Statues of Confederate generals brought down or repositioned. McSherry Hall at Georgetown University renamed because Father William McSherry sold slaves.

What’s in a name? What’s in a statue? Are California’s 585 mission bells along the road next in this flurry of reassessment of representational history that includes aggrieved people, questions about the nature of art, and a selective rendering of what took place long ago?

What, exactly, is a symbol and what force — moral, spiritual, or otherwise — does it have?

Californians take pride in the weathered old bells on their staffs spaced along U.S. Route 101 and offshoot roads taken by original padres. When I was a child, my heart quickened at their sight, for it meant my parents and us kids were on the road and would soon be taking in a mission or two on our way to the mountains, the beach, the desert, or Lake Tahoe.

Spotting the road bells meant inner joy, as it did later for my wife and our kids. Even as we age, I hear those bells inside when I pass and my heart is glad.

But for some, that bell on the road is an insult, and echoes with something akin to Julius Caesar’s infamous summary of laying waste to Gaul: “I came. I saw. I conquered.”

To Valentin Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band near Gilroy, those bells mean, as he put it, “We conquered you, we controlled you, we destroyed you.” And since the missions and their bells were erected by the Spanish Franciscans, there’s no mistaking who Lopez accuses: the followers of St. Francis of Assisi. So much for talking to animals, right?

After many years of trying, in June of this year Lopez was able to get one bell removed from the University of California Santa Cruz campus.

But what of Mission San Luis Rey, where several hundred Luiseno Indians ran into the water off Oceanside to beg Father Peyri not to go back to Spain as he boarded a ship, but to stay with them where he had served them for three prosperous and peaceful decades?

What of St. Junípero Serra’s death at Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Carmel, where 600 Esselen and Rumsen Costanoan Indians fell weeping, many cutting off talismans from his robe and even his hair?

What of that all-Indian orchestra at Mission San Antonio that played original works? Were those performed without pride or joy? Were the Indian singers at Carmel whom the celebrated author Robert Louis Stevenson said sang in 1879 with such profundity merely faking it? Was there no music in those bells?

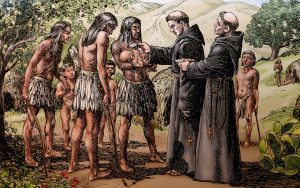

A baptism conducted by California mission friars is shown in a sketch displayed at the Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcala in San Diego. This drawing is part of a collection of sketches depicting mission life by California artists A.B. Dodge and Alexander Harmer. (NANCY WIECHEC/CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE)

In a June ceremony, California Gov. Gavin Newsom apologized to the state’s 600,000 Native Americans at a June ceremony, calling what happened to their ancestors in the takeover by Europeans “genocide.” Undoubtedly it was. And shameful. But who was responsible for it — the Spaniards or the Americans?

To understand the legacy of the bells, that and other questions need to be answered. The role that microbes of infection played in this tragedy, for example, must be understood.

The treatment of Indians by the Franciscans, a source of many accusations against the Spaniards, must be examined with context and a careful attention to statistics. And the good works, especially those of radical mercy, of Serra and the Franciscans cannot be ignored.

Who committed genocide?

On the question of genocide there is no less an authority than James Sandos, Ph.D., Farquhar Professor of the American Southwest at the University of Redlands. In 2010, he told a large gathering of mostly Native Americans at the California Indian Conference in Irvine that the “comparison [of Franciscan acts] to genocide is totally false.”

The true culprit? “The U.S. government paying people to slaughter others, that’s genocide,” Sandos said at the event. On the same panel with Sandos was reputable mission-era historian George Harwood Phillips, Ph.D., who agreed: “I don’t think you can see Franciscan missionaries committing genocide [in California].”

Neither of these distinguished scholars are mission apologists; in fact, they are critical of several practices in the missions. I was in the audience, heard them both, and can attest that no one in the crowd of mostly Native Americans opposed them.

Regarding genocide, there are two crucial elements to look at: intentionality and magnitude.

Did the Spaniards intend to wipe out California’s Indians? The answer to this question is a simple no.

What about the magnitude of losses? There were an estimated 225,000 Indians in California in 1769. In 1830, just prior to secularization of the missions, there were about 150,000, a drop of one-third.

The vast majority of this admittedly tragic decline was due to infectious diseases that the Spaniards had no control of — they hardly understood how pathogens spread. And tribes also suffered from the trampling of native food sources when settler cattle came.

Nor were there any real massacres by the Spaniards along the West Coast. And there’s a major spiritual reason for that: The Spaniards, and the Franciscans in particular, saw the Indians as having an inviolate soul, of being essentially the equal of any Spaniard.

Unlike the Puritans of New England, for instance, the Spanish intermarried with Native Americans almost from the start; in fact, Serra actively encouraged it.

Perhaps some of the understandable anger toward the Spanish stem from two very real records of atrocity: that of Spain 200 years earlier during the conquest of Peru and Mexico, as well as modern-day Arizona and Florida, in which scores of Native Americans were killed. The other “black record” is that of the United States when it took over California in 1850.

I am convinced that the Spanish (particularly the Franciscans) learned an important lesson over those 200 years of the colonial conquests, and that they put into practice in their last crucible, California: You do not convert someone by force.

As Viceroy Antonio Bucareli in Mexico City instructed the new governor of California, Felipe de Neve, in 1776, “The good treatment of the Indians and the kindness, love and gifts showered upon them are the only means, taken together, to win them over; and may Your Grace prefer those means to others that stem from rigor. By the latter we have never been able to win good will from anyone.”

That’s a far cry from the blunt words of the first American governor of California, Peter Hardeman Burnett, nearly a century later: “It is inevitable that the Indian must go.”

That suggests genocide, which climaxed in the last stand of California’s Native Americans in the Modoc War of 1872.

By then, the number of California Indians had declined to just 30,000, an 80 percent drop after the Spanish withdrawal and nearly three times the rate of loss under the Spaniards. And 40 percent of those losses under the Americans was not due to disease, but outright murder.

One important point to keep in mind is that the large majority of California Indians did not come into the missions. The largest mission population was 22,000; that is about 10 percent of the population estimate on contact of 225,000.

On several occasions, Serra referred to the California Indians being “in their own country.” He almost never referred to Indians as “barbaros” (“barbarians”), as others did, but rather “indios,” “gentiles,” or “pobres.”

In fact, Serra directly suggested that Spain remove itself from California if soldier depredations continued. If the better side of Christianity was not shown the Indians on a daily basis, he said, “what business have we … in such a place?”

The bell tower of St. Peter's, Serra's childhood parish church, in Petra, Mallorca. (DINA MOORE BOWDEN VIA GREGORY ORFALEA)

Were the missions slavery?

The question arises: Were the missions slavery? It’s a serious claim, but it is false. No one was forced into the missions.

This is made clear by the testimony of Father Pedro Font, diarist of the second settler expedition into Upper California, who observed, “The method of which the fathers observe in the conversion [of the Indians] is not to oblige anyone to become Christian, admitting only those who voluntarily offer themselves for baptism.” Most historians ratify this.

There was, however, a catch. Once one entered the mission he or she could not leave without permission. The missions were a community on a frontier and Indian labor, as well as Spanish labor, were necessities for a community’s survival.

We might ponder how many who came into the mission system understood this quid pro quo, but there’s little doubt most fell to the task of contributing their labor for the food, clothes, living quarters, and other items they were given.

Douglas Monroy, a Hispanic-American historian and author of “The Borders Within,” calls this “the communitarian spirit,” and he notes that working for the common good was not all that different from the ethic of the Indian village. Sandos calls the mission Indian status “spiritual debt peonage,” though the Indians were given concrete things, not just spiritual practices.

Most took “leave” to their home villages for weeks or months. Some, like the Luiseno of Mission San Luis Rey, were already in their villages and commuting to mission work.

There is one undeniable, hard, and premeditated thing to admit about the missions: the use of the flog for corporal punishment for theft, assault, concubinage, and desertion. That Spanish civilians and soldiers got the same treatment is no comfort for those of us who see such a thing as abhorrent.

However, a few things need to be said about this practice. First, whippings for discipline were common in the 18th century. Even schoolboys at Eton in England were caned for infractions, and their parents paid a fee for it to the school.

Second, many tribes made prisoners of war run a gauntlet of beatings, so such a thing was not entirely strange.

Third, as Father Francis Guest has written, the Indians were considered children by the padres, and as such the flogging was cut in half (12 strokes at most). Guest also notes that the punishment was not to be given in anger and if it were, those who did so had committed a grave sin and were subject to punishment themselves.

Serra himself was clearly conflicted about the practice: “I am willing to admit that in the infliction of punishment we are now discussing, there may have been inequities and excesses on the part of some Fathers and that we are all exposed to err in that record,” he wrote.

About this matter, I wrote in my biography of Serra, “Journey to the Sun: Junípero Serra’s Dream and the Founding of California” (Scribner, 2014), in no uncertain terms: “It was cruel, a violation of the Fifth Commandment; Christ accepted the Roman soldier’s whipping his body, but he certainly didn’t recommend it. Serra’s and Lasuen’s arguments for flogging ultimately ring hollow. They should have had the wisdom and foresight to stop it.”

Ultimately, before the mission period was over, the flogging was outlawed in 1833. Father Francisco Diego at Mission Santa Clara applauded that “such punishment as revolts my soul is being abolished.”

If this were the main story of Serra and the missions, I would say tear down the bells. But it isn’t, not by a long shot.

In his landmark apology to the native peoples of the Americas in Bolivia in 2015, Pope Francis said, “Where there was sin — and there was plenty of sin — there was also abundant grace increased by the men and women who defended indigenous peoples.”

As I have indicated, Serra tirelessly defended the indigenous people against those who talked as if they were subhuman, with no dignity, who abused them sexually, and grabbed their land.

But the supreme act of “radical mercy” occurred after the Kumeyaay raid on Mission San Diego in 1775 that burned the mission to the ground and killed three Spaniards, including a priest friend of Serra’s who was one of the Kumeyaay’s greatest champions, Father Luis Jayme.

Despite Jayme’s deeply tragic, nonsensical murder (he was beaten to death and skewered by a dozen arrows), Serra insisted to the viceroy that those jailed and awaiting execution in San Diego for the attack be pardoned and released.

“As to the killer,” Serra appealed to the highest authority in the Americas, “let him live so that he can be saved, for that is the purpose of our coming here and its sole justification.”

The fountain and bells at Mission San Juan Capistrano. (WIKIMEDIA COMMONS)

Though there was severe loss of life due to disease, and disciplinary measures we do not counsel today, in contradistinction to intentional murder and land seizure of the American government in the 19th century, those Hispanic mission bells represent the Gospel of Love. That, to me, is one California symbol worth saving in the midst of so many social ills that inflict so much misery.

The Franciscans were founded, after all, by one of the great peace-lovers of all time; if they had forgotten him in Peru and Mexico and Arizona, they did not — for the most part — forget St. Francis in California.

An early San Diego interlude in the life of Serra always brings to me the essential benevolence of the Franciscans in 18th-century California. On the first exploration, just over the present-day U.S.-Mexico border in what is today the Tijuana Estuary Nature Preserve, the Portola expedition came across “good sweet water” and the leader proposed to water the horses, let the men bathe, wash their clothes, and drink.

Serra would have none of it.

“We do not want to spoil the watering site for the poor gentiles,” he said, meaning this was the Indians’ water and hands off. Does that sound like genocide?

On the side of the heart

“If we weren’t here, who would have put the bricks on top of each other?”

Mel Vernon, captain of the Luiseno tribe, hardly sees mission life uncritically. But at a book signing for my biography of Serra in San Diego, he took the time to shake my hand and tell how proud he was to be a part of the book.

Vernon is one of the many Native Americans in California who understand this complex history and come down on the side of the heart.

Ernestine de Soto, whose mother was the last Native American speaker of Chumash, herself a Chumash shaman and registered nurse, is no shrinking violet on difficulties in the missions, as I can personally attest. Yet today she is not only a devout Catholic, but leads winter solstice services at Mission Santa Barbara with a recitation of the “Our Father” in Chumash.

She also wrote to the Vatican presenting evidence of a second miracle for Serra sainthood considerations — her own daughter’s miraculous deathbed recovery from cryptogenic pneumonia.

There’s archaeologist Ruben Mendoza, Ph.D., of both Yaqui Indian and Hispanic descent, whose father hated the Church and the missions and grew up with the same hatred, refusing to make a fourth-grade mission model as a child. (Instead, the young Mendoza made a model of Aztec pyramids.)

Mendoza, chair of the School of Social, Behavioral and Global Studies at California State University at Monterey Bay, had three transformative experiences while excavating missions, the last at Mission San Luis Bautista that led to other discoveries convincing him that at least 13 missions “were precisely oriented … to capture illuminations, some of days that would have been sacred to Native Americans.”

In 2015, Mendoza flew from California to attend the Serra canonization ceremony with Francis in Washington, D.C., the first time ever a pope has done such a thing on American soil.

Left to right: St. Junípero Serra scholars Steven Hackel, Robert Senkewicz, Rose Marie Beebe, Ruben Mendoza, and Gregory Orfalea at Serra's canonization in Washington, D.C., in 2015. (GREGORY ORFALEA)

Andy Galvan, the Ohlone-Patwin-Bay Miwok director of Mission San Francisco Dolores, was at the canonization ceremony, too. Galvan is no blind observer of mission life, nor of Serra’s flaws, but an enthusiastic supporter of his inspired life and those of other Franciscans who served selflessly.

In my research of more than 12 years, I discovered records of 200 interview contacts with descendants of mission days in the 1940s that culminated in 50 taped testimonies in 1949 in Monterey, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Many of these had relatives who lived in the missions and even knew Serra, and dozens of them were Native American or mestizo.

Several mentioned a practice dating back to the days just after Serra died when Esselen and Rumsen fishermen would lay tobacco and other offerings at a point in the Carmel River, praying to Serra for a good catch.