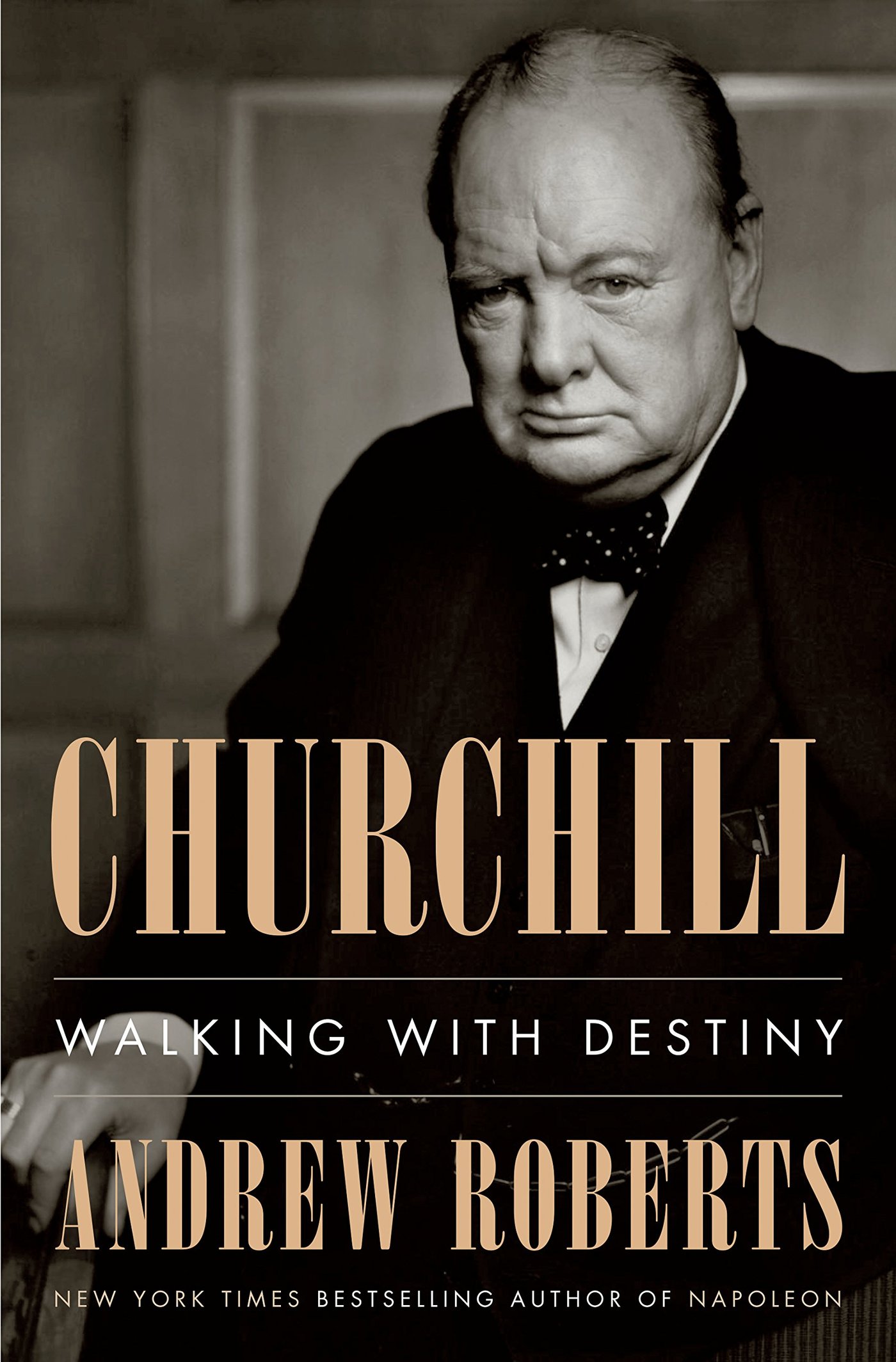

In “Churchill: Walking with Destiny,” Andrew Roberts provides an appreciative and definitive biography of the man.

In these tumultuous times, Winston Churchill’s life contains many lessons for us today as we struggle with the ups and downs of contemporary social, political, and religious life.

The first lesson of Churchill’s life is that serious parental failures do not necessarily destroy our potential for greatness. Winston’s father, Randolph, treated his son with disdain, repeatedly telling the young boy and later the young man that he would never amount to anything.

Winston’s mother, Jennie, had numerous extramarital affairs and spent much more time and energy as a social butterfly than as a caring mother. Both parents neglected their son terribly. Sent away to boarding school, young Winston sent 76 letters to his parents who sent only six in return. The boy begged to spend Christmas with them, but was rebuffed. Despite these parental failures and their bad example, Churchill himself was a faithful husband, loving father, and a world historical figure.

A second lesson to be learned from Churchill is the majority does not determine the truth. Winston spoke against appeasement of Adolf Hitler, bucking the opinion of the most powerful and influential people in England. After Hitler conquered Belgium and France, many within the British establishment sought to make peace with Hitler. But Churchill stood his ground.

He insisted that Hitler’s promises were worthless and that giving in to the German dictator would lead to the subjugation of the British people. Only after Hitler invaded Poland did it become clear to everyone that Churchill was right. As Archbishop Fulton Sheen once wrote, the truth does not depend on a majority vote, “Wrong is wrong, even if everybody is wrong. Right is right, even if nobody is right.”

Third, Churchill believed that the Almighty had a plan for his life, that he was “walking with destiny.” As a teenager, he told a friend that he would “save London” and indeed Britain itself from invasion. His whole life he viewed as a preparation for this mission. Churchill found what the late, great theologian Germain Grisez called, a “personal vocation.” Churchill embraced this calling to save the British people, indeed more than the British people, with his entire vigor, strength, and commitment.

Fourth, Churchill accomplished his God-given mission despite personal setbacks of every kind. A fall sustained in youth led to a permanent shoulder injury. His military acumen was forever afterward questioned because of his failed Dardanelles campaign. He lost three parliamentary elections. Early in World War II, when he had first become prime minister, the Axis won battle after battle and appeared unstoppable. Churchill experienced family distress on account of his son’s drinking and failed marriage.

After winning World War II, Churchill lost his position as prime minister. His wife, Clementine, tried to comfort him: “It may well be a blessing in disguise.” Churchill replied, “At the moment it seems quite effectively disguised.” Despite all these setbacks, and many more, Churchill continued to serve his country with distinction. “If you are going through hell,” he wrote, “keep going.”

Fifth, Churchill’s life teaches us that our imperfections, misjudgments, and errors need not undermine our God-given mission. Churchill could easily have given up hope of ever doing anything worthwhile. He made many blunders, like supporting the gold standard, siding with King Edward VIII during the abdication crisis, underestimating the strength of Japan’s military, and believing, to a degree, the lies of Stalin.

“I should have made nothing if I had not made mistakes,” said Churchill. But these mistakes partially made him. From each mistake he learned, and no mistake shook his ultimate resolve. Toward the end of World War II, someone asked him if the Allies would deal with the defeated Germans as they did in the disastrous Versailles treaty after World War I. He answered, “I’m sure the mistakes of that time will not be repeated. We shall probably make another set of mistakes.”

Biographer Andrew Roberts points out many instances in which Churchill’s blunders ended up helping him in the long-term, exemplifying thereby the insight of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will.”

Sixth, Churchill loved his friends. Throughout his life, he made friends with aristocrats as well as with the common born. His lifelong friends included those with whom he disagreed politically and religiously, as well as those who saw the world as he did. Although he greatly disagreed with Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler, as prime minister Churchill treated Chamberlain with great kindness, even having him take up important governmental positions in Churchill’s administration.

Seventh, Churchill was not afraid to see the complexity of a situation or the complexity within a single person. Take Churchill’s description of Stalin: “His weapon logic; his mood opportunist. His sympathies cold and wide as the Arctic Ocean; his hatreds tight as the hangman’s noose. His purpose to save the world: his method to blow it up. Absolute principles, but readiness to change them. Apt at once to kill or learn: dooms and afterthoughts: ruffianism and philanthropy. But a good husband; a gentle guest; happy, his biographers assure us, to wash up the dishes or dandle the baby.”

Churchill did not fall into simplistic black and white thinking, though he likewise did not deny that black is black and white is white. Seeing the complexities within each human heart helped Churchill resist the temptation to seek revenge against his enemies. “In world affairs, it is no use indulging in hate and revenge. They are the most expensive and futile and self-destroying luxuries by which one can squander the treasure accumulated by the valour of your sons and daughters.”

Finally, and perhaps most spectacularly, Churchill embodied courage. We “must be judged in the testing moments of their lives,” he wrote. “Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities because … it is the quality which guarantees all others.” Churchill embodied physical courage of a heroic degree in escaping from a prisoner of war camp as a young man and in the many battles he fought during various wars. Most of all, Churchill had moral courage that enabled him to lead his people to stand up to Nazi aggression and to the Iron Curtain of Communism.

He wrote, “Never give in. Never give in. Never, never, never, never — in nothing, great or small, large or petty — never give in, except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force. Never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.” And he wrote, “Success is not final. Failure is not final. It is the courage to continue that counts.” That is a lesson for all seasons, including our own.

Christopher Kaczor is professor of Philosophy at Loyola Marymount University and the author of several books, including “The Seven Big Myths about the Catholic Church.”

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis, and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!