The Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins is now considered one of the great Victorian poets, but in 1866 he decided to give up writing poetry for Lent. In 1868, upon his entrance into the Society of Jesus, he burned all of his poems—convinced he could not live as both a poet and a priest. Although he began writing again a few years later, he was continually wracked by the tension between creation and devotion; between the confidence necessary for art and the humility necessary for faith.

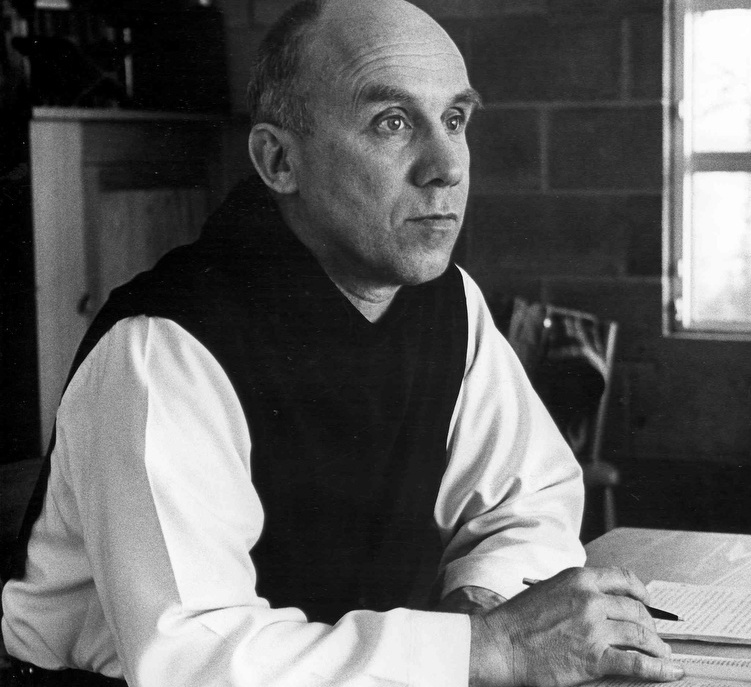

Nearly 80 years later, another poet-priest felt the same struggle. Thomas Merton lamented “this shadow, this double, this writer who had followed me into the cloister.” “He is supposed to be dead,” Merton writes, “but he stands and meets me in the doorway of all my prayers, and follows me into church. He kneels with me behind the pillar, the Judas, and talks to me all the time in my ear.”

Although best known for his prose contemplative work, Merton was nonetheless a prolific poet, having studied under Mark Van Doren at Columbia University. Merton maintained contact with Van Doren even after leaving the school, and his influence never wavered: Merton noted “I ended up being turned on like a pinball machine by Blake, Thomas Aquinas, Augustine, Meister Eckhart, Coomaraswamy, Traherne, Hopkins, Maritain, and the sacraments of the Catholic Church.” More than simply an influence, Van Doren handed Merton’s first manuscript, Thirty Poems, to James Laughlin at New Directions, who later published the collection.

Merton truly believed in the power of poetry. “I think poetry must / I think it must / Stay open all night / In beautiful cellars.” His essay “Poetry, Symbolism and Typology” helps explain his approach to devotion and poetry. He argues that “to say that poems have meaning is not to say that they must necessarily convey practical information or an explicit message.” Rather, the poet “seeks above all to put words together in a such a way that they exercise a mysterious and vital reactivity among themselves, and so release their secret content of associations to produce in the reader an experience that enriches the depths of his spirit in a manner quite unique.”

“The Widow of Naim,” a poem from his 1946 collection, Man in the Divided Sea, is a great example of how Merton represented the Bible in his creative work. The Naim sequence only lasts seven verses (Luke 7:11-17), and is often lost between the Capernaum centurion and Christ’s reflection on John the Baptist. In Luke’s version, Christ arrives at Naim along with his disciples at the same time a man “who had died was being carried out.” Christ tells the mother of the man, the titular widow, to not weep. He touches the bier—a support for the coffin—and the “bearers stood still.” Christ tells the dead man to arise, and he does. Because this section of Luke’s Gospel is enigmatic, it is ripe for a Catholic poet to consider and reimagine.

In Merton’s poetic version, the initial focus is not on the arrival of Christ, but instead on the gravediggers and the mourners of the town, who, “White as the wall . . . follow / to the new tomb a widow’s sorrow.” His focus is on tactile description, particularly color: graves are cut in “grey rocks” by men who move “more slowly than the sun,” their countenances “white.”

The citizens of Naim move down the hill; they are met by “strangers.” Merton does not make it clear whether this group—“Some smell of harvests, some of nets”—is the disciples or the adjoining crowd following Christ. Merton connects those who arrive and depart: as the mourners move more slowly than the sun, those accompanying Jesus ascend the hill “more slowly than the seasons of the year.” This arriving crowd speaks with a much different tone than the perceived mood of the men from Naim: “Why go you down to graves, with eyes like winters / And your cold faces clean as cliffs? / See how we come, our brows are full of sun.”

The sun overbears and slows the mourners. In contrast, the arriving crowd has smiles “fairer than the wheat” and eyes “saner than the sea.” Merton’s poetic structure and style allows Christ to reside behind the lines, his potential actions narrated by his representing crowd. Christ remains silent throughout the entire poem. This crowd does offer some solace to the mourners: “Lay down your burden . . . And learn a wonder from the Christ.” Merton’s approach makes even clearer the symbolic juxtaposition between life—Jesus and his followers—and the death-like mourners. Additionally, the promise of “a wonder” is prefiguring of the miracle to come.

Yet Merton adds even another layer of complexity to his poem. The next nine lines are a parenthetical indent, an oblique address to the reader, admitting that “those old times / are all dried up like water,” and that the “widow’s son, after the marvel of his miracle: / He did not rise for long, and sleeps forever.” The man was resuscitated, not resurrected; his gift of life was an ephemeral one. Luke would most likely agree with Merton here, but Merton appears to have had another motive: the parenthetical address allows him to represent the miracle as a continuum, a call for the modern man he so often hoped to reeducate. Merton plays the role of preacher as realist: “And what of the men of the town? / What have the desert winds done to the dust / Of the poor weepers, and the window’s friends?”

The poem ends with a dramatic address: the men from Naim observe the person and power of Christ, and see the ultimate reason for the miracle—not to give the dead man temporary life, but so that “we may read the Cross and Easter in this rising, / And learn the endless heaven / promised to all the widow-Church’s risen children.” Within the poetry of Thomas Merton we find these subtle, yet moving, gifts. We are lucky that he and Hopkins found poetry and devotion compatible.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.