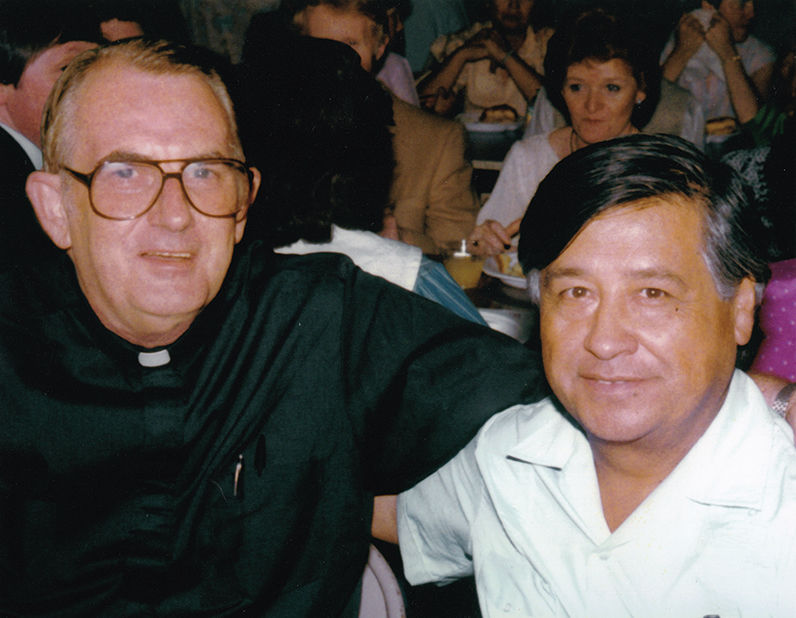

At his former parishes, he is remembered as the friendly, dependable pastor with a gentle Irish brogue who went door to door to introduce himself to the community. But the first thing you see when you enter Msgr. Sean Flanagan’s room at Nazareth House, the home for retired clergy in Culver City, is a large, framed photograph of the priest with Cesar Chavez.

“I was very honored,” says Msgr. Flanagan, beaming in his humble way. “And he was grateful to me because he knew I was very involved.”

Flanagan’s regard for the legendary activist is palpable, and it seems the feeling was mutual. When the parish celebrated Msgr. Flanagan’s 25th anniversary Mass, Chavez traveled all the way to Reseda to serve as lector.

What inspired the legendary civil rights leader to recognize the unassuming pastor?

While assigned to a quiet Westchester parish, a love for history and a desire “to know what makes this great country tick” led the Irish-born priest to nearby Loyola Marymount University, where he pursued a master’s degree in history on his nights off. Having always had a heart for the underdog, he began to study the history of the Church’s involvement in labor movements.

Then one day Msgr. Flanagan received a call from then-Msgr. (now Cardinal) Roger M. Mahony. “I have five bishops over here at the International Hotel and they would like to say Mass there since you are the nearest church,” he remembers Cardinal Mahony telling him.

They turned out to be an ad hoc committee commissioned by the U.S. bishops to mediate between Chavez’ United Farm Workers Organizing Committee and table grape growers in the Coachella Valley after a long and contentious boycott. Suddenly, Msgr. Flanagan’s academic work had spilled over into real life.

A few days later, Msgr. Flanagan recalls, the bishops told him, “We had a breakthrough last night and three of the growers are going to sign with Cesar Chavez and his UFWOC. Would you like to come?”

Msgr. Flanagan got to meet Chavez and many of the key players in the farm labor movement and it inspired him greatly. “I asked my thesis advisor, ‘Could I write about that Cesar Chavez chap?’ He said, ‘It’s already being dealt with quite well. What people would be interested in finding out is why was the Catholic Church [is] gettin’ involved in a labor dispute.’”

Msgr. Flanagan remembers a woman “tackling” one of the bishops after the signing, asking, “Why is the Catholic Church interfering in something that is purely economic?”

“It connected up with the history of the Catholic Church and labor,” he explains. “It went back to ‘Rerum Novarum,’ the encyclical of Pope Leo XIII, which said we cannot just write things. We should be deeply involved with helping people and their causes.” So Msgr. Flanagan didn’t just write a thesis on the Church’s involvement. He became involved himself.

He recalls his first time picketing, when the Teamsters labor union was attempting to take over Chavez’ movement. “I went out there in my black suit and collar carrying a sign ‘Teamsters Unfair on Farm Workers.’ I had a rabbi in front of me and a Quaker lady at the back of me. And we had more fun,” he says with a twinkle.

While an associate, he took part in some two-dozen pickets and made regular trips to Coachella Valley and Delano to visit the farm workers, all while keeping up with his obligations in the parish. “I was in the picket line up in Fresno and Holy Week was comin’ up. My pastor said, ‘I need you back.’ And I missed the opportunity of bein’ arrested with Dorothy Day,” he laments.

It was Chavez’ legendary fasts that earned him Msgr. Flanagan’s deepest admiration. He recalls being there for the 22nd day of one of the fasts, which were Chavez’ peaceful response to violence and injustice, inspired both by Gandhi and his devout Catholic faith.

“I was up on the stage lookin’ down at him in the front row and every half minute kind of a seizure would cross his face and he would wince in pain — real pain. And there were people sayin,’ ‘Oh, he’s only pretendin’ to fast.’ Anyone who saw his face like I did … it was real pain. I think it was the next day the doctor said, ‘Enough,’ y’know, ‘you are goin’ to kill yourself.’”

Meanwhile, Msgr. Flanagan was gaining a reputation for social action. He was invited to join a committee of priests who supported the farm workers and was asked to brief the priests’ council on the progress of the movement.

After nine years with the movement, Msgr. Flanagan was assigned pastor for the first time, at St. Catherine of Siena in Reseda. Though he didn’t have time for any more trips up north, he never lost his heart for the underdog.

“The biggest change when Msgr. Sean came,” remembers St. Catherine’s parishioner Jean Brown, “was starting the Spanish Masses.”

“Before we had Spanish Masses, all the Hispanics in the area went to other churches where they had [Spanish] services,” says Deacon Pedro Lira, whom Msgr. Flanagan brought in to help with the growing Spanish-speaking population.

“I became more and more aware that there was far more Hispanics in the neighborhood than I had imagined,” he recalls. After starting a Spanish Mass on Saturday night, he moved it to a prime slot on Sunday morning.

“That huge church, which holds a thousand people, quickly filled up and one Mass was not enough. I had to put a second,” he says.

“Msgr. Sean opened the door for us,” says Bertha Morquecho, who also worked with Flanagan. He formed a Hispanic committee and initiated scores of Hispanic ministries. Then he brought in the parish’s first Hispanic priest.

“Father Sean asked me if I knew Father Raul Cortes, and I said, ‘Yes of course,’ because he was the first Spanish-speaking priest in the valley,” says Morquecho. “Msgr. Sean wanted to get someone the community knew. Then even more people started coming because Father Raul was here.”

Father Cortes died in August of last year, after 21 years in the parish.

According to newly-ordained priest Father Ethan Southard, whose home parish is St. Catherine’s, Cortes and Flanagan sowed the seeds that made his vocation possible.

“Cesar Chavez said that to be a man is to suffer for others. That’s what I saw in Father Raul and Msgr. Sean that inspired me. They were involved with the suffering of others to the point of suffering themselves.”

At Southard’s ordination reception June 4, Cardinal Mahony recalled his history with Msgr. Flanagan in a recorded greeting.

“My first contact with you had to do with the farm labor conflict. … People who were powerless and in many ways being exploited for their labor were the people dearest to your heart. That spirit of yours continued to increase over the years and you always stayed very close to the farm workers’ movement,” the cardinal said.

“We had many opportunities to share in that work. At your parish of St. Catherine of Siena, you were also a great advocate for the Spanish-speaking and all migrants and immigrants. Jesus was always found with the ‘wrong people’ — the poor, the lepers, the tax collectors — and that’s where you were found as well.”

“He was a real pastor priest,” says Brown, a former parishioner, “a pastor to everyone.”