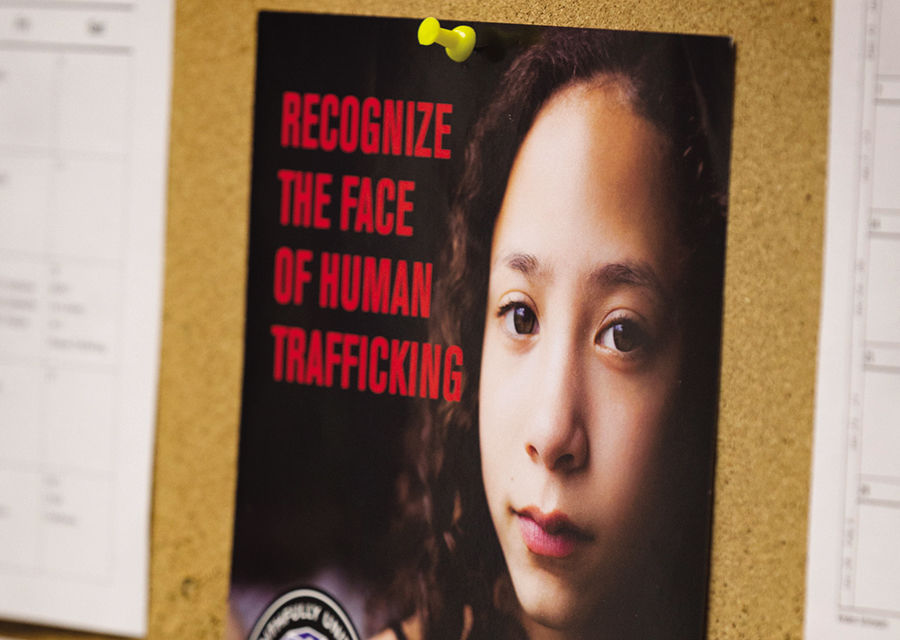

Human trafficking takes many forms. Here are some signs for recognizing them

A young girl picked up daily from school by a much older “boyfriend” and returned home at night to parents none the wiser. A dishwasher at an upscale restaurant forced to work without pay. A performer signing a contract for porn and then being forced into acts she did not agree to.

These are all examples of human trafficking. Unlike most TV tropes, trafficking rarely resembles the sensationalized story of a foreigner kidnapped, shipped and sold. Certainly, these cases do happen. But the majority of trafficking is more normalized, though nonetheless dehumanizing.

As the U.S. State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons explains: “The term ‘human trafficking’ may suggest movement, however no movement is required. It is a crime that can be committed against an individual who has never left his or her hometown.”

At its most basic level, human trafficking is defined as the illegal exploitation of a person, and most often looks like someone forced to work or engage in commercial sex acts without pay and unable to walk away.

“If the trafficker is using force, fraud or coercion to keep them in the situation, it could be considered human trafficking,” L.A. Regional Human Trafficking Taskforce Coordinator Becca Channell told me.

She added that victims are usually held through “coercive means such as threats and severe psychological abuse” rather than physical chains, and “some victims do get paid, although often very little, and this does not discount them from being a victim.”

Contrary to popular belief, human smuggling and human trafficking are not the same things. In human smuggling, a person willingly requests to be moved illegally across borders, although abuses may occur along the way. Human trafficking, on the other hand, is forced, and a crime against the person being trafficked. They do not have to come from another country, state or even city.

Although the National Human Trafficking Hotline receives most of its calls from sex trafficking victims, estimates suggest the vast majority of victims worldwide experience labor trafficking and remain unidentified. According to the California legal code, forms of enslavement can include forced prostitution, domestic servitude, debt bondage or unpaid sweatshop labor.

Victims of human trafficking also span all socioeconomic backgrounds, races, ages and genders. Susan Patterson, a human trafficking educator and founder of Through God’s Grace Ministry, told me that although many people imagine trafficking victims as foreigners, “Seventy percent of human trafficking victims are U.S. citizens with over 60 percent of victims coming from the foster care system.”

Unlike the kidnapped victims in movies like “Taken,” Patterson pointed out that in almost every identified instance of sex trafficking, victims are “teens that are the victims of sexual predators who have gone willingly to meet with them,” thinking this is “another kid or an online boyfriend who has been romancing them.”

When we fall for these stereotypes, it makes it that much harder to identify the most common victims and makes trafficking even more invisible.

Although estimates are hard to come by, the International Labor Organization puts the figure of people trafficked worldwide at 21 million.

The modern-day slave trade is a $32 billion industry and the second largest criminal enterprise worldwide.

Feb. 8 marked the feast of St. Josephine Bakhita, patroness of trafficking victims and the International Day of Prayer and Awareness Against Trafficking around the world. As parishes pray and remember St. Josephine this week, they should also raise awareness of the reality of human trafficking in their own backyard.

rn

What you can do

Parishes that would like to join in prayer and raise awareness of human trafficking should visit archla.org/humantrafficking to learn more.

If you suspect human trafficking, call the CAST LA Human Trafficking Hotline at 888-KEY-2FRE.

Molly Sheahan is projects and programs strategist for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Office of Life, Justice and Peace.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.