During World War II, the eugenics movement hit a wall, says O. Carter Snead. Due to the horrors of Hitler’s ethnic cleansing and genocide, the movement was forced to rebrand “mercy killings of the unfit” with words like “autonomy,” “compassion” and “self-determination.”

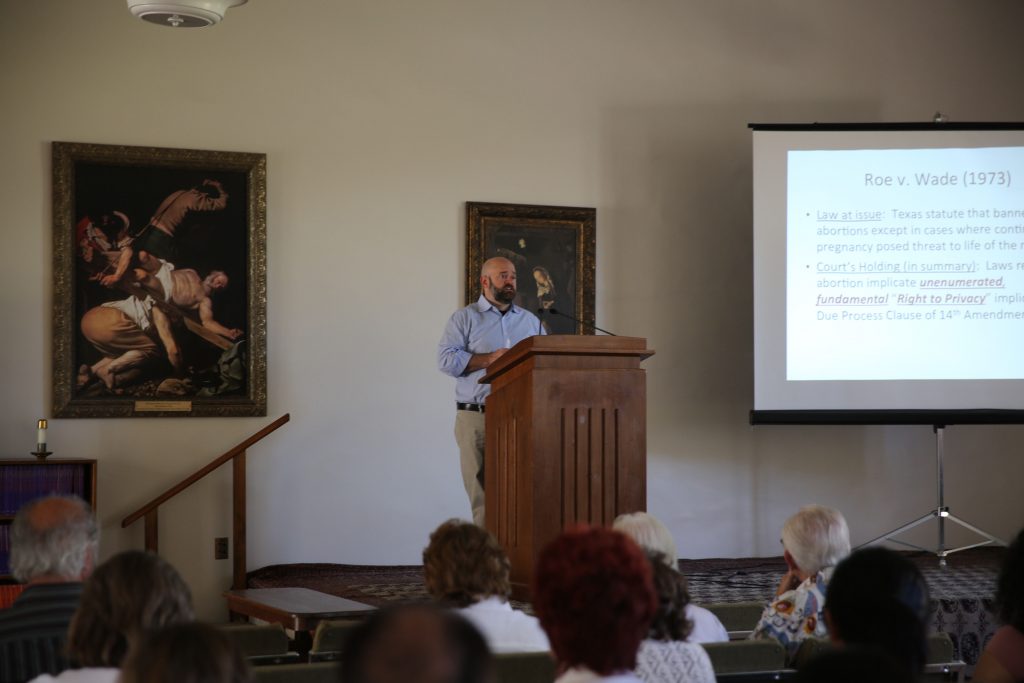

On July 23, as one of the world’s leading experts on public bioethics and a professor of law at the University of Notre Dame, Snead spoke to a crowd gathered at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo during two days of in-depth lectures and discussion on abortion, stem cell research and euthanasia.

During one lecture, Snead used logical secular arguments to counter the arguments used in favor of physician-assisted suicide. “There are liberal progressive people, especially doctors, who oppose assisted suicide and they oppose it … because of these negative side effects, these unavoidable social pathologies that arise from legalizing assisted suicide.”

Snead noted that these negative side effects “fall disproportionately on the shoulders of the poor, the elderly, the stigmatized, the minority.”

The argument from autonomy — the argument that “It’s my life. How is it your business?” — doesn’t work, says Snead. Though many argue that assisted suicide only affects the person who is asking to die, the reality is that every person lives in a family and community that are deeply impacted from the death of a loved one.

Doctors and medical staff are also involved, meaning that some will be forced to assist in a suicide that goes against their moral conscience. “In the case of Canada where they legalized euthanasia, they are going to force doctors to perform euthanasia.”

Additionally, studies show that people who request assisted suicide “are rarely operating with the full height of their faculty and free from any intrinsic or extrinsic burdens,” he says. “Treatable depression is often the cause for someone wanting to kill themselves.”

He adds, “Suicidal wishes often emerge from intrinsic or extrinsic pressures — financial and emotional — regarding the burden that they impose on others, even though it is a mere perception on their part.”

Although many use the argument of compassion, the feeling of hopelessness and loss of control that leads people to want to end their lives can often be treated with proper depression and pain treatment.

However, a doctor’s efforts to help a terminally ill patient with these concerns have been greatly diminished in places where assisted suicide is legal. In these states and counties, “you see diminished efforts to explore and maintain effective pain management in palliative care and long-term care,” Snead says.

The reason comes down to the cost of treatment. Assisted suicide is cheaper and takes less time than palliative care and pain management. Solutions to medical problems take time, expertise and training. Oregon, which was the first state to legalize assisted suicide, has “terrible marks for pain management” which only got worse when assisted suicide became legal.

Coercion is also a known factor in assisted suicide, with many family members and even spouses of the terminally ill exerting pressure. Insurance companies have also been less interested in funding treatment when the cheapest option is a lethal dose.

Snead’s hour-long lecture referenced many other examples and studies but perhaps the most important is the lesson that other countries can teach. “In the Netherlands we immediately saw assisted suicide give way to euthanasia, give way to non-voluntary euthanasia [ending the patient’s life without their consent], give way to involuntary euthanasia [ending the patient’s life even when they express a desire to live],” Snead said.

The slippery slope continues in the Netherlands with a legal proposal to include granting someone 70 years or older the right to assisted suicide because the elderly person is “done with life.”

Betty Odello, R.N., M.N., a member on Kaiser Permanente’s bioethics committee in Woodland Hills, said she came to the event because she was impressed with the qualification of the speakers. “I wanted a more in-depth analysis of the [California assisted suicide] laws, which I was able to receive.”

Despite the recent legalization of assisted suicide in California, Odello is still hopeful that people can experience a change of heart on the issue. “As long as there’s life there’s hope,” she said. “We’ve got to keep fighting. You can’t give up the good fight.”