At a small storefront in McAllen, Texas, the worsening humanitarian crisis at the Mexican border is bringing together an unlikely army of volunteers from all over the world.

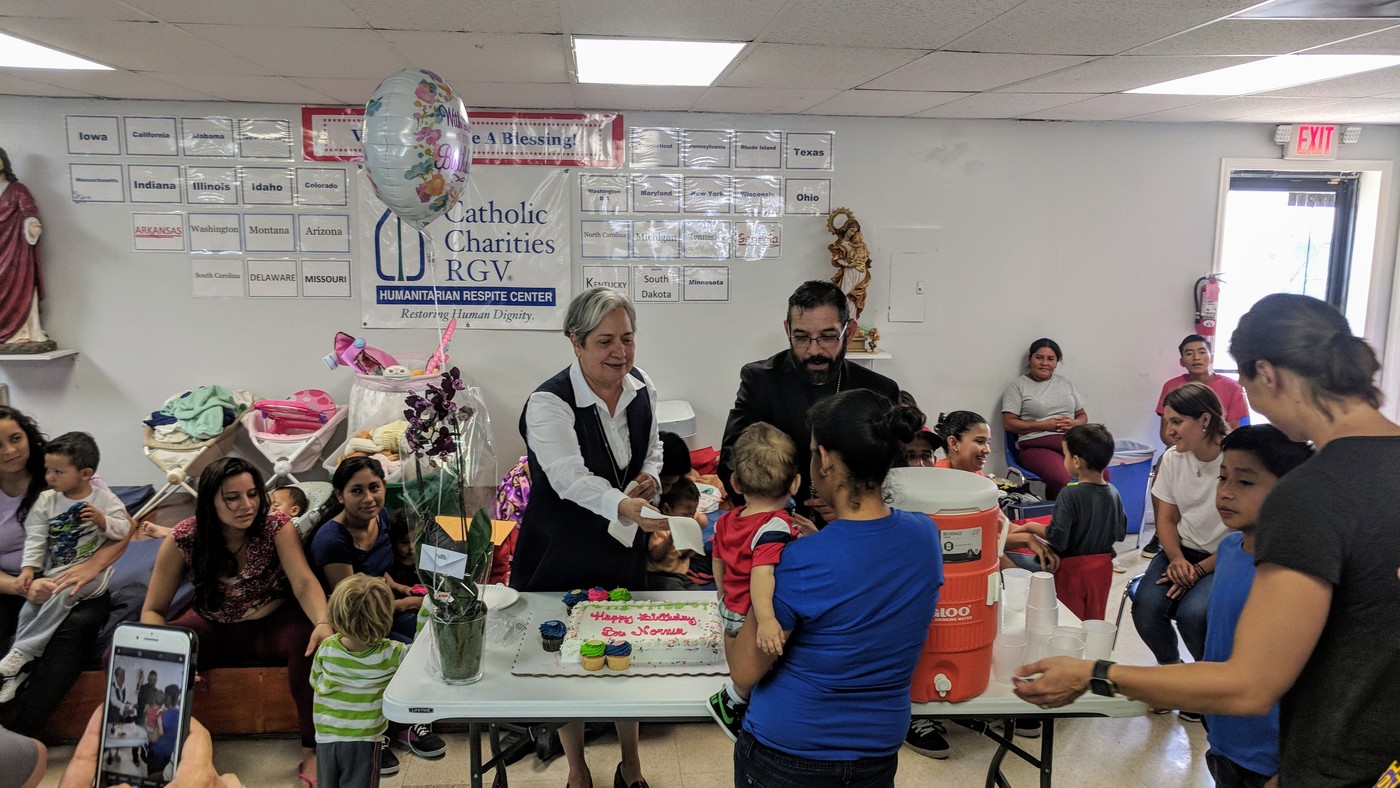

On any given day, you can find Protestants, Jews, and Muslims at the Catholic Charities Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, following directions from Sister Norma Pimentel M.J., executive director of the Diocese of Brownsville’s charitable arm.

The volunteers’ ranks include college students, church groups, political campaign alumni and local families stopping to give donations and a few hours of their time. Some have come from as far away as Indonesia and Spain.

And during a fact-finding mission to McAllen last week, they included several Catholic bishops and a cardinal.

What those prelates were given during their two-day visit wasn’t just a taste of South Texas hospitality, or the chance for a convenient photo-op. They saw the Church literally out in the streets - often in triple-digit weather - building bridges in a part of the country known more for its walls, whether metaphorical or physical.

“For us, this is an ongoing reality,” said Brenda Riojas, Diocesan Relations Director for the Diocese of Brownsville. “There are so many different realities to the immigration story, and we have been living them daily long before 2014 when we saw that initial influx.”

The influx came when thousands of Central American immigrants escaping worsening violence and poverty - most of them from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala - began to reach the McAllen-Brownsville area in droves. Since then, most cross the Rio Grande only to be quickly caught by Border Patrol.

After being apprehended, they are sent to the Ursula Processing Center in McAllen, a warehouse-style complex in a marshy area a few miles from the Mexican border. At night, migrants lay on the ground in thermal blankets, made of thin plastic sheeting that looks like foil. During the day, many pass the time trying to sleep some more.

After being interviewed by immigration officials, some are deported back to their native countries. Others, including unaccompanied minors and children separated from their parents under a Trump administration directive that lasted only weeks, are sent to shelters such as the Southwest Key Casa Padre shelter in Brownsville while they await their fate.

But some are given an immigration court date in the U.S. and a GPS ankle bracelet to ensure they show up. In McAllen, that means being released to the Catholic Charities Respite Center, where they are greeted with a standing ovation from volunteers the moment they step inside the air-conditioned storefront. With help from family members or Catholic Charities, families are given bus tickets to their destination in the U.S.

For most, this is their first impression of the United States outside of federal detention.

“We’re welcoming them to our country. A lot of times they come in and they’ve been through a very difficult ordeal, looking shell-shocked,” explained Lisa Robinson, a schoolteacher and member of Houston’s Willow Meadows Baptist Church on her eighth trip to McAllen as a volunteer.

Although Robinson doesn’t know much Spanish, she can serve the families cold drinks and hang out with the small children who would rather play with a new toy pony rather than, say, take a hot shower.

“Everything you do, they are always very gracious and appreciative for what we’re doing,” she said of refugees she meets at the center. “At the end of their time here they’re relaxed, they’re smiling, they’ve connected with a lot of us in a very personal way, because we’re helping them meet their immediate needs.”

Those immediate needs often require more than a change of clothes, a hot shower or a good night’s sleep.

Many of the migrants come with medical issues caused by the journey or from neglect in their place of origin. When a new batch of families arrives at the Respite Center, the first question they’re asked is, “Who needs a doctor?”

Local volunteer doctors and visiting ones take turns working shifts at the shelter, and migrants - often children - in need of serious medical attention are taken to a local hospital by volunteers.

Then there’s the language barrier, a challenge even in this border town: Some of the migrants from Central America come from villages so remote that they speak only an indigenous dialect. To communicate with them, Pimentel’s staff has had to call family members in the U.S. or ask for help from officials from their native country’s U.S. consulate. When all else fails, Pimentel admits, they turn to Google Translate.

‘A calm in the storm’

“Father, can I borrow your parish for a few days?” Pimentel asked the pastor of Sacred Heart Catholic Church in McAllen over the phone one day in 2014.

The immigrants arriving from Central American countries such as El Salvador and Honduras were dropped off at city’s bus station and left to their own devices after being released from Ursula, and Pimentel was looking for space to shelter the newly-released families before continuing their journey.

A few days turned into three years of the church lending its parish hall to accommodate the migrants. When McAllen city officials noticed the large numbers of migrants arriving to the city’s bus station everyday-and Catholic Charities’ efforts to help them, they sprung into action, helping fill Sacred Heart’s parking lot with portable showers and mobile medical units.

“From that point on, we’ve had 100 percent support from them,” she said of city officials.

The improvised approach has continued at the Respite Center’s current location blocks away. Opened in September 2017, the center sees dozens of volunteers come and go each day carrying donated clothes, toys, food, and baby supplies for the up to 250 migrants that come through its doors daily.

When the floor of the storefront building can’t hold any more people, some go to sleep in local parishes. Others go home with Pimentel to spend the night in her convent.

Pimentel’s role in the crisis had made her arguably the U.S. Catholic Church’s most visible female leader, as evidenced by the University of Notre Dame’s choice to award her the prestigious Laetare Medal earlier this year.

But one of the most important - and fascinating - aspects of the Catholic Church’s operation in the Rio Grande Valley is its relationship with federal authorities.

Ask Pimentel about the politics of the border crisis, and she is adamant: “The border is not out of control,” she insists. “It is not a place that we must ‘secure’.”

“The fact that these families are coming to this country doesn’t make it unsafe,” she said in a recent interview during the bishops’ visit, adding that her native South Texas is one of the safest areas in the country. “I think that as a country we can keep ourselves safe and offer a humane way of treating these families.”

Still, her job requires her to be in touch daily with government officials. At Pimentel’s request, Immigration and Customs Enforcement sends a text message each morning listing the groups of migrants being dropped off at the McAllen bus station throughout the day.

She and Brownsville Bishop Daniel Flores recently sat down with Department of Homeland Security officials and Texas GOP senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn to update them on their situation at the border. She is regularly in touch with ICE director Ronald Vitiello (a Trump appointee) and occasionally meets for breakfast with regional Customs and Border Protector chief Manuel Padilla.

“As soon as he took over, he called me and said he wanted to meet with me,” Pimentel said of Padilla.

She also maintains a friendship with former Department of Homeland Security chief Jeh Johnson, whose wife has visited the Respite Center to volunteer.

A licensed professional counselor, Pimentel admits that the economic side of running the operation is not her strong suit, which is where people such as Howard Buffett come in. The son of the famed billionaire investor first met Pimentel for a late-night dinner in an empty McAllen restaurant two years ago.

“Howard, I need a van,” she told him over the phone a few months later.

Soon after, a van full of blue sleeping mats showed up at the Respite Center.

“I email him and he responds instantly!” says Pimentel with a laugh.

Now, the nun described as “a calm in the storm” by collaborators is moving to give the Respite Center a more suitable home. The property chosen to house it sits next to Sacred Heart, and to build the new shelter, she’s turned to another heavy-hitter: Georgetown University President John DeGioia.

“He wanted to ask me for advice,” Pimentel said of their recent meeting in Washington D.C. Afterwards, Pimentel said she had something to ask him.

“The answer is yes,” DeGioia replied.

“I haven’t asked you yet.”

“Well, whatever you ask me, the answer’s going to be yes,” she recalls him saying.

Pimentel asked for help raising money for the new shelter, to which DeGioia responded by helping launch a national fundraising campaign-albeit one that still relies in part on GoFundMe donations.

DiGioia has also helped organize a competition for the architectural designing of the new center, the finalists of which are expected to be announced in the coming weeks.

But despite the bureaucratic, political and financial complications that come with the seemingly impossible task faced by Catholic leaders in the Rio Grande Valley, those who have seen the Respite Center grow since 2014 stress that the human dimension of helping the migrants is what matters most.

“There’s always a human face and the human face always points us to Christ, in whatever suffering there is,” said Bishop Flores during a homily at the start of the bishops’ visit on July 1.

“Just to give them a welcome and treat a person with respect, that’s all this is,” Flores said. “It changes everything.”