A 3-1-2 record? Not terrible, but no great shakes, either. And hardly an auspicious debut season for any college football coach, much the less the one who, within a decade, would be acknowledged as the best of his generation.

And, a century later, as perhaps the greatest of all time.

That, of course, would be Knute Larsen Rockne, the coach to whom every one of his successors at the University of Notre Dame is inevitably compared, for Rockne’s .881 winning percentage (105 wins against just 12 losses and 5 ties) remains unmatched by any college coach since.

Sadly, his was a career cut tragically short by an airplane crash that took his life in 1931, following his 13th season. So great was the grief among the nation’s football fans — most of whom had never seen Rockne or his teams except in newspaper photos or newsreel films — that his funeral was broadcast internationally on live radio.

As the Fighting Irish of 2018 seek another national championship, 100 years after Rockne’s first season at the helm of his alma mater, it is as appropriate a time as any to recall the coach still regarded by many as the face of Notre Dame football, familiarly and forever known as “The Rock.”

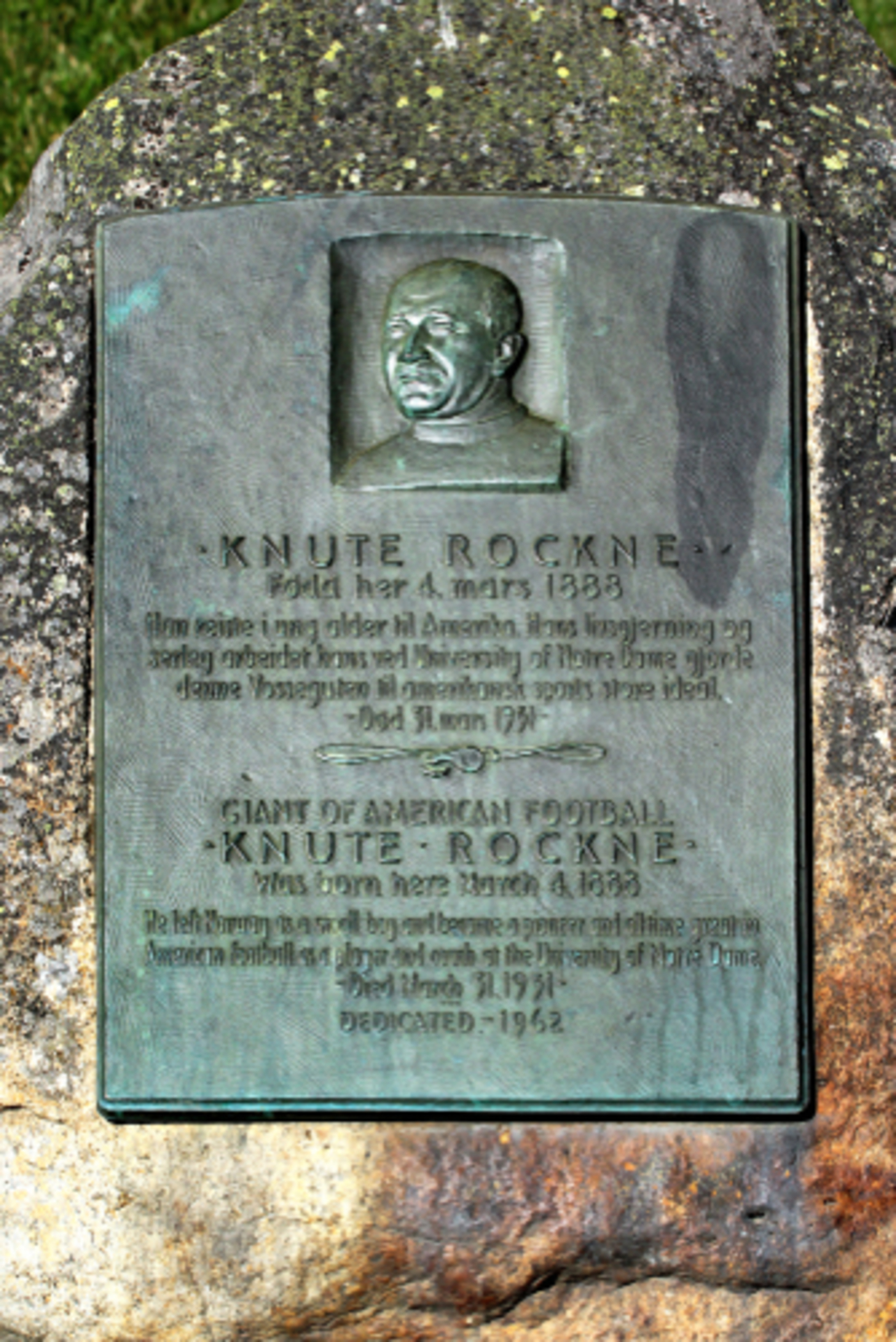

Rockne was born March 4, 1888 in Voss, Norway, and immigrated to Chicago with his parents at age 5. He played football and ran track at North West Division High School, and after graduation became a mailman for four years to save money for college.

He enrolled at Notre Dame at age 22 and became a star end, good enough to be named an All-American in 1913. On Nov. 1 of that season, Rockne helped revolutionize college football when he and quarterback Gus Dorais utilized long passes — up to then, legal but rarely employed by most teams — to rout highly-rated Army, 35-13 at West Point.

Doran later became best man at Rockne’s wedding on July 14, 1914, to Bonnie Gwendolyn Skiles, at Sts. Peter and Paul Church in Sandusky, Ohio. Rockne was Lutheran, but converted to the Catholic faith on Nov. 25, 1925, with Holy Cross Father Vincent Mooney baptizing Rockne at Notre Dame’s Log Chapel.

Rockne earned a degree in pharmacy from Notre Dame and worked as a lab assistant until he was drawn back to football, first to play professionally, and then to coaching various club teams, before being appointed to coach Notre Dame where — as in the 1913 win over Army — he popularized the use of the forward pass.

In his first game as coach — Sept. 28, 1918 at Cleveland — Rockne’s Irish defeated Case (now Case Western), 26-6. Notre Dame also defeated Wabash and Purdue, lost to Michigan Agricultural (now Michigan State), and tied Great Lakes Navy and Nebraska. A worldwide flu epidemic caused cancellation of three other games that season.

Rockne’s first team included future Green Bay Packers coaching legend Curly Lambeau and halfback George Gipp, who in 1919 and 1920 led Rockne’s teams to perfect 9-0 records and unofficial national championships in the “pre-weekly polls” era.

Gipp died of pneumonia within weeks of the end of the 1920 season and, on his deathbed, reportedly told Rockne the words that echoed throughout sports history: “When the team is up against it, when things are wrong and the breaks are beating the boys, ask them to go in there with all they've got and win just one for the Gipper.”

But it wasn’t until Nov. 10, 1928, during halftime of Notre Dame’s battle with unbeaten Army at Yankee Stadium, that Rockne used the line to fire up his team, which then went and upset the Cadets, 12-6. It was the highlight of an otherwise ordinary 5-4 season, which began with a win over Loyola of Los Angeles and ended with a loss to USC, giving the unbeaten Trojans their first national title.

The Notre Dame-USC series, billed as “the greatest intersectional rivalry in college football,” reportedly stemmed from a 1925 conversation between Rockne’s wife and the wife of USC’s athletic director. Rockne supposedly resisted the idea of traveling to the West Coast, until Mrs. Rockne was convinced that a trip to sunny Southern California every two years was better than an annual visit to snowy Nebraska.

Another version of the series’ origin maintains that Rockne, a good friend of USC coach Howard Jones, had no aversion to such travel and — always looking to promote Notre Dame and college football in general — agreed to the series to please Notre Dame’s steadily-increasing alumni in Southern California. The first game in 1926 at the new L.A. Memorial Coliseum saw Notre Dame win, 13-12.

USC nearly played Notre Dame in the Jan. 1, 1925 Rose Bowl, but Stanford, as winner of the Pacific Coast Conference, had first choice and opted for Pasadena. Notre Dame — bristling at Stanford’s reportedly low regard for Catholic school academic programs — won, 27-10, as Elmer Layden (one of the legendary Four Horsemen) scored three touchdowns (two on interception returns), capping an unbeaten (10-0) national championship season.

Because of Rockne, Notre Dame was the first major university to regularly schedule games well-removed from its South Bend home (USC being Exhibit A), thus boosting college football’s national appeal beyond the East Coast and Upper Midwest, which until the late 1920s supplied the majority of All-Americans and national champions.

Rockne is regarded as one of the preeminent figures of sports’ Golden Age of the 1920s, along with baseball’s Babe Ruth, tennis’ Bill Tilden and golf’s Bobby Jones.

His ability to charm the press, advertisers (he was a pitchman for Studebaker) and nearly anyone mildly interested in college football not only led to increased exposure for Notre Dame football, but helped Rockne earn an annual salary of $75,000, millions in today’s economy.

The 1929 and 1930 teams, Rockne’s last, were both undefeated national champions. On Dec. 6, 1930, the Fighting Irish beat USC 27-0 before 73,967 at the Coliseum for its 19th straight win in what would be Rockne’s final game.

On March 31, 1931, after visiting two of his sons at a Kansas City boarding school, Rockne was flying over Kansas when the wings of the Transcontinental & Western Airliner broke up in flight and the plane crashed in a wheat field near Bazaar, Kansas. All eight people aboard, including Rockne, were killed.

The crash elicited a national outcry that led to sweeping changes to airplane design, manufacturing, operation, inspection, maintenance and regulation.

President Herbert Hoover called Rockne’s death “a national loss,” King Haakon VII of Norway posthumously knighted Rockne, and more than 100,000 people lined the route of his funeral procession. The funeral was broadcast on network radio throughout the U.S., Europe and parts of South America and Asia, and Rockne was buried at Highland Cemetery in South Bend, several miles from the campus, as per his widow’s request.

Mike Nelson is the former editor of The Tidings (predecessor of Angelus News).

Start your day with Always Forward, our award-winning e-newsletter. Get this smart, handpicked selection of the day’s top news, analysis, and opinion, delivered to your inbox. Sign up absolutely free today!