“How ingenious an animal is a snail…. When it falls in with a bad neighbor it takes up its house, and moves off.”

— Philemon, 3rd or 4th century B.C. Athenian poet

Elisabeth Tova Bailey lives on the mid-coast of Maine. That’s about all we know of her background in the novel “The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating.” Then, we learn, “At the age of 34, on a brief trip to Europe, I was felled by a mysterious viral or bacterial pathogen, resulting in severe neurological symptoms.”

The pathogen began slowly to eat away at her immune system, severely compromising her heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion. For a time, her bones were more or less turned to mush. Eventually, she had to move from her large house to small studio apartment, capable of little more than lying in bed all day. Often the only person she would see was her caretaker for a half-hour at meals.

Then a friend brought her a little pot of violets, dug from the leafy loam outside Elisabeth’s studio, in which she’d placed a single woodland snail. This small, humble snail ended up becoming Elisabeth’s companion guide and, in a sense, alter ego for a year.

She moved the snail to a terrarium and made it a water dish from the shell of a blue mussel. She boned up on snail nutrition and began feeding the creature bits of Portobello mushroom. She closely observed the snail (which to her everlasting credit she refrained from naming).

She read tomes of botany and biology. She read through philosophy books, haikus, memoirs and early 1900’s hygiene gazettes, poring through them for references to snails.

She discovered all kinds of fascinating facts. She learned that her snail possessed 2,640 teeth that, as Aristotle noted, were “sharp, and small, and delicate.”

She writes, “The teeth point inward so as to give the snail a firm grasp on its food; with about 33 teeth per row and maybe 80 or so rows, they form a multitoothed ribbon called a radula, which works much like a rasp. This explained my snail’s nodding head as it grated away at a mushroom; it also explained the odd squareness of the holes I had discovered in my envelopes and lists.”

Snails, it turns out, not only eat perfectly square holes through paper. They can build a little door for themselves out of mucous and snugly shut themselves in for the winter.

They have an elaborate and seemingly tender mating ritual which in certain snail species involves, I kid you not, the mutual manufacture and launching of “tiny, beautifully made arrows of calcium carbonate” which are stored in a kind of built-in quiver.

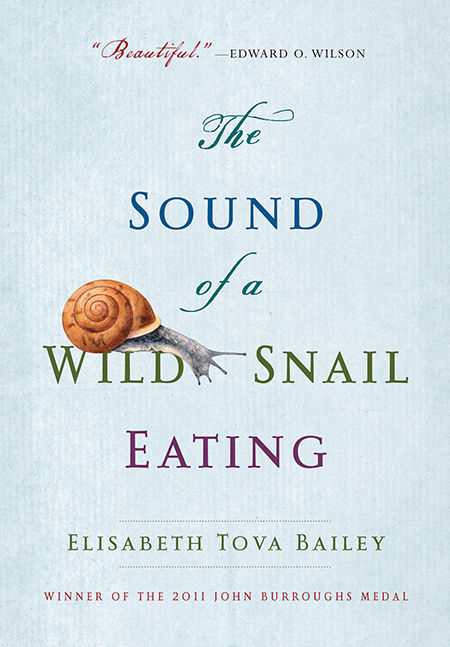

One of my favorite chapters was entitled “Marvelous Spirals.” “Even when my snail was asleep,” Elisabeth writes, “I loved to gaze at the beautiful spiral of its shell. It was a tiny, brilliant accomplishment of architecture, and because the radius of the spiral increases exponentially as it progresses, it fits the definition of a logarithmic or an equiangular spiral.”

All that talk of spirals reminded me of the Loretto Chapel in Santa Fe and the “Miraculous Staircase” I saw there years ago. Constructed without a single nail — only hand-carved wooden pegs — the staircase ascends upward like a chambered nautilus, making two complete 360-degree turns with no visible means of support.

As the story goes, in 1878 the cash-poor nuns who lived in Loretto’s attached convent had realized the planned stairs to the choir loft of the new chapel weren’t going to fit and made a novena to St. Joseph. Within days, an anonymous carpenter rode up on a donkey.

Using only a saw, a hammer, and a square, over a period of six months he built the wondrous spiral staircase. Then he refused all payment, disappeared, and was never seen again.

Like the anonymous carpenter, from her sickbed Elisabeth Tova Bailey worked with the tools at hand. Like the anonymous carpenter, she faded into the background, allowing the lowly but splendid snail to take center stage in the book, a lasting monument to goodness, beauty and truth.

She notes the many similarities between her and her snail: the slow pace at which they move; the fact that they’re both in the process of adapting to changed environments.

As the book progressed, I was afraid the snail would die at the end. Instead, it eventually laid several clutches of eggs and gave birth to 118 baby snails.

After a year, Elisabeth returned the snail to the woods, along with 117 of its children. Then she moved back to her farmhouse, bringing along a single offspring snail.

Her health continued to incrementally improve. “I might retrieve some papers from a few yards away in the late morning,” she notes, “and then in late afternoon I’d try a rash trip around the corner to the kitchen for a fresh glass of water.”

She eventually released that snail as well. Then she went on to study, ponder, and write this small gem of a book.