As he does every Saturday, Oscar Vasquez arrived one recent September evening to St. Patrick’s Church in North Hollywood with his guitar in tow to sing at Mass. While the rest of the parishioners trickled in and greeted one another, someone offered tamales for sale next to the parking lot. The sound of fast-paced Spanish language conversation filled the air.

Vasquez walked slowly toward the church, limping a bit. He just had knee replacement surgery, the only thing that could possibly keep him from joining the trip that more than 50 others in the church have been planning excitedly.

Otherwise, he could have never imagined not joining them for the journey of a lifetime: the canonization of El Salvador’s Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero by “el Papa Francisco” in Rome.

It’s a big day that’s fast approaching after what has seemed like a long wait.

On Oct. 14, 2018, the martyred archbishop of San Salvador killed in 1980 by a gunman while celebrating Mass will become St. Romero (“San Romero”), more than 37 years after his assassination.

But today, so many years later, Vasquez has a very good reason to feel connected to Romero. As he tells the story, he gets a little bit emotional, can’t finish a few sentences, tears up and pauses.

It all started with a call to a wrong number back in the late 1970s, when Vasquez was dialing some clients, and somehow he got through to the Archdiocese of San Salvador, and a familiar voice picked up the phone.

“I’m Archbishop Romero.”

The words coming from the other side of the line shocked Vasquez for a moment. He didn’t mean to call there, but somehow it happened.

And this changed everything for Vasquez and his family, as he recounted.

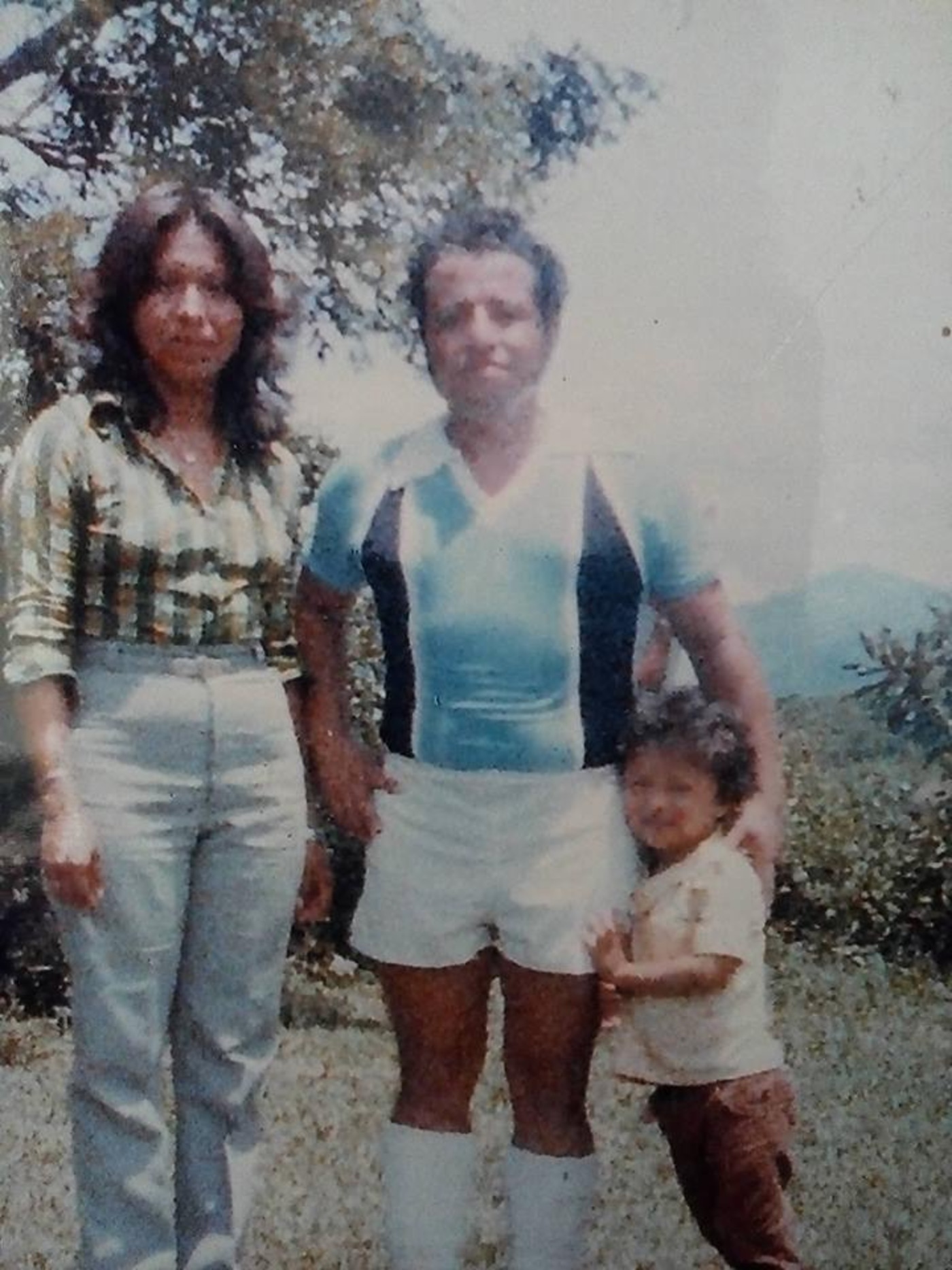

“My 3-year-old son had been ill for a while, in and out of hospitals. The doctors had found a congenital heart condition that needed surgery. We took him home several times, but there was a doctor strike and then an outbreak of infection in the hospital, so the intervention was postponed over and over again,” Vasquez explained.

When Romero picked up the phone, the man told him he always listened to his Sunday homilies on the radio, a custom of the archbishop, who broadcast from the cathedral every week.

“I told him about my son,” Vasquez recalled. “He immediately said, ‘What’s your son’s name? Do not worry, put your son in God’s hands. Have faith. I will pray for him and he will be OK.’ ”

After that conversation, Vasquez took his son out of the hospital for the last time, and soon, as violence got worse in the country where a civil war was brewing, decided to move to the United States with his wife and two sons.

He took with him all the medical paperwork they had accumulated and immediately started visiting specialists in New York, where they would live for two decades before moving to Los Angeles.

“I took him to this doctor, one of the best cardiologists I could find. She said: ‘Who told you that this child is ill? Your son is completely healthy. He has no problem in his heart.’ ”

For Vasquez, this was a miracle delivered through the “wrong” number he dialed, a miracle performed by his faith and by Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

That may be the reason why he’s not completely despondent about missing the canonization. “I went to the beatification in El Salvador and it was beautiful, and I think his becoming a saint is wonderful. He fought for the poor at a time when no one could do it, and he paid with his life,” the elderly man said, “but to me, he was already a saint.”

‘A dream come true’

A couple of days later, several dozen parishioners sit in a sweltering bungalow next to a soccer field in front of the church. The parish priest, Father Nicholas Sanchez, stands in front of the room explaining details of the trip: “Don’t take a big suitcase, it is a mistake,” said the priest, smiling. “Just like in life, we must carry little baggage if we can.”

The group of mostly Salvadoran parishioners is showing nervous excitement. Many raise their hands repeatedly to ask about this or that detail. “Should we wear the same color for the ceremony?” “Are we going to see the pope?” “How much money do we need and do we buy Euros here or there?”

A woman interrupts the discussion of practical details to thank the priest, who a while ago suggested they travel together to Rome as they did to the beatification in May of 2015.

“It’s almost a dream that I never dared to have,” said one woman. “Thank you, father,” said another.

Sanchez knows Rome pretty well and is leading his flock to the “origins of Christianity as it relates to martyrdom” and to participate in the canonization, he explained. Aside from being present in the ceremony, Sanchez is planning to celebrate at least three Masses with his group in different sites of historical significance. He seemed as excited as they are.

A tall, lean man, Ricardo Castillo, is one of the participants who will travel with his wife to Rome. He hopes that the first Salvadoran saint in history will make a difference for his birth country.

“I came here in ’86 during the war,” he recalled. “I never met Romero but I was on my way to the cathedral for his funeral when all hell broke loose, there was a lot of violence that day. I didn’t think we were going to make it.”

Some see the killing of Romero as the real start of a bloody war that lasted for 12 years and killed more than 100,000 people, but Castillo thinks that the situation in El Salvador is even worse now.

“There’s so much violence, one cannot even go out at night,” he said. “Sometimes we ‘salvadore√±os’ talk about this situation right now as worse than the war. At least then we were used to it.”

El Salvador currently competes with Honduras for the title of “most violent country” in the Americas, as the two Central-American nations are deeply shaken by violent gangs and poverty. Things, according to Castillo, haven’t changed that much.

“Maybe ‘San Romero’ will help,” he said, with a sad smile.

Los Angeles celebrates

The City of Angels has the largest Salvadoran community outside of El Salvador, and many of those who revere the martyred archbishop and can’t go to Rome are preparing to mark the occasion with activities here.

Between 12 to 15 people are traveling from St. Thomas the Apostle Church in the Pico-Union area of Los Angeles, according to María Echeverría, a spokeswoman for the parish. The rest, she said, will hold a vigil in the church and watch a live broadcast of the ceremony at 4 a.m., local time.

The Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Dolores Mission in East LA, Blessed Sacrament Church in Hollywood and several other churches will hold celebrations, Masses, and vigils.

Mount Saint Mary’s University showed a digitally restored version of the 1989 film “Romero” and held a panel discussion on the impact of Blessed Romero in today’s world. we

Ana Grande, dean of undergraduate programs at the university who helped organize the film and panel event, will also travel to Rome to celebrate the canonization of Romero, who was a good friend of her uncle, Father Rutilio Grande.

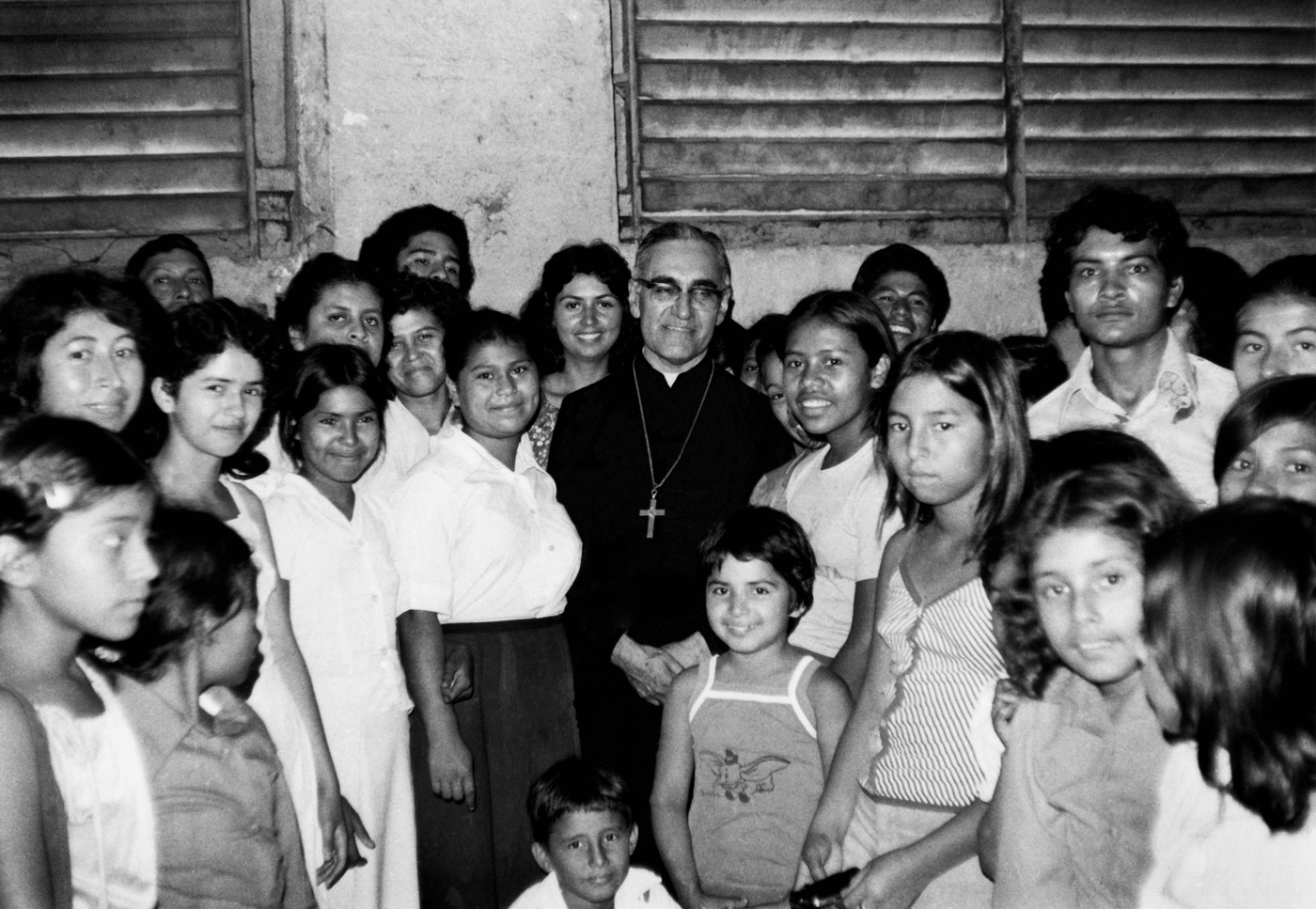

It was Father Grande’s assassination, in 1977, which led to Msgr. Romero’s transformation in reputation as a traditionally conservative bishop into a staunch defender of the poor and the exploited being “disappeared” and massacred, mostly by the security forces of the country.

“At that time, Romero had just been elevated to archbishop and he was seen as a conservative,” Grande said. “Rutilio was just the opposite. He was trying to implement the Second Vatican Council, started ecclesial base communities, and said one had to pray with one’s feet by being with the people.”

Romero and Grande met in the seminary years before and became friends. The killing of Grande marked the beginning of a campaign of persecution of the Church in El Salvador and it shook Romero to the core.

“Romero said, if he gave his life for his people, why shouldn’t I? That’s when he radically changed his approach,” Ana Grande said. “You couldn’t have a Romero without a Rutilio Grande.”

After Grande’s death, during the last two years of Romero’s life he accused the security forces and the Salvadoran government of being the leaders of the repression. The archdiocese didn’t only pray for peace, but it worked for justice by hiring lawyers to document the disappearances and killings.

‘Microphones of God’

Maria Hilda Gonzalez is used to microphones. She is a television host for El Sembrador, a Catholic TV station. She and her family own several relics of Blessed Romero, among them the microphone that was used by the archbishop to deliver his homilies in San Salvador.

She and her husband picked the microphone up from the floor during the confusion that ensued in the cathedral during the archbishop’s funeral in 1980. She had met Romero a few years earlier during church activities and at the funeral of Grande.

“We believed he was a living saint,” Gonzalez said. “These 37 years were like a long night. We know not everyone in our country or community agree with his canonization, but we believe that’s due to ignorance, that people don’t know about him. And for years we have tried to educate people about who he was.”

She will travel with several members of her family to participate in events surrounding the canonization and is taking the microphone with her, one of the relics of Romero that her family owns. The other relics include the manuscript of his last homily, an autographed photo and a piece of cloth with his blood from the day he was killed.

“His message was prophetic and his canonization means we need to live up to his example,” said Gonzalez. “He always said that if one voice is silenced, we are all called to be the microphones of God.”

She is glad that Pope Francis helped push the canonization of the first Salvadoran saint in history, which was delayed for many years.

“Justice prevails,” she said. “We will be there to celebrate that God is just and that we have more reasons than ever to show the world who he is.”

Pilar Marrero is a journalist and author of the book “Killing the American Dream.” She worked as a political and immigration writer for La Opinion and as a consultant for KCET’s “Immigration 101” series.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!