When the Trump administration started to systematically separate asylum-seeker families as part of a “zero tolerance” immigration policy at the border just more than a year ago, the objective was to deter people from continuing to seek protection in the U.S.

Carlos, 34, and his son Enrique, 13 (not their real names), had to flee Guatemala at the very same time that this policy was in full effect between May and June of 2018 — and they suffered the brunt of it.

They were separated for more than two months and for most of that time, Carlos didn’t know where his son was.

“I had no intention of leaving my country, where I lived very well by planting and harvesting in season and then buying and selling in the market in Guatemala City,” explained Carlos, a slight man whose soft demeanor turns fierce when thinking about losing his son.

“To think that I left Guatemala because corrupt police threatened my life and my son’s, to come here and have officials take my son away, it’s unbelievable.

“What’s the difference? They were doing the same thing here that they were threatening in my country,” he added during an interview earlier this month in Southern California, where he awaits another court hearing on his asylum application while he and his son stay with a family friend from Guatemala.

In this past year, families like Carlos’s were helped by an army of activists and lawyers who stood up to fight the federal government's policies, and by Church volunteers offering legal and social assistance to thousands of others who have come since.

The need seems overwhelming.

‘Cases take a long time’

In Los Angeles, 18 attorneys work in overdrive at Esperanza Immigrants’ Rights Project, a project of Catholic Charities, where they are still processing and awaiting court dates on the cases of 35 of the families separated last year at the height of the “zero-tolerance” policy.

“The cases are ongoing, we filed asylum applications and are waiting for hearings; most of these cases take a long time,” said Patricia Ortiz, program director for Esperanza. “We have seen the importance of having attorneys, because some of these cases would never make it without one.”

For example, Esperanza’s attorneys took the case of an indigenous woman from Guatemala who had initially been denied her credible fear interview. She had been interviewed in her language, but she was too busy worrying about where her child was to understand the process and what was going on, said Ortiz.

Last year, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and Guadalupe Radio helped raise enough money to fund the work of one attorney and a little bit extra for gift cards for the families, said Ortiz. However, money remains tight.

“We not only have the family separation cases, we have hundreds of other families seeking asylum that we are representing,” said Ortiz. “This crisis hasn’t stopped, and any new rules aren’t going to fix the bigger issue that causes these migrants to leave their country.”

Carlos and his son Enrique, illustrate one of the typical reasons people leave their country, fleeing for their lives: they get targeted by gangs or, in his case, corrupt police.

Carlos had been kidnapped for ransom by members of the Guatemalan National Police that turned up in his small town one evening in May of last year. For two days they beat him up, until he gave up his brother’s phone number so they could call and request money in exchange for his life.

The money, worth a year’s earnings for Carlos, was found among the most affluent wholesalers at the market and taken as a loan by his brother. He was let go, but a couple of weeks later, another request came, this time for more money.

“They said that they would go after my son, who was then 12,” Carlos recalled. “So I told him we were going on an adventure, gathered a little money, and left. My wife and my two small daughters stayed behind. That’s why I can’t publicize my name or my face”.

The trip took a month and at least 12 risky jumps between trains in Mexico. At the border in McAllen, he stepped over the line a few times until he saw Border Patrol agents coming at him. “I wanted to do things legally, and go to them with an asylum request,” he said.

Four hours later, an agent took his son away. Nobody told him where he was going or why. They took Carlos to court in Texas, where he was quickly convicted of illegal border crossing and sentenced to three days in jail. Then he was transferred to Port Isabel Detention Center, where he continuously made requests for information about his son.

“They kept telling me they didn't know. I would answer: ‘How come you didn't know? You took him,’ ” he remembered. “One time an ICE agent told me that it was my fault for doing this and that he was going to be adopted.”

One night at the detention center, Carlos was watching Telemundo when he heard that federal Judge Dana Sabraw had issued an injunction ordering families to be reunited. He figured that his son had to be in one of the children’s shelters, and told a social worker that if his son was not given back to him, he would call the TV station.

“Two days later they released him to me,” he recalled. “I thought I was never going to see him again, that I had come to this country to give my son away.”

They both now live in Riverside, California, in the home of a family friend from Guatemala, while waiting for their court date.

Long road to reunification

Federal authorities have yet to offer a full account of everyone that was arbitrarily separated last year. Further study by the HHS inspector general found that the massive separations did not start in May with the “zero-tolerance” announcement by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, but months before, in the summer of 2017.

Many of them are still separated, particularly dozens of families where the parents were deported and the children stayed behind.

“Did the separated families get relief and justice after Judge Sabraw issued his order?” is the rhetorical question asked by attorney Linda Dakin-Grimm, a pro bono advocate who is representing Carlos and Enrique as part of joint efforts with KIND (Kids in Need of Defense) in Los Angeles.

“My experience is that many families were horribly mistreated and got no semblance of justice,” she answered. “Family separation stopped being the default policy because the judge ordered the government to stop doing it, but it has continued to be the practice they use when they feel like it.”

Department of Homeland Security and Trump administration officials maintain that “zero-tolerance” is no longer the practice, and they have until October to come up with a full accounting of how many families they separated and what happened to them. “Those issues will go back to the judge,” said Dakin.

Recently released figures indicate that the flow of asylum-seekers reached a fever pitch in May of 2019, when more than 144,200 migrants were arrested and taken into custody along the southwestern border, a 32 percent increase from April and the highest monthly total in seven years. President Donald Trump blamed the increase on ending family separations, which he called a “disaster.”

Border Patrol facilities are so overwhelmed that they no longer have the capacity to keep the migrants detained or near the border. In California, it has resulted in hundreds of families being dropped off at bus stops in Coachella, a desert city in San Bernardino County better known for its annual music festival.

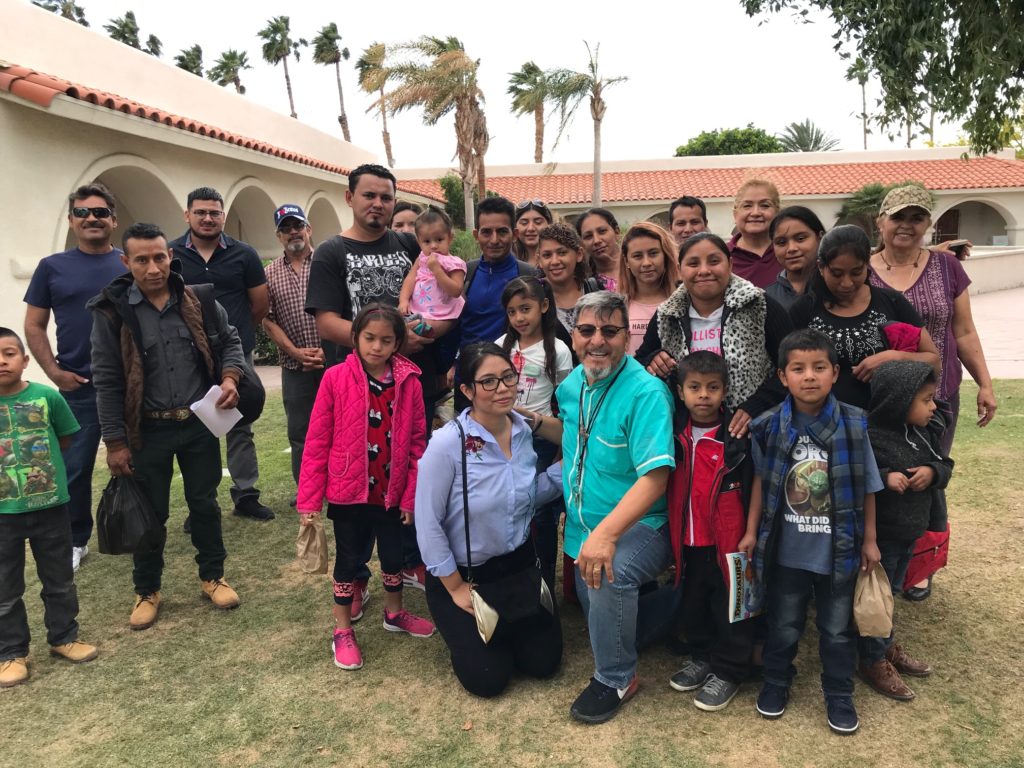

Thanks to a relationship developed with the Diocese of San Bernardino, Border Patrol has been dropping off migrants at Our Lady of Soledad Church in Coachella.

“We are filled to capacity,” explained Father Guy Wilson. “Fortunately, we have an ideal facility called the Valley Missionary Program and we have a dormitory with places to sleep, shower, a large kitchen, rooms to do intake, rooms for children to recreate. This is where many of these families have found transitional help thanks to our many volunteers.”

More than 6,000 people belonging to migrant families in the process of applying for asylum have passed through the parish in the last six months.

John Andrews, director of communications for the San Bernardino Diocese, explained that they get “a place to rest, time to be embraced by the local community of faith, food and clothing, as well as help in getting them to public transportation and to their final destination all over the country.”

It takes about three days for families to transition. But families haven’t stopped coming.

“Right now we have 100 to 200 new people arriving every day,” said Wilson. “We‘ve been able to get money from the state and get many volunteers, but we have money only through the end of this month. We are asking Congressman Raul Ruiz, who represents the area, to find more resources for us, and we are hopeful.”

Pilar Marrero is a journalist who for 25 years has extensively covered the areas of city government, immigration and state and national politics. She works for La Opinión as a senior reporter.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!