A progressive town known for its impressive institutions devoted to philanthropy and intellectual development, the city of Philadelphia made a surprising move in 1879: it cut all city funding for the poor, leaving the city’s neediest to depend solely on institutions.

The reason? The Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity believed that charity should not extend beyond institutional work; giving money or food to the poor directly was too risky. Anything that wasn’t carefully monitored, the thinking went, simply encouraged the poor to be lazy.

Unfortunately, this was not a passing trend. The idea that charity, and by extension, the poor, were a drain on public resources became popular across America, and continued well into the 20th century.

Cities reworked their charitable programs to take away any autonomy the poor had. Intellectuals fussed over the fecundity of the poor that threatened to outnumber the white upper class. Politicians worked to pass immigration legislation that would keep out everyone except who they saw as the most desirable.

In 1922, an article by John C. Duvall in The Birth Control Review decried support for the poor, arguing that they should be treated like livestock: “This situation prevails chiefly because of a sentimental refusal to interfere with the course of nature and apply to mankind our knowledge of the same biological laws which have allowed us to produce grafted fruits, prize bulldogs, and a superior quality of roast pork.”

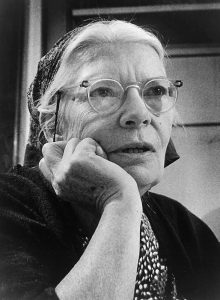

The was the society that a woman named Dorothy Day grew up in. A political radical in her young adult years, she worked as a journalist for a socialist paper in New York City, writing on the problems the working class faced.

She participated in a suffragette hunger strike. In her 20s, she converted to Catholicism, co-founded a Catholic newspaper devoted to labor issues, worked as a social activist, and lived a life of voluntary poverty among the poor. Today, the Catholic Church is considering her cause for sainthood.

One of her most radical ideas was one that might seem very simple to us now. Day believed that every person was worthy of love and assistance, with no exceptions. In a country that largely regarded the poor as biologically inferior, this was revolutionary and countercultural.

Intellectual circles at the time were dominated by the so-called “scientific charity” and eugenics movements. These fostered the belief that, as social historian Brent Ruswick said, “the pauper could not be rehabilitated, only suppressed.” Charity work, then, became a matter of figuring out who was “worthy” of relief, a question of “science” rather than of love.

When Day was born in 1897, scientific charity workers sought to find an objective, analytical way to distinguish between those who were impoverished because of bad fortune, and those who were a part of a “degenerate” class and therefore “unworthy” of charitable relief. Their method relied on the personal judgment of charity workers and skewed statistics.

As Day was coming of age, the conclusions morphed into the new eugenics movement. A pseudoscience based on the belief in a “degenerate” class, eugenicists theorized that almost all character traits are inherited, and that a person’s success was the result of good genes rather than environment or resources.

The poor, therefore, were impossible to help, as their genes dictated their situation.

The newest fad adopted by a surprisingly diverse coalition of scientists and intellectuals, progressives and conservatives, as well as doctors and even charity workers, eugenics would become an incredibly strong force in American politics, spawning anti-immigration legislation and statutes that allowed the state to forcibly sterilize people they deemed “unfit.” Disregard for the poor was becoming policy.

In Day’s time, then, Americans were more likely to see the poor as a nuisance to be tolerated rather than people to be helped, to be institutionalized rather than assisted. “Too often the attitude is that these are the ‘unworthy’ poor,” she wrote in the Catholic Worker in 1937. “The attitude is ‘You can’t do anything with them, so why feed them?’ ”

Degeneracy theory and eugenic ideas, as strange as they seem to modern readers, were part of the air that Day breathed. A college textbook published in 1918, the year she turned 21, stressed the importance of “the need for as perfect a correlation as possible between income and eugenic worth.”

It also instructed the reader that “the idea of giving every man a wage sufficient to support a family can not be considered eugenic. … Eugenically, teaching methods of birth control to the married unskilled laborer is a sounder way of solving his problems than subsidizing him so he can support a family.”

For Day, poverty had been treated as a fault as long as she could remember.

Day wrote in her autobiography, “The Long Loneliness”: “From my earliest remembrance the destitute were always looked upon as the shiftless, the worthless, those without talent of any kind. … They were that way because of their own fault. They chose their lot. They drank. They were the prodigal sons who were eating the swines’ husks only because they had squandered their inheritance.”

Her words here are carefully chosen. “Shiftlessness” was a pet diagnosis for eugenicists, a catchall term to help diagnose the degenerate.

In his book “War Against the Weak,” journalist Edwin Black writes that eugenicists understood “shiftlessness” as “the genetic defect of being worthless and unattached to life,” and quotes one eugenics textbook that defined the word “shiftless” as a “genuine genetic trait.”

It was a lot easier to blame bad conditions on the “shiftlessness” of the poor than it was to fix the conditions themselves, conditions that were, more often than not, the fault of a society that catered to the rich and successful.

Clearly, charity organizers and eugenicists weren’t thinking in terms of charity or even social responsibility. They were looking at poor individuals from a “scientific” perspective, and their language about the poor reflected that. Many charity organizers used metaphors implying that the poor were a disease or parasites leeching off government assistance.

Oscar McCulloch, one of the leaders of the scientific charity movement, described a “pauper” as someone whose “self-help has given place to a parasitic life” and who, even worse, might beget “children who are after his own kind, recruiting armies of vice.”

Day didn’t buy any of this. She saw these categories and statistics for what they were — excuses that upper-class people made so they could control the symptoms of poverty while ignoring causes. And she understood what scientific-charity advocates and eugenicists could never figure out: that she was able to stay afloat in hard times, “because of my friends, my background, my education, my privilege.”

Even before she converted, Dorothy never dehumanized the poor, instead always recognizing that they were people in need of assistance. After her conversion, whe wondered to herself: “Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just minister to the slaves but to do away with slavery?”

Day explains in “The Long Loneliness” that she ended up joining the Catholic Church not because she had been swayed by theological arguments or even by its social teachings (which she was unaware of at the time), but because it was where she felt the poor were: “It was the great mass of the poor, the workers, who were the Catholics in the country, and this fact in itself drew me to the Church.”

Joining the Church didn’t give Day immediate or easy answers to her questions. She was often frustrated with her feeling that Catholics tended to be content defending the status quo. But she prayed that God would show her how to use her talents for “my fellow workers, for the poor.”

God answered her prayer by showing her that the virtue of charity did not have to be a systematic decision about the worthiness of a person. It didn’t have to be a grudging handout to a “degenerate.”

Instead, she was realizing, charity is a recognition of both a person’s dignity and the personal response that this dignity should inspire.

Hers was also a recognition that the world needed more than political action. It needed a true understanding of charity, from which personal responsibility for the entire human family would flow. “[W]e must act personally, at a personal sacrifice…” she wrote, “to combat the growing tendency to let the State take the job which Our Lord Himself gave us to do.”

Now she could love each person as an individual. She could advocate for them and also live her everyday life for them. Without Catholicism, she had never understood how to live out a love so radical. Now that she was one with the poor, she was able to experience authentic charity, charity that was personal rather than en masse.

She could understand charity, because she did not see the poor as genetic defects, weakening the race by reproducing. She didn’t see them as leeches on the government or a disease to society.

Instead, she saw persons. She saw the infinite, unique, complex reasons why these individuals were in situations where they needed help.

She saw the workers who couldn’t make enough to support families. She saw those on welfare who were patronized and pitied. She saw those with disabilities struggling to get by in a society that acted like they didn’t exist.

She saw the women struggling to keep jobs in workplaces that ignored the demands of pregnancy and childbirth. She saw those who just needed some extra help to get back on their feet. She saw those who were never going to change their ways.

She saw that all people deserve love and care, simply because they are a part of the human family. No one is degenerate, no one is unworthy.

Today, talk about seeing the dignity of every person no longer seems so radical. Perhaps that it is in part thanks to people like Dorothy Day who worked so quietly but effectively to transform the culture. May we follow in her footsteps, and continue to serve all, regardless of their perceived worthiness or utility.