The Marymount Institute for Faith, Culture and the Arts was founded in 1991. Theresia de Vroom, a member of the original board, has been director since 2006.

“Adding on to what my predecessors started, I began to change what we were doing. Our mission became an interdisciplinary and open dialogue about faith, culture and the arts, all the while representing the mission of the Marymount tradition and the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary. Over time, we were able to bring in a Nobel laureate, an artist-in-residence, and a publisher.”

The Institute offers lectures, film screenings, internships, a chapel-center for peace and prayer and a sculpture garden. All the events are free and open to the public.

“There’s a place for academic discourse and we do that sometimes. But mostly I want everything that comes through here to be accessible to anyone: Catholic, non-Catholic, student, faculty and the community at large, including your granny.”

For example, the Institute has featured several events with the noted writer-activist Wole Soyinka in conversation with other leading scholars and thinkers. They’ve had actors Patricia Clarkson and Alfre Woodard, and playwright Beth Henley. They’ve screened films like “Teza,” by the Ethiopian filmmaker Haile Gerima.

Elias Wondimu, who had already founded Tsehai Publishing, came to Soyinka’s first talk.

“That’s how we met,” Theresia says. “I’d thought of starting a press but I didn’t know how. Elias joined us in the fall of 2007 and we established the Marymount Press. In conjunction with Tsehai, we published our first book a year later.”

In 2008, the Institute did an African marketplace based on Soyinka’s poem “SAMARKAND: Markets I Have Known.” They wanted to highlight the art that comes out of the marketplace and staged the event in the sunken garden in front of LMU’s Sacred Heart Chapel.

“The diversity in our city and university community was represented at the market place. We had mariachis; we had Aztec dancers. We also did the original medieval consecration of the church in which they have to expel the secular as if it were the devil. It was the middle of the night. We had the Easter fire blazing. Our then-President Father Lawton did the hyssop blessing with the aspergillum outside the church. Then four Orisha priests broke the kola nut, which is the communion of the Yoruba, and poured the palm wine, which Father Lawton accepted as a gift from them. Talk about an interreligious moment.”

That eucharistic thrust is part of the reason Theresia, an ace cook, personally prepares the food for the book launches, many of the events, and in this case, our afternoon interview.

The Marymount Institute is an activist press. Their commitment is to tell human stories and to produce books that are excellent across the board.

“So far we have published plays, academic books and spiritual books. We have a meditation on ‘Piers Plowman,’ a 14th-century poem that’s about a poor man who meets and learns the lessons of Jesus,” says Theresia.

Elias adds, “If you select any of our books and compare it to a similar book by, say, Oxford University Press, I’ll guarantee that ours is not very far away. The quality of the stock, the photographs, the cover, the layout.”

Perhaps the least visible and most important work of the institute, however, is the mentoring. Students are invited to participate and collaborate in every step of the publishing process. In so doing, they learn what it takes to create a book, from the editing to the art.

“We tell the interns in the interview, ‘We’ll trust you. We’ll give you an assignment. And whatever you return will determine what you get next.’ You can see their faces change. Right away they want to step up to the plate.”

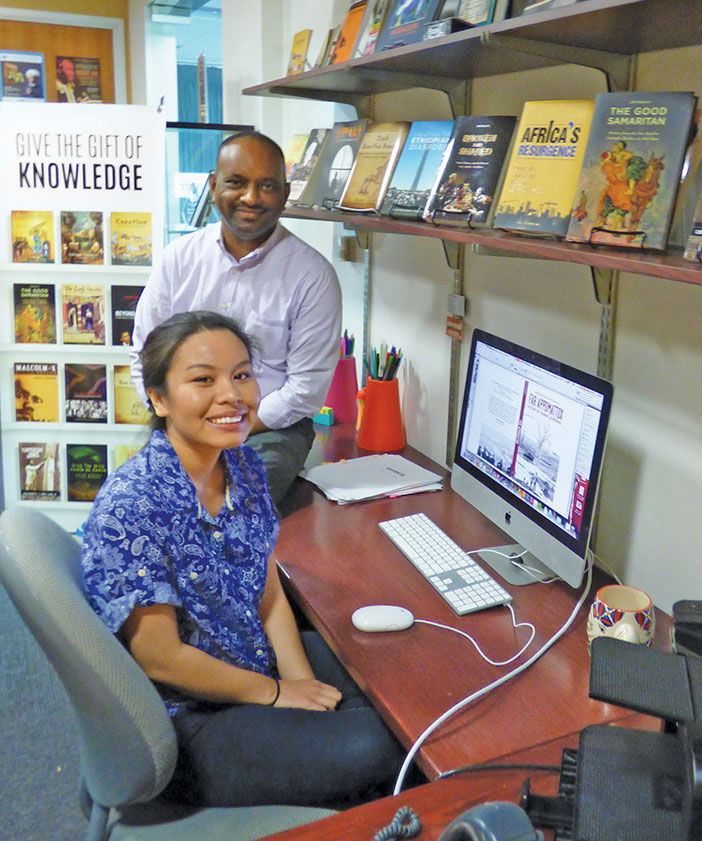

Recent graduate Sara Martinez designs the posters and book covers. “She’s a genius,” says Elias. “She went from being a shy student intern to a full-time staff member now supervising interns, and designing all these books.

“I remember she was working as a summer intern. She comes on time; she goes on time. Every afternoon around 3 her phone rings and she panics. I say, ‘Why?’ ‘It’s my father,’ Sara replies. ‘He’s come to pick me up.’”

They didn’t know till then that Sara lived in Irvine.

“My father drove me in every morning from Orange County,” Sara admits. “He dropped me at work, went to a movie or a bookstore, then returned at 3 to bring me home. I owe a lot to my parents.”

Elias adds, “This is our dream. To mix it up, to change the world by presenting something that’s not yet available in this form, to empower students and push them out to the world.”

Then he gestures to the feast prepared by Theresia — seared salmon, frisée salad, fresh raspberries and cream — over which we’ve been chatting.

“Besides, where else do you get to be a student where someone cooks you a beautiful meal?”