ROME — To grasp the depth of Chile’s clerical sexual abuse crisis, imagine if around 68 of the United States’ 255 active Catholic bishops had been subpoenaed by civil prosecutors on suspicions of either committing the abuse of a minor, covering it up, or both.

That’s the situation in Chile, where nine of 34 bishops (27 percent) have been subpoenaed, including Cardinals Francisco Javier Errazuriz and Ricardo Ezzati, both former and current archbishops of Santiago, respectively. Errazuriz is also a former member of the council of cardinals that has been advising Pope Francis on Vatican reform.

Ezzati’s resignation was accepted by the pope March 23. The 77-year-old faces not only accusations of abuse cover-up, but is also the target of a $500,000 lawsuit involving an alleged rape at a residence in his cathedral that Ezzati allegedly failed to report.

Ezzati was replaced by Bishop Celestino Aós Bracco, who’s been appointed as apostolic administrator, meaning he’s not the new archbishop, and who himself has a troubled history on the abuse crisis.

The pontiff is having trouble finding a permanent replacement, much as he did when he replaced the other eight bishops whose resignations he accepted after last May, when every Chilean prelate offered his resignation to Francis when he summoned them to Rome. Each bishop was replaced by an apostolic administrator, rather than by a permanent replacement.

Former seminarians of the Diocese of Valparaiso have accused Aós of negligence when he dealt with allegations against five priests during his term there as the promoter of justice. Aós deemed the accusations unsubstantiated in 2012, but today one of the accused has been removed from the priesthood and the others are being investigated.

Defenders note that Aós was a priest when he handled these cases, not a bishop, under the direct authority of Bishop Gonzalo Duarte, who had his resignation accepted by the pope last year and who’s been accused of cover-up and also of abuse of power and conscience.

Three days after Aós took possession of the archdiocese, a civil court ruled that the Church of Santiago had to compensate three of Karadima’s victims for an institutional cover-up of his crimes. Aós released a statement saying the Church would not appeal.

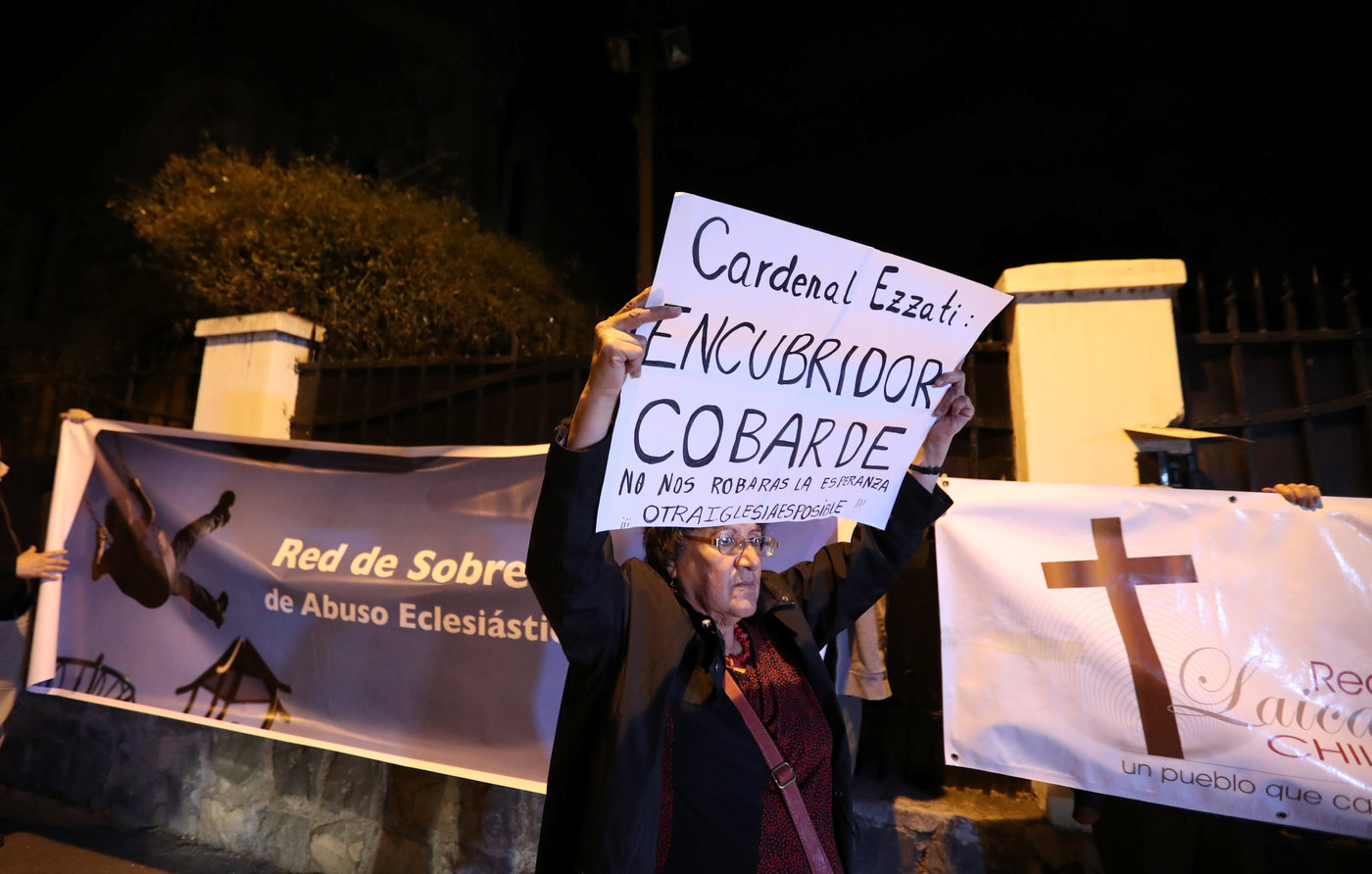

Outside Chilean Cardinal Ricardo Ezzati’s residence in Santiago, a demonstrator displays a banner during a rally over allegations Ezzati covered up sexual abuse of minors. The banner reads: “Cardinal Ezzati: Coward covering up! They will not steal our hope. Another church is possible,” and “Survivors Network of Ecclesiastical Abuse.” (CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE/IVAN ALVARADO, REUTERS)

Among the eight bishops who had their resignations accepted by Francis is Bishop Juan Barros, former prelate of the southern Diocese of Osorno.

He’d long been accused by victims of covering up for Fernando Karadima, Chile’s most infamous abusive priest, who was removed from the clerical state last year, after being sanctioned by the Vatican to a “life of penitence and prayer” back in 2011.

“I recognize and I want you to communicate this accurately, that I have made serious errors of judgment and perception of the situation, especially due to lack of truthful and balanced information,” Francis wrote in a letter to the Chilean bishops last April.

A month later he wrote the bishops again, accusing Chilean bishops of various crimes related to the abuse crisis. The pope also said that replacing members of the hierarchy was a necessary step, but not sufficient.

The scope and depth of the crisis, many in Chile have argued, makes the resignations of Barros, Ezzati, and others, while “keenly expected,” also “almost an accessory.”

The explosion of the crisis happened roughly a year ago, after Francis’ visit to the country and his decision to send two senior officials to look into “the Barros case.”

Francis had transferred Barros to a southern diocese in 2015, and protests about his role in backing Karadima were immediate. Victims spoke with anyone who would listen, including members of the pope’s own Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors.

The media, both in Chile and in Rome, kept the case in the spotlight. Chilean politicians sent a letter to the pope asking him to change course, and even some bishops spoke up.

But Francis kept going, full steam ahead, until the evidence of the iceberg became too visible to ignore and he swiftly changed course.

In the words of a Chilean priest who’s a clerical abuse survivor, “The Church is now battered and banged up. Some days, it feels like we’re fighting the advance of the water with buckets. And it’s not only in Chile, it’s everywhere: Australia, France, the United States (where 12 state attorneys general are investigating local Catholic dioceses).

“But the Church is not the Titanic; it won’t sink,” he said. “It’s on all of us, however, to work to make sure it does more than stay afloat.”

Inés San Martín is an Argentinian journalist and Rome bureau chief for Crux. She is a frequent contributor to the print edition of Angelus and, through an exclusive content-sharing arrangement with Crux, provides news and analysis to Angelus.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!