Two published works released last month, one by a pope and the other by a blogger, describe and analyze ominous signs forewarning a large-scale breakdown of peace, order, justice, and the common good.

These signs include fractious polarization, ideological colonization, widening social enclaves, and economies that discard society’s most vulnerable.

The first of those texts, Pope Francis’ new encyclical “Fratelli Tutti” (on fraternity and social friendship) addresses those realities directly, calling for radical solidarity with the poor and marginalized and a reorientation of economies and lifestyles that contribute to the “throwaway culture.”

The other is “Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents” (Penguin Random House, $27) by conservative cultural critic Rod Dreher (formerly Catholic, now Eastern Orthodox), which draws parallels between contemporary America and Eastern Europe under Marxist communism. It offers readers disheartened by the cultural shift toward secular progressivism a “manual” on how to survive the difficult times to come.

While Pope Francis and Dreher are two names that you won’t often find mentioned in the same sentence, both are offering a bird’s-eye view of the state of our world and what the Christian mission looks like at a critical moment in history. And they both articulate a similar warning to readers at this point in history: We cannot carry on as we have been. We need a drastic change of course.

These warnings came just in time for the 2020 U.S. general election, seen by many as a chance to change course, at least at the political level.

On Nov. 3, Americans elected Democratic former Vice President Joe Biden to the presidency. The 77-year-old Catholic defeated President Donald Trump, whose record while in office on issues such as abortion and religious liberty elicited support among many Catholics, but whose crass brand of rhetoric, hardline stance on immigration, and nationalist approach to foreign policy has drawn direct criticism from others, including the pope, who just recently called his family-separation policy at the U.S.-Mexico border “cruelty of the highest form.”

The aftermath of this election is expected to bring at least two of the things Pope Francis and Dreher warned about to the fore: on one hand, heightened political polarization and distrust of “the other” on a scale the modern world has not seen in decades; on the other, the advance of secular progressivism, championed by the media, cultural influencers, universities, and corporations.

To be clear, Pope Francis’ encyclical is part of the Church’s ordinary magisterium; Catholics are obligated to strive to assent to its teaching. Dreher’s thesis does not carry with it that weight.

And while the two texts look at our current crises through different lenses and speak to different audiences, they share some similar insights and worries, chief among them how fear, isolation, and individualism are shaping our geopolitical landscape as well as dividing families, neighborhoods, and the Church.

For American Catholics, the post-election situation that awaits is a call to once again answer a timeless question: How can we live a life of holiness amid all this — mess?

Two diagnoses

Dreher’s book is written through the lens of historical memory, that of Christians who resisted Soviet totalitarianism. He takes his title from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s counsel in “The Gulag Archipelago” to “never knowingly support lies” — to preserve one’s integrity, even if it comes at a great price.

Dreher believes that U.S. soil is fertile for what he calls a “soft totalitarianism” to take root. He borrows his definition from German-born American political philosopher Hannah Arendt, who says that under totalitarian rule, “an ideology seeks to displace all prior traditions and institutions, with the goal of bringing all aspects of society under control. Truth is whatever the rulers decide it is.”

Fidelity to a new ideology will not initially come from the government, Dreher argues. Instead, cultural elites and corporations will drive conformity.

Dreher writes that all of this will be undertaken in the name of “social justice.” While he lauds an impulse toward care for the downtrodden, he says that it is divorced from the Christian tradition from which it was born. Today’s concept of social justice “depends on group identity and … achieving justice means taking power away from the exploiters and handing it to the exploited.” Anyone who stands in the way is to be removed.

“Christians cannot endorse any form of social justice that denies biblical teaching,” Dreher writes, including sexuality, family, and the dignity of every human person, which are the building blocks of a just order.

Dreher’s concern, and that of his anticommunist interviewees, is that embracing these goods in practice and in public is now characterized as hateful. Christians are losing jobs, livelihoods, and reputations for their commitment to their faith claims. Non-Christians, too, are worried; “cancel culture” is quickly spreading, and unlike Soviet Russia, it takes no prisoners.

Like Dreher, Pope Francis invokes the lens of historical memory as a way of looking at the “dark clouds” gathering over the world. He uses the example of St. Francis of Assisi, his namesake, to look at our present condition.

“In the world of that time, bristling with watchtowers and defensive walls, cities were a theater of brutal wars between powerful families, even as poverty was spreading through the countryside,” he writes.

Pope Francis shares a number of Dreher’s concerns about economies of exclusion. He, too, worries about how digital platforms are changing communication, producing enclaves in which like-minded groups perpetuate groupthink and in which opponents are demoralized or eliminated.

“Persons or situations we find unpleasant or disagreeable are simply deleted in today’s virtual networks; a virtual circle is then created, isolating us from the real world in which we are living,” he laments.

The Holy Father likewise condemns the neoliberal deification of consumption and individual rights, and juxtaposes it with the universal destination of goods and radical hospitality. He warns against populist movements that appeal to people’s worst inclinations and fears, and calls politicians to remember their vocation to serve the common good.

The antidote is a global commitment to treat every person as a brother or sister, loved by the same Father. According to Catholic writer Brandon McGinley, “The Holy Father envisions a free, open, tolerant, welcome, fraternal exchange of ideas and culture as the path to social peace based on truth.”

He believes deeply what St. Paul says, that every person has the natural law written on their hearts. As Christians, we are to appeal to those inclinations by being good neighbors.

Heroic discernment

Given this grim outlook, how is the Christian to proceed? Dreher encourages readers to engage in a threefold process of discernment made popular among Christian dissidents under Soviet rule by the Jesuit priest and anticommunist activist Father Tomislov Kalokavic: “See. Judge. Act.”

“See meant to be awake to realities around you. Judge was a command to discern soberly the realities in light of what you know to be true, especially from the teachings of the Christian faith. After you reach a conclusion, then you are to act to resist evil.”

The heroes in “Live Not By Lies” include Czesław Miłosz, the Polish poet and literary critic, who was exiled for his dissidence; Karol Wojtyla (later St. Pope John Paul II), who helped to preserve Poland’s cultural heritage and memory through underground gatherings, and ordinary men and women who lost material security for refusing to acquiesce.

Though Dreher acknowledges that this has not yet come to pass, the fact that any shared understanding of and respect for liberal principles like equality, fraternity, and justice between Christians and those in power does not bode well. Christians must turn their effort to resisting the forthcoming aggression.

This includes building up strong families and transmitting the faith to children. It involves preserving historical memory, which is essential for culture. And it means modeling moral courage at home and in public, no matter the cost.

“Our cause appears lost … but we are still here,” Dreher concludes. “Now our mission is to build the underground resistance to the occupation to keep alive the memory of who we were and who we are, and to stoke the fires of desire for the truth God.”

All in the same boat

Incidentally, the “See. Judge. Act” approach is one that the Holy Father is known to use: It is central to his vision of how to engage with the modern world and to some of his most important writings, from “The Aparecida Document,” whose drafting he oversaw at a meeting of Latin American bishops in 2007, to his 2015 encyclical on the environment “Laudato Si” (“Praise Be to You”).

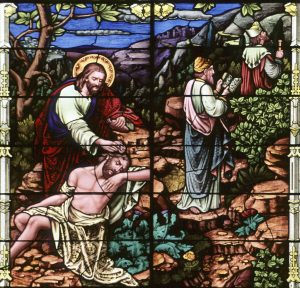

Pope Francis uses the parable of the good Samaritan as our lens for discernment. In his view, the Church is still the field hospital, and we are to consider every person (particularly the marginalized) as the man left half dead on the side of the road, ignored by the people with the power to help him.

These moments don’t call for resistance, or the perpetuation of an “us” versus “them” mentality. Instead they demand that we reach out our hands, even to those who consider themselves our enemies.

The Good Samaritan rose to the occasion not because he was not concerned with the question, Who is my neighbor? but rather, What kind of neighbor are you?

It is clear to Pope Francis that a good number of people are in a great deal of pain. The polarization, isolation, and anger we see are symptoms of much deeper wounds, namely spiritual ones. They need the Savior, and Christians are called to make that introduction.

“A worldwide tragedy like the COVID-19 pandemic momentarily revived the sense that we are a global community, all in the same boat, where one person’s problems are the problems of all,” he writes in “Fratelli Tutti.” Once more we realized that no one is saved alone; we can only be saved together.”

So which historical moment is more instructive? Which is the way forward? Are Christians in the United States called to resist cultural pressure by retreating into churches and homes, preserving and passing on the Faith in its fullness? Or should we reach out our hand to our neighbors and appeal to their natural instincts for good?

Perhaps it’s best to take a “both/and” approach. As the dust settles from this fraught election and campaign season, we will be faced with opportunities at home, at work, in our parish, and on our social media platforms to discern how to speak, pray, and act.

The Church has produced saints in all historical circumstances: St. Francis and St. Pope John Paul II lived in two different moments, and both responded to the promptings of the Holy Spirit.

In a homily on All Saints’ Day a few years ago, Pope Francis said that like stained-glass windows, the saints allow the light of God to permeate the darkness of sin in the world. The Christian’s task in the days ahead is to determine how to best let the light shine through.