The slightly built young Honduran man sat in a chair next to his 7-year-old daughter, who smiled shyly at the stranger asking them to remember their recent separation at the border.

Looking barely more than a child himself, the father’s eyes welled with tears, which he promptly swallowed with a look of determination.

“I don’t want to be rude,” he said, glancing at his daughter. “But I don’t feel comfortable talking about that right now.”

The little girl is now going to school in Los Angeles and the father was attending a group consultation with an attorney from Esperanza Legal Services, a legal nonprofit, to sign up for representation.

He is already working odd jobs to make ends meet, and they both are receiving help from social workers as well as gift cards for food, toiletries, and clothes.

But the trauma that the family has gone through is evident in the father’s reaction, and it presents a challenge even for the organizations that are working to help them.

“We are still trying to get the trust factor in,” said Moises Carrillo, director of Intra-Agency Programs at Catholic Charities of Los Angeles. “They are afraid. If you call them they ask: ‘How did you get my information?’ We have to gain their trust so we can provide them with social and legal services.”

The man and his daughter are one of about 50 reunited families who arrived in the Los Angeles area from Texas over the past few weeks and are being helped by programs belonging to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, including Catholic Charities, Esperanza and Angel’s Flight.

An estimated 3,000 families were swept up at the border this summer as part of a “zero tolerance” immigration policy that criminally prosecuted the adults and sent the children to detention centers thousands of miles away.

After an outcry and court interventions prompted the Trump administration to reunite the families and stop deportations, many were released to sponsors all over the country.

Relatives or friends have opened their homes for these families to live in while they go through immigration or federal court. The process may include another chance to apply for asylum if the first one was rejected at the border. But they still need help with resources and, more importantly, attorneys to fight their cases.

Patricia Ortiz, program director for the Esperanza Immigrant Rights Project, explained that even after being reunited, the majority of the families are going through deportation proceedings.

“As soon as they are referred to us we do an intake and sign them up for representation if they agree,” said Ortiz. “The first thing we do is request a change of venue to make sure their cases are changed to the Los Angeles area and their new addresses.”

Most of them were released with the clothes on their backs, said the attorney.

“That’s why we have to work with our partners in Angel’s Flight, where they do the case management; they need hygiene items, groceries, etc. If they joined family here, they represent an extra cost for the family, or issues with the landlords, etc. They try to help and coordinate all of that,” she explained.

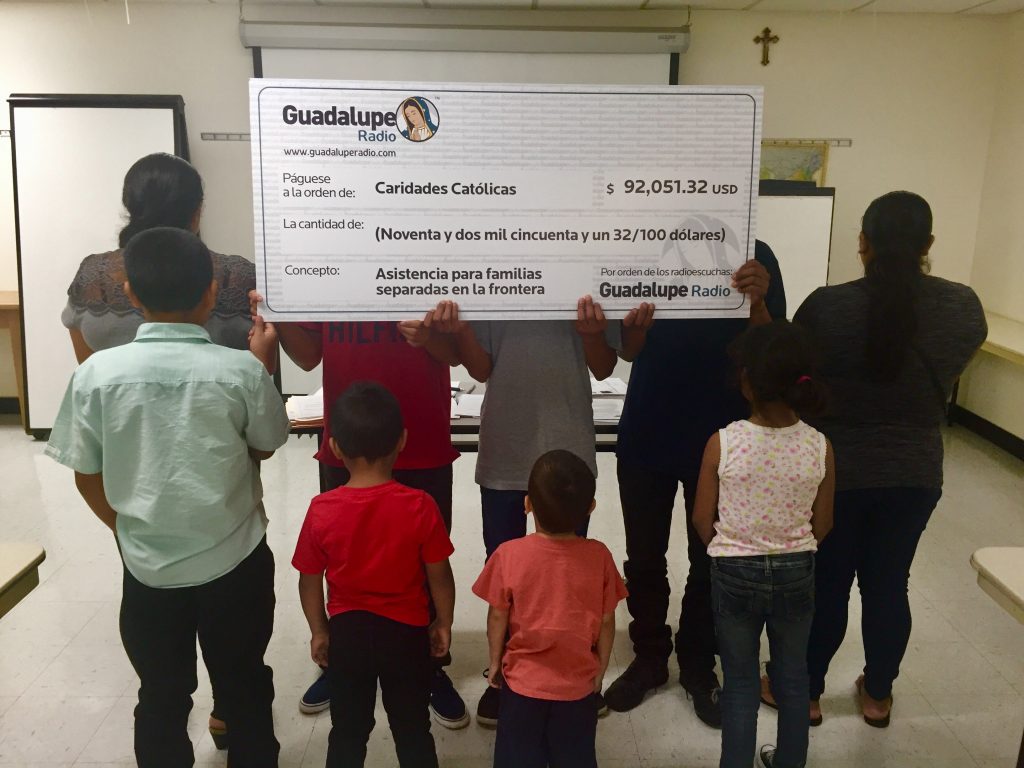

Esperanza doesn't normally have the resources to deal with this number of people at once, but the Catholic community came together to help. Over the last two days of August, Spanish-speaking listeners of the Catholic station Guadalupe Radio donated a total of $94,000, in small increments, to help the families.

“It was amazing; the community surpassed all our expectations,” said Isaac Cuevas, director of Immigration and Public Affairs for the archdiocese, who helped put together the two-day “radiothon” to raise money for the effort.

“Our initial goal was to raise $30,000 to help 20 families. But the need was larger, more people arrived and a miracle occurred. On the first day of the marathon, we realized that we would easily raise more money. We had an average of 24 to 40 calls an hour. People came in person, or sent envelopes with checks,” Cuevas said.

The people donating were from a very similar demographic of those families that had just arrived after their long journey and family separation, he added. “They primarily sent money in small amounts: $20, $40, $100. One donation went up to $1,000, but most were small.”

“Many of the donors have probably been in the same situation and are very sympathetic to the migrants,” said Carrillo of Catholic Charities. “They even had children coming with their piggy banks donating their savings. Money also came from different parishes.”

Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez, who visited the border at the beginning of July as part of a delegation of bishops, said that the separation of families was a “cruel consequence of our broken immigration system and the failure of leaders in Washington.

“I am inspired by this initiative of Catholic Charities and Guadalupe Radio — it is a beautiful sign of compassion and it will make a big difference in the lives of these little ones and their families. But at the same time, we need to keep praying and keep working for the reform of our immigration laws — which is too long overdue,” the archbishop told Angelus News.

In the meantime, thousands of immigrant families who are reunited after weeks or months of separation still have to put together some kind of normal life while they wait for a process that may end up sending them back to the country they fled.

Most came from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, countries where deep poverty conspires with extreme levels of gang violence to provoke a refugee crisis that has gone unacknowledged as such by the U.S. government.

The human cost is deep and troubling, said Ortiz.

“This zero tolerance has been pretty terrible for both parents and children. Many parents ended up in places that were not prepared to take them,” she said.

A Guatemalan mother, who briefly spoke during the Guadalupe Radio radiothon, explained that she was separated from her two children and that the siblings were also sent to different places.

Besides taking care of their basic needs, those working with the families are mindful of their emotional needs as well.

“Aside from representing them and offering other help, our main priority is the client, not to do anything to traumatize them again,” said Ortiz, who added that the money will help hire more legal help for a program that was already at capacity before the crisis worsened this year.

In the meantime, caseworkers, lawyers, and others keep trying to make the families feel welcomed and supported. But most of them, like the young man from Honduras with the little girl, can barely talk about what they went through.

Ortiz summed it up this way: “The majority of the clients shut down and don’t want to talk to anyone.”

But they still have a long and exhausting fight ahead of them.

Pilar Marrero is a journalist and author of the book "Killing the American Dream.” She worked as a political and immigration writer for La Opinion and a consultant for KCET's Immigration 101 series.