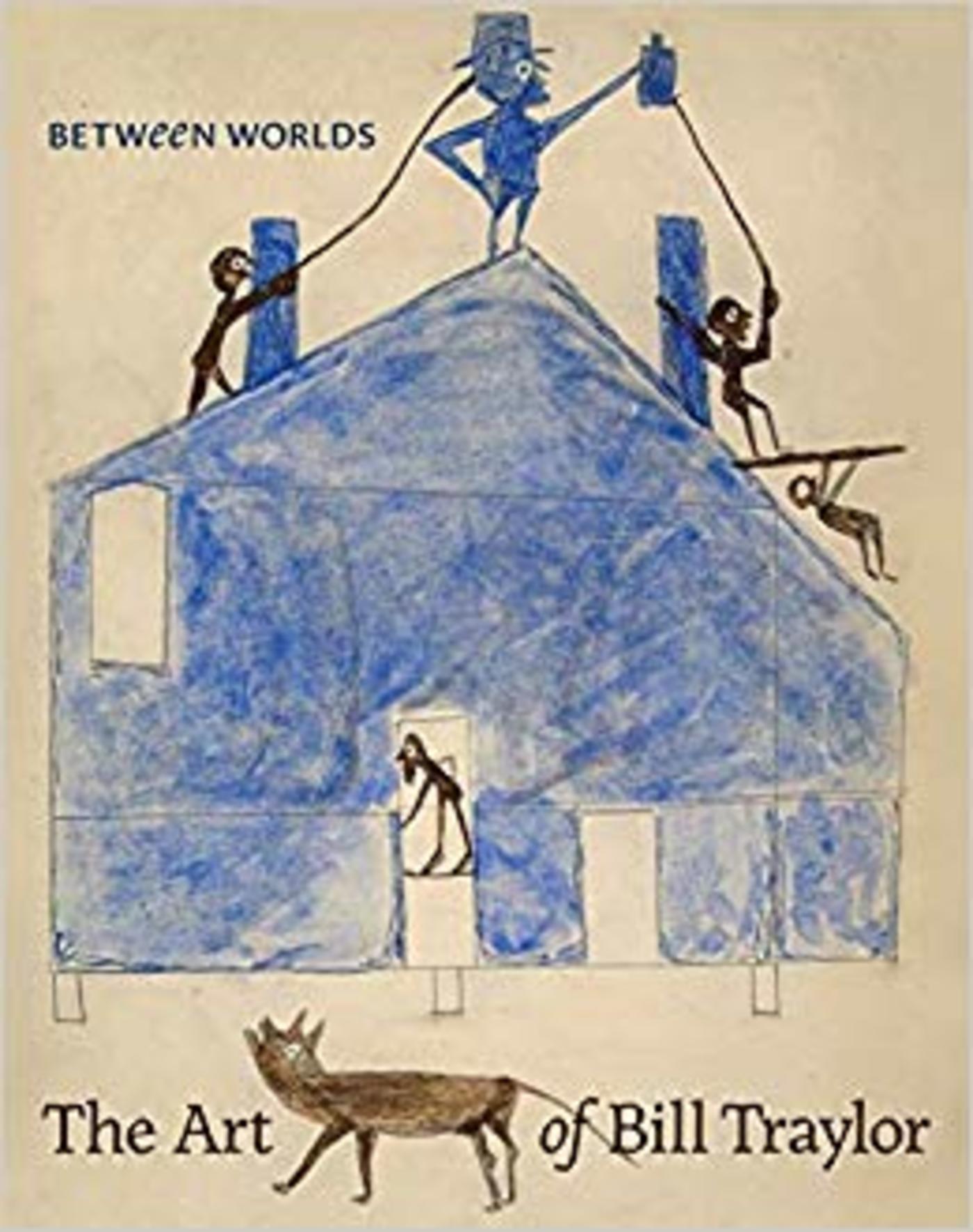

Bill Traylor “was a twentieth-century artist, known for his simple yet powerful distillations of tales and memories and brilliant use of color, but in important ways he remained a nineteenth-century man,” writes Leslie Umberger of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her curated volume of Traylor’s life and work is a narrative and visual accomplishment; a beautifully-presented book that captures the marvel and struggle of Traylor’s life, and the uniqueness of his work.

Born into slavery in 1853, Traylor lived an entire life before his street-corner art reached an audience. Traylor was creating work for several years before capturing the attention and support of the largely white Montgomery, Alabama art community. Some research suggests that he began drawing around 1937, but we might date 1939 to 1942 as his significant work period. He produced roughly 1,200 works, all untitled.

The painter Charles Shannon, a lifelong Montgomery resident, describes a scene from 1939. Traylor “was sitting on a box on the Monroe Street sidewalk. He had a white beard and was bent over. It looked like he might be drawing. When I got close to him I could see he had a little straight-edge stick and was ruling lines with the stub of a pencil on a small piece of cardboard.”

Traylor had been living in Montgomery for over a decade by that point. Widowed, his children grown up and gone away, he repaired shoes for some years, before settling to his daily work spot, “in front of a timber-plank fence that enclosed a blacksmith’s shop.” The scene was captured in an early drawing of Traylor’s that depicts the array of tools and actions. At the top of the panel is a surprise: a whiskey-drinking man about to be clubbed on the head.

Umberger describes Traylor’s themes as “[hovering] ambiguously between horror and humor . . . The way Traylor depicted violence is highly animated (figures’ arms flailing, hands energized, and eyes wide); it is easy to read the scene as raucous and funny and dismiss the underlying but ever-present brutality.

Traylor’s artwork was locally known, but a cadre of artists known as the New South (Charles Shannon, Blanche Balzer, Paul Sanderson, and others) curated his work into a February 1940 exhibition. Traylor continued to grow and evolve as an artist; as Umberger notes, “He was not plodding along learning realism or figure drawing but rather, ambitiously working out an abundance of ideas at once, both representational and abstract.”

His voluminous output included many different subjects, but perhaps his most arresting work includes what Umberger describes as “haints, hags, tricksters, and beasts.” He sketched tall, lithe characters “with suits and hats” whose identity might be “the preacher, the conjurer, the Devil himself.” Traylor’s ideas of the devil were largely shaped by what folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett has described as the African American vision of the devil as “a very real individual, generally anthropomorphic, but capable of taking almost any form at will.” In that vision, when the devil takes human form, he is often gentlemanly, formal, and devious. The devil is also connected to music, specifically the blues—not only were talented musicians thought to have sold their soul to the devil, but legends suggested that their music was the connection between this world and a more spiritual realm.

It is difficult to accurately define what influenced Traylor, since he was more interested in creating art than explaining his artistic vision, but one thing is clear: he was concerned with “heaven and hell” in his art, and in his life.

In 1944, at 91 years old, Traylor was baptized into the Catholic faith at St. Jude Church in Montgomery. Historian Mechal Sobel has noted that Traylor’s grandson was a student at St. Jude’s school for several years, and a member of its first graduating class in 1942. Sobel conjectures that St. Jude’s focus on a black congregation, coupled with health services and social outreach, would have appealed to Traylor. More complex elements are also likely. Sobel writes that by “converting, Traylor chose to do exactly what the white Protestants in control in the South would not have him do.” Additionally, Traylor “would have known that Catholicism was a home for the veneration of saints.”

Although Traylor wasn’t known to speak often of religion and faith, his unique drawings—and their implication of how Christ’s crucifixion and southern lynching existed on a continuum of punishment and suffering—establish him as an important Catholic visual artist. His work is suffused with mystery and singular vision, and is worthy renewed attention and appreciation.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, Esquire, The Atlantic, and is a Contributing Editor for The Millions. He is writing a book on Catholic culture and literature in America for Fortress Press.