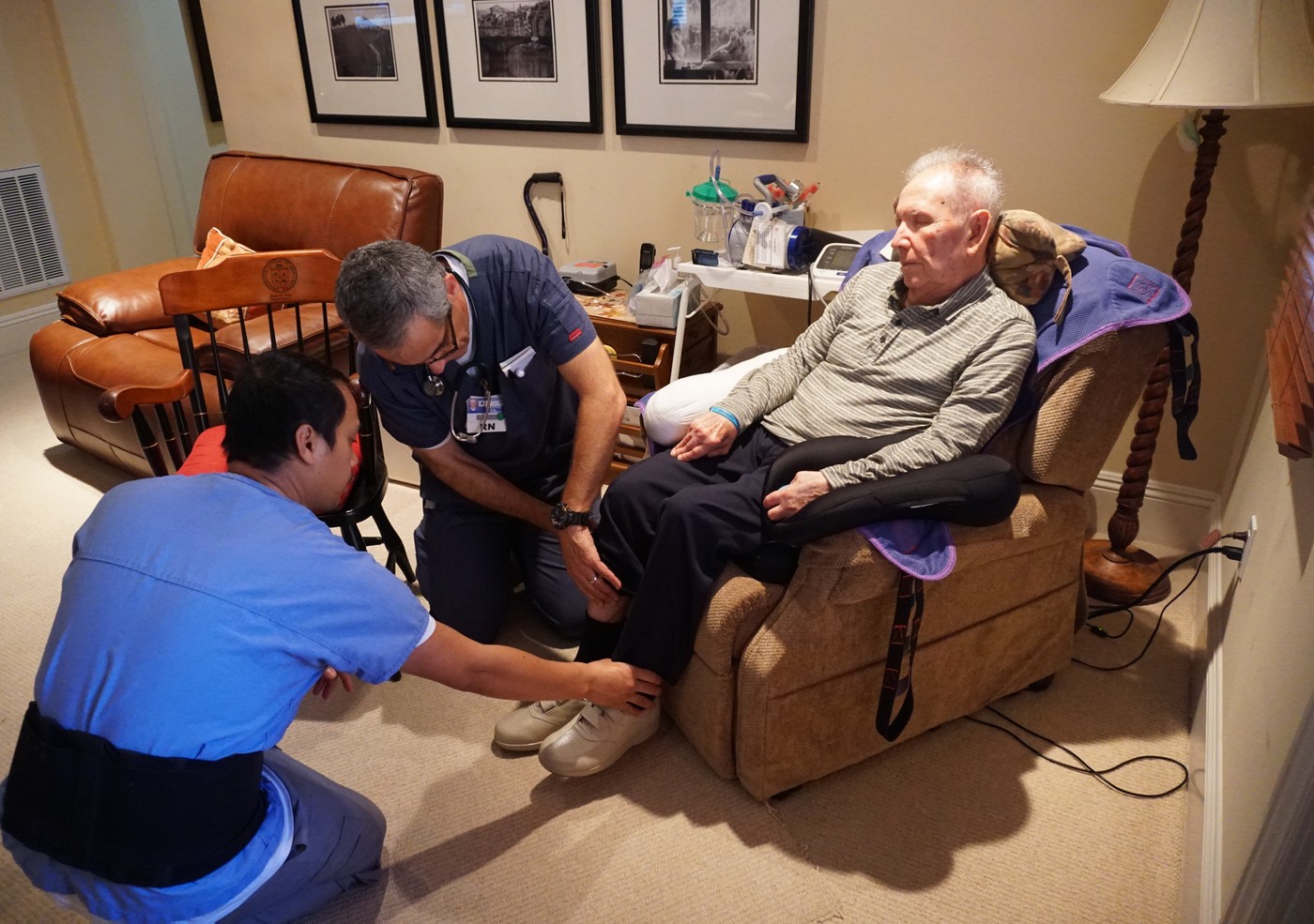

Standing in a closet-sized room in an Encino apartment on a recent Thursday morning, Tom Doyle was bent over his 72-year-old dying patient trying to get a blood pressure reading.

The hospice nurse wasn’t having much luck. Ronald Lavery was unconscious, eyes closed, and head turned to the left, lying under a green sheet that only covered half his chest. Standing nearby was Lavery’s wife of 42 years, Gwendolyn, or “Gwen,” donning a khaki floppy hat pulled down over her forehead.

Doyle was wearing a short-sleeve medical top over matching pants. His glasses slid down a bit as he worked. His hair was short and gray, but he still looked younger than his 59 years.

The cramped, stuffy room was filled with noise coming from the oxygen concentration machine, which sounded like an old lawnmower. A tube connected it to the tracheotomy in the patient’s neck.

Gwen showed Doyle a notebook filled with meticulous notes full of written-down times, numbers, and comments.

“So this is what happened, Tom, overnight,” she said. “These are all the stats right here.”

“Blood pressure kind of low,” muttered the nurse as he studied the pages.

Gwen nodded: “His pulse is getting weak, right?”

“It’s still kind of bad, but not as bad as it has been, because the blood pressure is getting low.”

Then the 71-year-old woman ticked off the medications she had been giving her husband overnight and early this morning.

“That’s fine,” he answered.

Thirteen years ago, Ronald had a massive stroke, leaving his left side paralyzed. The episode was followed by a number of medical problems. Lately, he had been in the hospital, where he was on a ventilator with a feeding tube up his nose. But he yanked out the feeding tube, telling his wife he didn’t want any more extraordinary measures to prolong his life.

When no facility would take him after his stay in the hospital because of his tracheostomy, Gwen reluctantly brought her husband home to die. But she didn’t really know how to provide the intense medical care he needed. And she remembered the doctors at the hospital saying something about hospice care.

“I had no idea,” she told Angelus News during an interview at her home. “I thought hospice was a place to go to, because they said to me he refused all treatment, and he won’t allow them to put another feeding tube in his stomach. But he’d had enough. He’s in pain. So I thought, ‘How am I going to take care of him?’ ”

Enter Providence TrinityCare Hospice, a service of the Catholic not-for-profit Providence health care network. Founded in 1977, the program offers end-of-life hospice care for patients and their families or other caretakers.

Today it’s grown to five clinical teams with a staff of more than 180 professionals in Southern California working in hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities — and in cases like the Lavery’s, the patient’s own home.

In his past life, Doyle was a geologist, working on environmental investigations of soil and groundwater contamination. While working in Wyoming, he broke a leg from slipping on ice, resulting in a hiatus from his on-the-go lifestyle while recovering at his home in Colorado.

During that time, he recalled mostly thinking about one thing: Was he really making a difference in others’ lives or mostly just focusing on himself and his family?

That period marked a turning point in his life.

One day while reading the “Denver Catholic,” the local archdiocesan newspaper, the then-38-year-old came across a call for volunteers for a local hospice run by the Archdiocese of Denver. “The moment I saw it, I was like ‘That’s it! That’s what I’m going to do,’ ” he remembered. “I just had this feeling, even though I didn’t really know hospice at that point.”

Doyle began as a volunteer, but grew so concerned by the way some older persons in nursing homes were treated that he became an ombudsman on behalf of residents. Later, he went back to college, becoming a registered nurse thanks to an accelerated program at California State University Northridge.

Today, the 59-year-old has seven years of hospice work under his belt, including the last 5 1/2 at Providence TrinityCare doing outreach with a team that includes a social worker, a chaplain, other nurses and on-call doctors working mainly in the San Fernando Valley.

“Everything that we do is focused on the comfort of the patient,” explained Doyle.

“Usually, you can’t totally eliminate pain. That would require total sedation, giving the patient enough medication that the person is sleeping all the time. And most patients don’t want that. They want the pain managed, and they get to decide what level of pain is acceptable to them.”

Doyle said an important part of his job is working with relatives on determining how much pain medication a patient actually needs. Too much medication can make it hard to communicate with their loved ones.

“Sometimes we have to coach family members on not making the patient suffer for their own wishes,” he explained, adding, “This is hard for everybody: for patients, for families.”

Doyle said that anxiety or agitation can accompany physical pain of dying persons. And just being short of breath can trigger anxiety, which can then lead to a “feedback loop,” making the shortness of breath even worse. Constipation and nausea are among the symptoms brought on by painkillers that hospice nurses look for.

When they see a home situation that’s not balanced and under control, hospice nurses at Providence TrinityCare can contact on-call doctors to get their advice on increasing the dose of a medication or ordering new ones.

Nurse case managers like Doyle only need to see patients once a week if their condition is pretty stable. But twice a week is more common, and daily visits are made when symptoms are changing rapidly or the patient — like Ronald in Encino — is getting closer to death.

It’s called “continuous care,” with LVNs (licensed vocational nurses) staying with the dying patient all day and night.

But how does a case manager or nurse determine if an unconscious patient or one who can’t speak is really suffering?

“We look for things like a furrowed brow, a grimace on the face as an indicator of pain,” said Doyle.

“The same for restless movements. And the respiration rate. If somebody’s breathing more than 20 times a minute, that’s our trigger to think, ‘Is this due to pain?’ So even if somebody is not responsive and not really conscious, there are signs that we watch for as indicators of pain.”

When the former geologist was asked why he hasn’t burned out working with the dying and their families on a daily basis, he took a moment before responding.

“Again, we just see such amazing displays of love of people taking care of their family members,” he said finally.

“If I can help be a guide through a really rough time and answer questions and just provide support, it’s a great feeling. And, yeah, it’s a difficult time and sometimes we’re there at the time that our patients die. But just to provide the support for the family members is very rewarding.”

Hours after Gwen told Angelus News she was “leaving it in God’s hands,” Ronald passed away at home, his wife of more than four decades by his side. Though she knew the end was near, she had nothing for gratitude to the hospice nurses.

“They are like guardian angels,” she said. “Without them, this would be unbearable.”