He played his entire Major League Baseball career in one city, and that city remembers Roberto Clemente as the ancient Greeks remembered the heroes of their epics.

Pittsburgh has named a major bridge in Clemente’s honor and raised a monumental bronze statue of him. There is a museum dedicated to the minute examination of Clemente’s life — in the game and beyond. This year an artist unveiled a colossal mural overlooking the interstate highway.

In Pittsburgh he’s still called “The Great One,” 40 years after his death. Jerseys with his number, 21, remain the standard equipment for fans of the Pirates.

What was it that made Clemente larger than life — and makes him larger in death?

At root, it was arguably the quiet intensity of his Catholic faith.

He did everything with intensity, and almost everything seemed to revolve around baseball. But baseball was not something removed from his faith. “I am convinced,” he once said, “that God wanted me to be a baseball player. I was born to play baseball.”

And the statistics bear out his claim. He was a four-time National League batting champ, once the league’s Most Valuable Player. He batted a lifetime .317 with 3,000 hits. He was the first Latin American inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Roberto Clemente was born in 1934 in Carolina, Puerto Rico, the seventh child in his working-class family. His father, Melchor, was a nonpracticing Catholic. His mother, Luisa, had abandoned the practice of the Catholic faith and then belonged to a Baptist church. The parents had Roberto baptized a Catholic, but on Sundays he went with his mother to Baptist services.

Luisa, like most people who knew him, remembered him as a serious child — and unusually religious. Following a pious custom, he would ask his parents’ blessing, their “benedición,” when leaving the house. He enjoyed going to church and singing hymns. According to his mother, his favorite went like this:

Sólo Dios hace al hombre feliz.

Sólo Dios hace al hombre feliz.

La vida es nada.

Todo se acaba.

Sólo Dios hace al hombre feliz.

Only God makes a man happy.

Only God makes a man happy.

Life is nothing.

Everything passes.

Only God makes a man happy.

Young Roberto was diligent about attending the funerals of his neighbors and urged other family members to join him. In adolescence, as he gained an athlete’s strength, he was often recruited to be a pallbearer at the rites.

Puerto Rico in the 1940s was divided and stratified by class rather than race. The Clemente family was black, but that did not mean any disadvantage to them or to their son. While still a teen, he rose from sandlot to professional ball on an island that prized baseball and whose leagues played the game all year round. His skill conferred a kind of stardom.

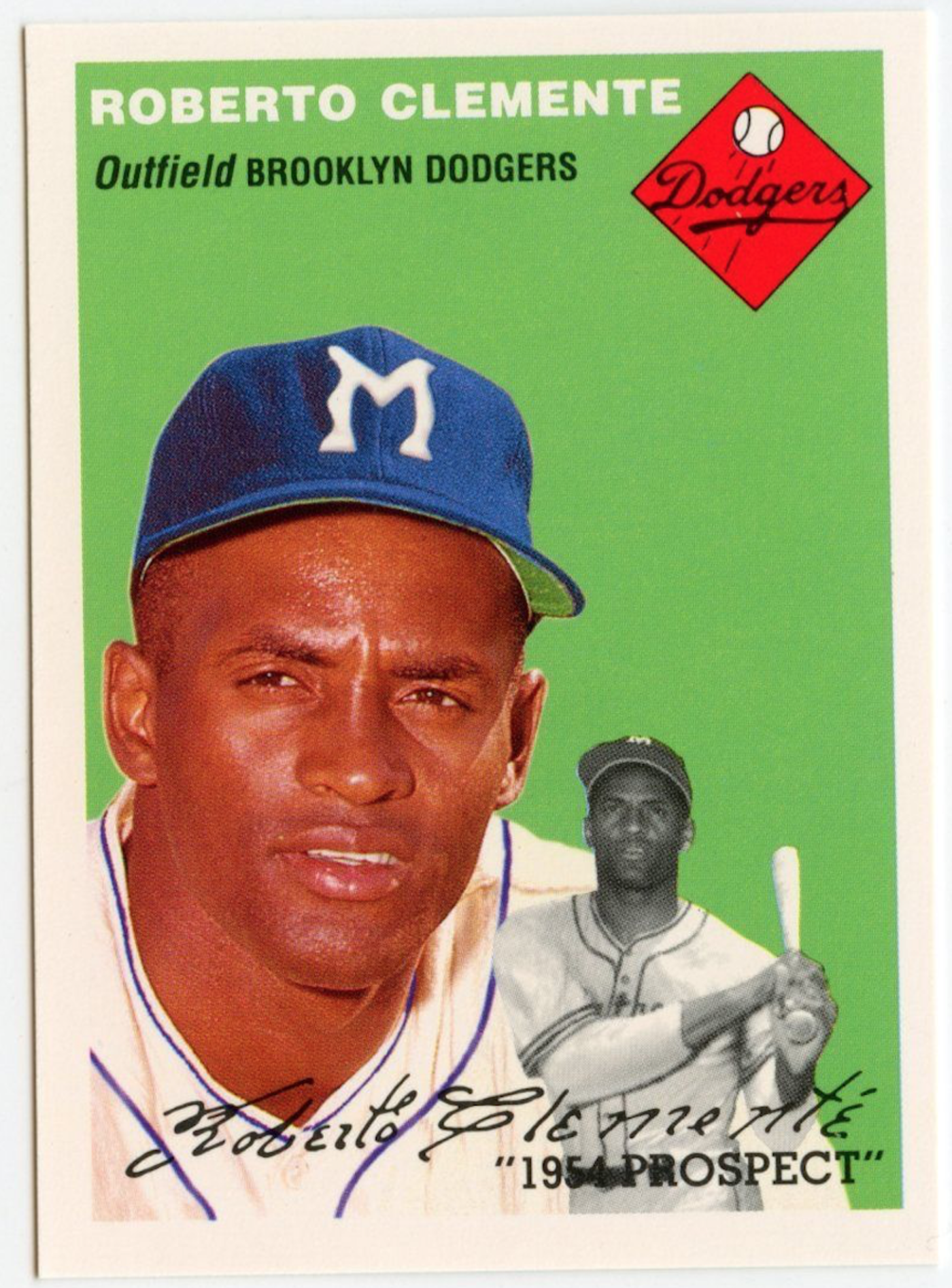

In 1953 he attracted the notice of several U.S. major league teams, and a bidding war broke out for his contract. He chose the Brooklyn Dodgers, who offered him a $10,000 signing bonus.

Roberto Clemento’s minor league baseball card when he played ball for the Brooklyn Dodgers in Montreal, Québec, before signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates. (ROBERTOCLEMENTE.SI.EDU)

It was the Dodgers who had, just six years earlier, broken the major leagues’ color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson. But a black player was still a curiosity — and often a target of scorn from fans, opposing players, and even teammates.

A black Latino, like Clemente, faced a double disadvantage. Though a fiercely intelligent man, he struggled with English, both in comprehension and in speaking. He was often misunderstood — and he often misunderstood the words and intentions of others.

The Dodgers assigned Clemente to their Triple-A minor league team in Montreal. Playing in Canada and the States, Clemente encountered race hatred for the first time. After a game in Montreal a fan warned him that he should never again speak to a white woman.

The Dodgers tried to hide Clemente in Montreal, playing him only intermittently and actually pulling him from games when he was hot at the plate. But his skill was undeniable. And when the Dodgers failed to bring him up to the parent team, the last-place Pittsburgh Pirates made a play for him. The next year he was in Pittsburgh’s starting lineup.

Clemente’s new home was a multiethnic city, but Latinos made up just a tiny portion of the population. He often felt isolated because of his difficulties with English. With the sportswriters he developed a reputation for hypersensitivity. His teammates and coaches considered him a hypochondriac.

But he had been living with severe pain, in his back and his shoulder, since an automobile accident in 1954, the year before his promotion. And the racial and cultural clashes were just as real.

Pittsburgh, moreover, was far from the nation’s media capitals. So Clemente’s spectacular play went largely unnoticed until the Pirates’ defeat of the New York Yankees in the 1960 World Series.

That same year, an activist priest in Pittsburgh found reason to complain on Clemente’s behalf. In his weekly column in the diocesan newspaper, Father Charles O. Rice observed:

“Other stars, no greater than he, have been paid handsomely all year for endorsements and appearances, but not Clemente. This proud fellow found out that as a Negro he just naturally gets a great deal less money. … In the sum of the world’s pain and injustice, a small thing, but indicative of the horrible normalness and ghastly ubiquity of racial prejudice in the United States of America.”

Gradually, though, he settled into Pittsburgh, and the natives loved him for his play. Some ballplayers had a reputation for carousing, but Clemente didn’t drink or womanize.

He found Puerto Rican connections in the city, among them Henry and Elsa Coolong, both devout Catholics. Years later they would recall that their friend’s choicest pleasures were Chinese food, horror films on TV and excursions to nearby drive-in theaters.

Every year he spent the off-season back home in Puerto Rico. When he was very young he played winter ball there, but the Pirates eventually asked him to restrict his activity to scouting, in order to avoid injuries.

In December of 1963, while on the island, he met Vera Zabala and instantly fell in love with her. They carried on a long-distance courtship in the year that followed. Clemente even paid for her to fly, heavily chaperoned by family members, to see him play in New York. They were married the following winter.

At some point in early adulthood, Clemente had turned again to the Catholic faith of his baptism. Some who knew him credit a priest he knew as a teenager. With his marriage to Vera, however, he began to integrate the Faith into his life.

In 1964 he met a Spanish priest newly arrived in Pittsburgh after studies in Puerto Rico. His name was Father Alvin Guttierez. Years later Guttierez recalled, “I was a stranger here and he welcomed me.”

Roberto and Vera developed a deep friendship with Guttierez and another Pittsburgh priest, Father William Cheetham. “They came over on Sunday nights,” Cheetham would later recall. “Their kids were small. It was a very close family. They were very friendly.”

Though Clemente could be testy with the press — and distant with fans — he developed a local reputation for helping children and poor people. He made frequent hospital visits. He was also extremely generous to panhandlers. His friends would sometimes protest as he handed over a 10 or a 20, but Clemente would respond, “The Lord put me on this earth to help people.”

He was intensely private about religious matters. Some of his teammates were Evangelical and Pentecostal Christians, and they tried “witnessing” to him, to persuade him to abandon the Catholic faith. But they said he seemed completely uninterested in the conversation.

Thanks to his mother’s example, he kept a broad and deeply ecumenical approach to life and friendship. He continued to cherish the hymns he had learned as a Baptist. When he endorsed a Pittsburgh music business, they rewarded him with an electronic organ for his home. He played by ear and enjoyed picking out the melodies of his favorite hymns from childhood.

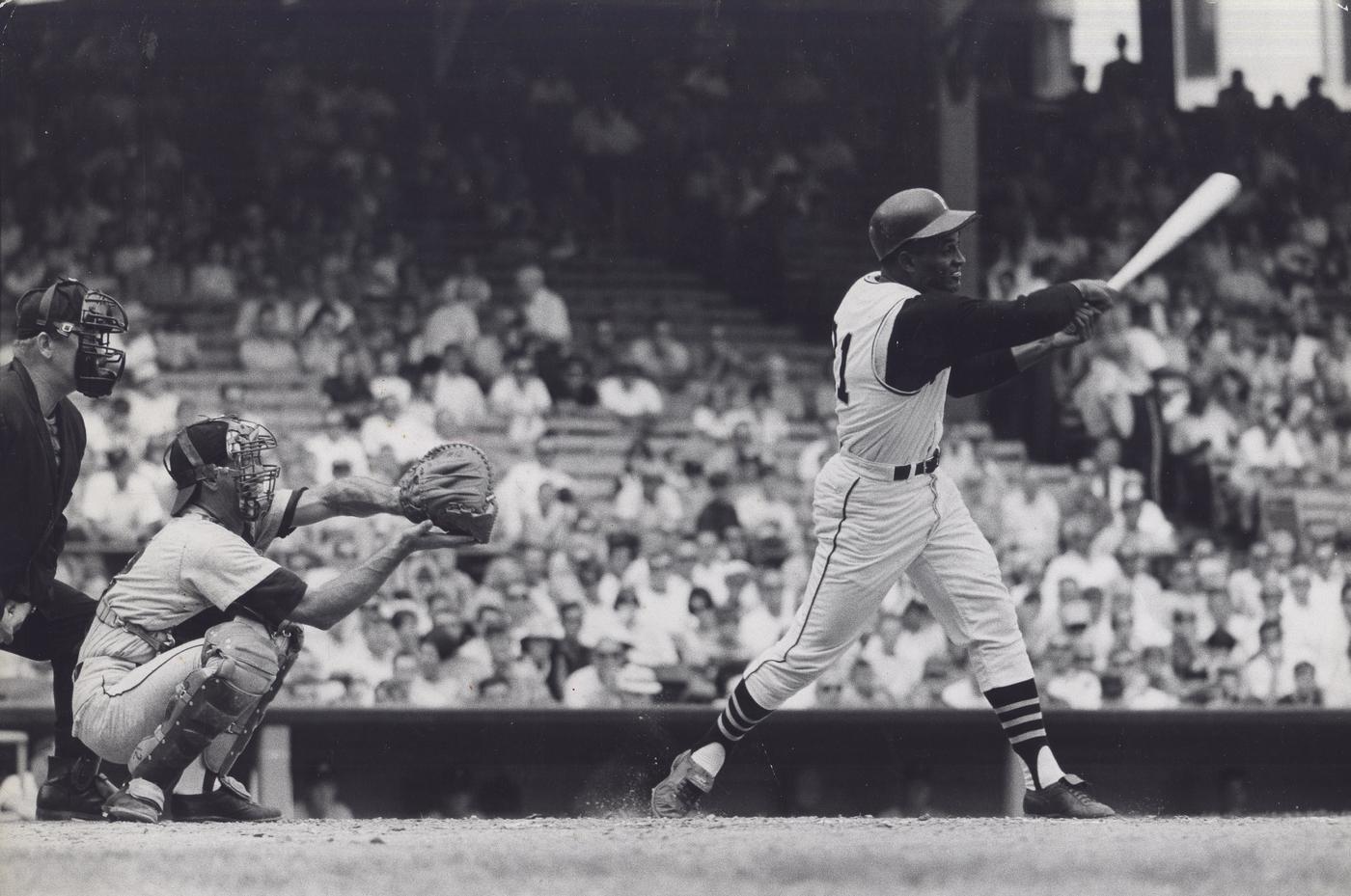

On the field, he sustained his spectacular performance through the 1960s and into the 1970s. Despite his chronic complaints of pain, he never saw his numbers dip appreciably. In fact, many sportswriters consider the 1971 World Series his high point. And he continued to make baseball history.

On Sept. 1, 1971, in a game against Philadelphia, Pittsburgh fielded the major leagues’ first-ever all-black starting lineup, with Clemente in right field.

As he approached the major milestones of his career, sportswriters would ask him for predictions: When would he gain his 3,000th hit? But he would routinely consign the future to God. In his later years, he tended to spend more of his off-season doing charity work.

He gained his 3,000th hit in his final at bat of the regular season in 1972. The Pirates had entered the season as world champions, but lost the National League title to the Cincinnati Reds in the playoffs.

That fall the Clementes returned, as usual, to Puerto Rico. On December 23 they heard the news that Managua, Nicaragua, had been devastated by a major earthquake. The government in Puerto Rico asked Clemente if he would serve on a committee to provide relief.

He agreed and threw himself into the task, personally collecting food, clothing, toys, and other items. He himself booked the plane and loaded it.

He made plans to accompany that first shipment to Nicaragua on New Year’s Eve. In the days leading up, his family and friends later recalled, he worked almost around the clock.

The plane took off as scheduled, but never arrived at its destination. It crashed into the ocean immediately after takeoff, killing the crew, Clemente, and a friend who had accompanied him. His body was never recovered.

In Puerto Rico and in the United States, there was an immediate outpouring of grief. The president of the United States, Richard Nixon, was one of many people who took up Clemente’s cause and donated to Nicaraguan earthquake relief. National organizations — the Holy Name Society, the Teamsters — pledged large sums as well.

The Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, waived its waiting period and inducted him immediately. (Today, Clemente is one of only three players honored with a statue at the museum’s entrance. The other two are Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson.)

At a memorial Mass in Pittsburgh, more than 1,500 mourners jammed into a church built for 800. According to press reports, the grief-stricken fans were “standing three deep behind the last pew on the first floor and balcony.”

Father Guttierez eulogized his friend as a “unique human being who had deep compassion for his fellow man.” Preaching in both Spanish and English, he said, “Wherever there was need, there was Roberto Clemente,” a man “of great convictions who was practicing the art of helping others when he died.”

What were those convictions? They were, Guttierez reflected years later, Clemente’s “Catholic ethos.”

Clemente never presented himself as a model disciple, and while he was alive no one proposed him as one. He was touchy and easily offended. He had an explosive temper that he vented on sportswriters, fans, and even friends. Like many denizens of the locker room, he was known to drop F-bombs and take the Lord’s name in vain.

Yet since his death fans have repeatedly proposed his name for sainthood. In August 2017 many news outlets — including the Washington Post and Christian Newswire — reported that Pope Francis had already beatified the ballplayer, declaring him “Blessed.” But that turned out to be fake news, quickly denied by the Vatican.

His most recent biographer, David Maraniss, called him “Baseball’s Last Hero,” and that may be the most fitting honor. Baseball writer Wilfrid Sheed put the matter well:

“Clemente could sometimes seem like a pest, a nagging narcissist, with only his burningly serious play to deny it. Yet when that plane crashed carrying relief supplies to Nicaragua we saw what he had meant all along. It was like the old Clemente crashing into the right field wall in a losing game: the act of a totally serious man.”

What motivated his seriousness? By his own admission and from the testimony of his friends, the answer seems clear.

Some years ago, Clemente’s friend Father Cheetham told journalist John Franko: “We know [Clemente] was a great sports figure, but more than that he was a great humanitarian. He was a good, religious man. That’s what we should remember.”

Clemente’s widow, Vera, agreed: “My husband was a very religious man. His faith guided him to help others.”