Jean Swenson was an ambitious 28-year-old teacher working with at-risk youth in Minneapolis when her life changed forever.

As she drove a car full of teenagers in a drug rehab program back from an outing in 1980, she collided with a semitrailer.

Swenson’s body was thrown into the windshield, the force of which broke her neck. Looking down to see her blood dripping on the floor of the vehicle, she realized that she could not move.

"I kept saying to myself, 'Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will fear no evil, for you are with me,'" Swenson recalled of the painful minutes after the collision.

Swenson said she fell into a deep depression in the months after the accident. She found it difficult to accept that she would never play her piano again, cook for herself or go to the bathroom without assistance.

"I wanted to die. I thought my life was over," Swenson recalled.

Fortunately, physician-assisted suicide was not an option for her, Swenson said in an interview with The Catholic Spirit, newspaper of the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. She is now very grateful to be alive.

But if legislation for people diagnosed with a terminal condition passes the Minnesota Legislature and opens the door to potential expansion to include those with disabilities, assisted suicide could one day be an option for people like her. Such legislation would be a tragedy, said Swenson, who is paralyzed from the neck down.

Canada, for example, now allows those with incurable illnesses or disabilities to take their lives. Some Canadian legislators have proposed including people with mental illness in assisted suicide programs.

"It doesn't stop here, but it expands," Swenson said.

The Minnesota Catholic Conference, which represents the public policy interests of the state's bishops, said in a recent action alert that the proposed End-of-Life Option Act under consideration in the state House and Senate is "one of the most aggressive physician-assisted suicide bills in the country" and violates the teaching of the Catholic Church.

"As Catholics, we are called to uphold human dignity," the conference wrote. "Legalization of assisted suicide works against this principle because death is hastened when it is thought that a person's life no longer has meaning or purpose."

Under the measure, to be eligible for physician-assisted suicide, one must be 18 or older, be diagnosed with a terminal illness and a prognosis of six months or less to live and be mentally capable of making an informed health care decision.

According to the Catholic conference, the measure has no mental health evaluation requirement; no provision for family notification; no safeguards for people with disabilities; and no nurse or doctor is present when the lethal drug is taken, because it is self-administered.

Committees in the Senate and the House must act favorably toward the bill by a March 22 deadline to keep the legislation in play. As of Feb. 27, no additional hearings had been scheduled.

Despite the opposition of pro-life leaders, many physicians, people with disabilities including Swenson and mental health experts, testimony and action taken by the House Health and Finance Policy Committee Jan. 25 appeared to signal that the legislation has momentum.

After a three-hour hearing, the committee passed the bill, which will have to clear other committees before a full vote on the House floor. The House Public Safety Committee, when it meets to discuss it, will decide if the bill will continue its trajectory toward becoming law.

James Hamilton, a resident of St. Paul, has implored legislators to enact the bill before his small-cell lung cancer advances to a stage that will suffocate him.

"Death need not be this ugly. Were the law to allow it, I would choose to end my life before this disease riddles my body and destroys my brain," Hamilton wrote in testimony to the House. "The time and manner of my death should be mine to decide."

Those who oppose the proposed legislation pointed to several concerning aspects of the bill.

The proposal would not require doctors to prescribe a lethal dose of a drug to patients who meet all criteria for it. However, the bill states that doctors who refuse to provide a prescription for the lethal dose are required to refer a patient to a doctor who will.

Dr. Robert Tibesar, a pediatrician and member of St. Agnes Parish in St. Paul, told The Catholic Spirit that he has been watching the proposed legislation and fears it would violate the conscience of ethical doctors.

"To say to someone, 'Well I'm not going to harm you, but I'm going to send you to someone else who is going to harm you,' still goes against our conscience. It still violates our covenant relationship with our patient," said Tibesar, who is president emeritus of the Catholic Medical Association Twin Cities Guild.

Dr. Paul Post, a family medicine doctor who retired in 2019 after 37 years of practicing medicine in Chisago City, testified against the legislation at the hearing and said in an interview that referring patients to a doctor who will kill them is "just as serious" as prescribing the lethal dose.

"If you are making the referral, you are still involved in the act, so that doesn't really take care of your freedom of conscience," he said.

Tibesar and Post also expressed concern about a lack of sufficient mental health checks in the proposed legislation. The bill states that the physician who prescribes the medication is also the one who would refer the patient to a mental health specialist if he or she deems it necessary.

Tibesar suggested this system could allow biased and agenda-driven doctors to disregard signs of concern.

"It would not be a true evaluation of the patient's mental health by an objective, unbiased medical expert in mental health," said Tibesar. "It is just an ... insincere effort to appease people who may have a concern."

Dr. John Mielke, chief medical director at St. Paul-based Presbyterian Homes and Services with more than 40 years of experience caring for the elderly in Minnesota, said at a news conference held by the Minnesota Alliance for Ethical Healthcare before the House hearing that the legislation would "corrupt the physician's ethics" by requiring the doctor to list on the death certificate the underlying diagnosis as the cause of death rather than assisted suicide.

Moreover, the bill would require doctors to determine a six-month-or-less prognosis for the patient to be eligible for assisted suicide. This prognosis, Mielke said, is virtually impossible to accurately determine. Patients outlive a six-month diagnosis in about 17% of cases, he said.

Paul Wojda, an associate professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul who specializes in health care ethics and has been following the issue, said in an interview that if the bill passes into law, there is a risk that doctors who oppose physician-assisted suicide will be terminated from their positions, or not hired, or simply not admitted to medical school.

Unlike Oregeon's assisted suicide law, which served as a model for the proposed Minnesota legislation, no data on the race, age, gender, or self-reported motives would be collected of those who die in Minnesota.

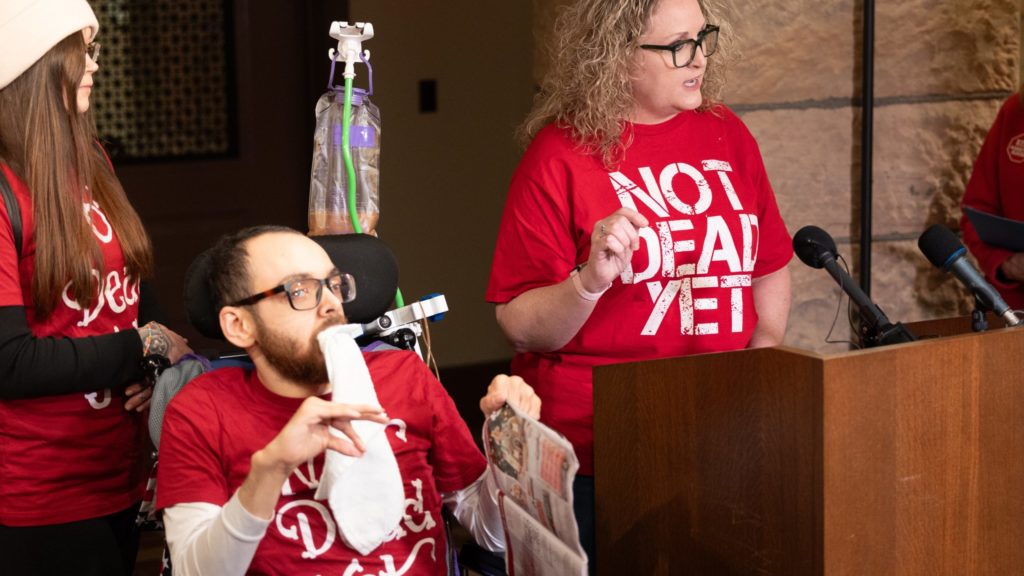

Disability rights activists say that regardless of how the legislation expands, the bill as currently proposed is already working against people who have disabilities.

Kathy Ware -- whose son Kylen has quadriplegic cerebral palsy, epilepsy and autism -- said the proposal invalidates the worth of the lives of those with disabilities. At the Jan. 25 House committee hearing, she advocated for greater resources and home health aides for the disabled, rather than making physician-assisted suicide an option for the terminally ill.