One way to tell things in the Vatican aren’t going especially well is when papal spokesmen are obligated to deny that the pope is “embittered,” which is what happened August 29 following bombshell accusations from a former papal ambassador in America that Pope Francis knew about misconduct allegations against ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick five years ago and covered it up.

Italian news agencies moved a story on August 28 that close aides to the pope have described him as “embittered,” leading to the round of official denials the next morning. Instead, those denials asserted, Pope Francis is actually “serene” and “resolved.”

Whatever the pope is actually feeling, it’s hard to imagine he isn’t reeling at least a little bit from one of the most turbulent summers any modern pope has ever experienced, probably since Blessed Pope Paul VI issued “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”) in July 1968.

To wind back the clock, at the end of July the pope accepted the resignation of McCarrick from the College of Cardinals, in the wake of allegations that McCarrick had engaged in sexual misconduct with seminarians and, in at least one case, sexually abused a minor.

Then on August 14, a Pennsylvania grand jury released its long-awaited report, documenting cases involving 300 predator priests and 1,000 child victims in six dioceses over a 70-year span.

Those two developments, combined with the ongoing clerical abuse scandal in Chile, ripped open old wounds for the crisis and set the tone for the pope’s August 25-26 trip to Ireland for a Vatican-sponsored World Meeting of Families.

In the end, Pope Francis met with abuse survivors and addressed the scandals four times in six public addresses, vowing “firm and decisive measures” in the pursuit of “truth and justice.”

Yet on the second day of the pope’s trip, he found himself under fire on yet another front: An 11-page statement from Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò alleging that when Archbishop Viganò was the pope’s envoy in the United States in 2013, he personally informed Pope Francis that the former Washington prelate had “corrupted generations of seminarians” and had been subject to discipline for that reason under Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

Pope Francis responded to those claims — sort of — in an airborne press conference en route to Rome from Dublin Sunday night, saying he “won’t say a word” about them and basically challenging journalists to look for themselves.

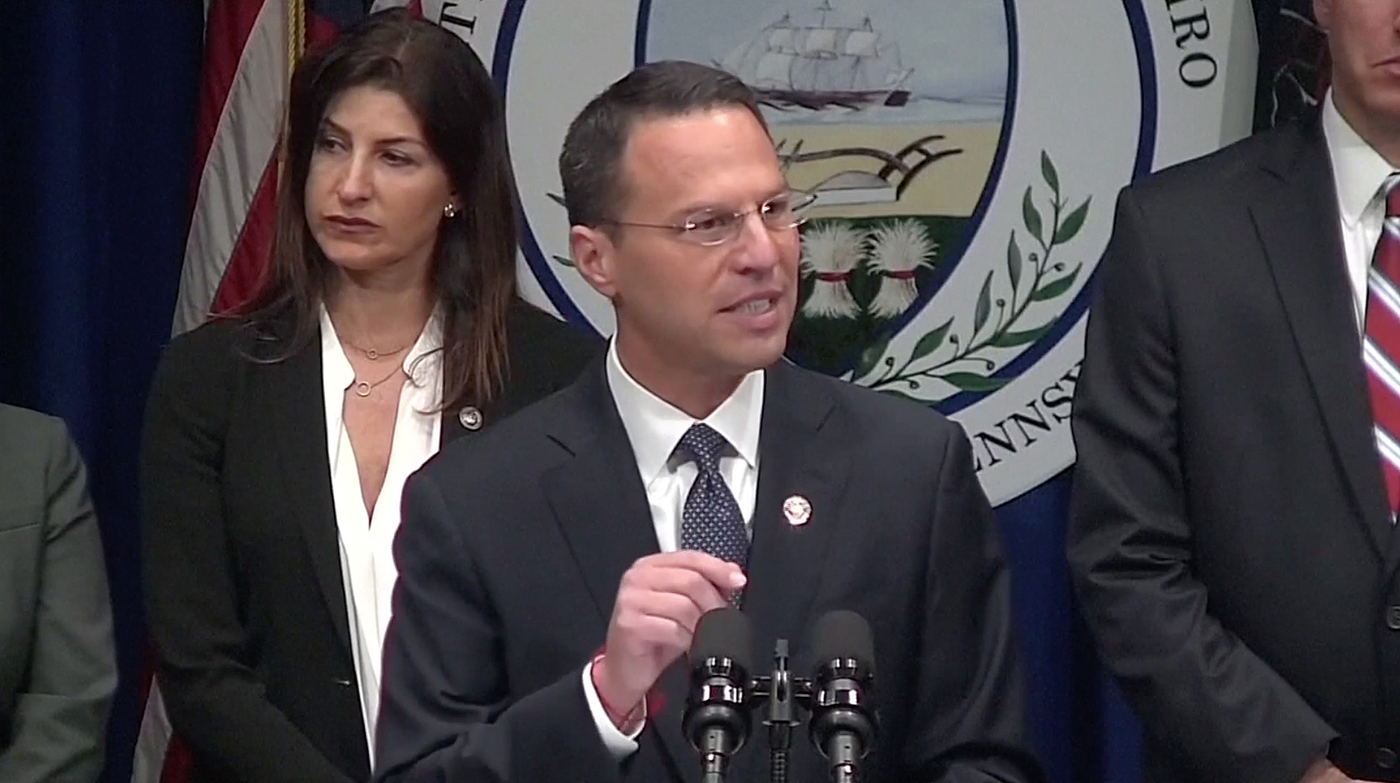

As the shock waves from Archbishop Viganò claims continued to be felt, Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro held a press conference August 28 in which he asserted that the cover-up of cases documented in the grand jury report reached “all the way up to the Vatican,” though adding he couldn’t address Pope Francis’ personal responsibility.

Nor is there much breathing room in the immediate forecast for the pope. Cardinal Daniel DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, issued a statement in the wake of the archbishop’s charges saying that officers of the conference will soon be making their way to Rome to meet Pope Francis, seeking his support for their plan to investigate breakdowns in the McCarrick case.

To be sure, there’s no public sign of a bunker mentality in the Vatican quite yet. In Ireland, the pope drew warm and enthusiastic crowds — admittedly much smaller than St. Pope John Paul II’s historic 1979 journey when more than half the country turned out, but still pumped-up and visibly moved by being in the pontiff’s presence.

For a beleaguered Irish Church, the visit amounted to a badly needed shot in the arm.

Back in Rome on August 29, the pope seemed relaxed and in good spirits at his weekly audience, even quipping at one point about a pilgrimage group from the Italian region of Lombardy that “these Lombards sure make a lot of noise!”

Moreover, to some extent the Vatican’s apparent strategy of allowing Archbishop Viganò’s claims to collapse under their own weight seemed to be working, especially because the former nuncio’s central charge was wrapped in his 11-page letter with accusations directed at 31 other senior Churchmen, with many of them appearing politically motivated and based on little more than innuendo or supposition.

(To make things even slightly more surreal, a journalist who helped break the story on the Archbishop Viganò letter tweeted on August 28 that the former nuncio is now in hiding and “fears for his life.”)

Victims’ groups in various parts of the world tended to express frustration over the fracas, styling it as an internal left-right battle within the Church that has precious little to do with them, and may distract from the pressing work of reform.

On the other hand, a handful of American bishops issued statements in the wake of Archbishop Viganò’s letter attesting to his credibility and calling for an investigation of the charge (Bishop David Konderla of Tulsa, Bishop Thomas Olmsted of Phoenix, Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, Bishop Charles Chaput of Philadelphia and Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin).

Those who spoke in defense of Pope Francis include Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, Cardinal Donald Wuerl of Washington and Bishop Robert McElroy of San Diego.

Media organizations around the world also spent the days after the letter was released looking for evidence that might verify or debunk the letter, suggesting that the questions it raises probably won’t disappear on their own.

What soon became clear is that if the alleged sanctions were ever made, they weren’t very effective. McCarrick clearly kept up a public profile from 2009 to 2013, preaching at well-attended Masses, participating in ordinations and fundraisers, accepting awards (including at least one event where he was praised by a smiling Archbishop Viganò) and even traveling to Rome with fellow U.S. bishops to meet with Pope Benedict XVI.

While it’s impossible to predict where this tumultuous story may go, three things seem immediately clear.

First, at some point the Vatican is likely going to have to give an accounting of what the pope knew on McCarrick, and when he knew it. Even if there is never any conclusive confirmation of Archbishop Viganò’s charges, leaving things as they stand would mean that a chunk of the Church will be forever convinced that the pope was in on the cover-up, making it difficult for Pope Francis to exercise moral leadership.

Second, however the Archbishop Viganò mess shakes out, the immediate reaction to it in the United States provided an x-ray of a badly divided Church, in which how credible one found the charge appeared to be heavily conditioned by one’s political alignment.

Fostering some sort of rough common ground in that context will remain a pressing pastoral challenge, no matter what happens on other fronts.

Third, even if the consensus at the end is that Pope Francis is guiltless on McCarrick, broader questions about his response to the abuse scandals likely won’t disappear either.

Many people in Ireland were upset that he came and went without offering an answer as to how he plans to hold bishops and other Church officials accountable, not simply for the crime of sexual abuse but also the cover-up of that crime.

Even if Pope Francis isn’t “embittered,” therefore, it’s probably safe to say this hasn’t exactly been the smoothest summer he’s ever had — and it’s not clear right now that his autumn is going to prove any easier.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $25! For less than 50 cents a week, get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!