As the universal Church prepares to enter Lent at the end of this month, thousands of American Catholics are preparing for another yearly milestone in the life of the Catholic Church in Southern California: the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress, which this year is taking place Feb. 20-23 at the Anaheim Convention Center.

The theme chosen for this year’s congress is “Live Mercy, Be Holy.” For this year’s “Congress issue,” Angelus News spoke to three of this year’s speakers — a bishop serving along the U.S.-Mexico border, a laywoman working for a diocese, and a layman teaching at a prestigious Catholic university — about what this year’s gathering means to them in the context of the Church’s most urgent mission: evangelization.

This is part one of a three-part series.

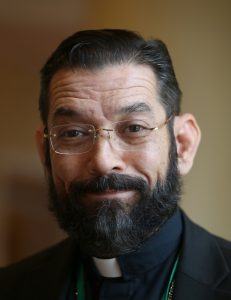

It’s been exactly 10 years since Bishop Daniel Flores was installed as the bishop of Brownsville, Texas, one of the poorest Catholic dioceses in the country.

Since then, he’s earned a reputation among his brother bishops as an outspoken advocate for immigrants, the unborn, and the poor. But the bilingual native Tejano has also shown himself to be one of America’s most articulate thinkers when it comes to talking about the Church’s teachings to a variety of audiences, whether they be Washington, D.C. intellectuals, recently arrived immigrants, or his 5,000-plus Twitter followers.

At this year’s congress (his first), Bishop Flores will preside at a Friday afternoon Mass in English and give a keynote address in Spanish at a worship and praise session Saturday morning.

For this issue, he spoke to Angelus News about what he’s seeing on the border, how patristic theology and detective novels both help him “keep going,” and why he thinks we need to be thinking a lot more about something he calls “disinterested generosity.”

How have you been preparing for the congress, and also for Lent (which starts three days after the congress)? Any good books on your nightstand (or in your suitcase)?

One thing I’ve been doing is meditating more: focusing on the basis of Lent and on the daily Gospels, on hearing the rhythm of the Lord’s words to us these days.

I really take the reality of the daily Gospel of the Mass to be the Lord’s word to us in the Church, and how it comes personally for us on that day. It’s preparatory, but it’s also kind of fun as you get closer to Lent, preparing us for that journey we make with him for 40 days.

I’ve been reading on my iPhone recently the “Tractates on the Gospel of John” by St. Augustine. I go back to that a lot. There are very beautiful expositions of the Gospel of John there, and more recently I’ve been feeling a call to spend some more time with St. Augustine.

When talking about John, St. Augustine goes into the mystery of the glorification of the Son, and I find it very deep and enlightening: how the Church understands the whole mystery of hope. In Lent we enter into this mystery of Christ in his glorification, which also includes his self-emptying.

I always have to have a novel with me to keep going, too. One of the novels I’ve been working on is “The Sixth Lamentation” by William Brodrick, a detective novel that I find to be very deep. He’s very interested in historical memory, especially of the 20th century.

I had read another book of his recently called “A Whispered Name,” set during World War I, which I found very moving, the way he talks about the realities that people faced and questions of faith, because these books deal with that and the questions of God in very dark places.

I think novels can be very helpful in engaging some of those human anxieties and fears and realities that we sometimes don’t want to face.

You hosted Archbishop Gomez and a delegation of U.S. bishops in your diocese in the summer of 2018 for a visit to assess the humanitarian response to the situation on the U.S. - Mexico border. The trip included a meeting with federal officials, a visit to a migrant detention center, and a stop at the Catholic Charities Humanitarian Respite Center. How has the situation on the border in your diocese changed since then?

Since that visit, the government has changed policy quite a bit to what’s known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy.

In the past, a lot of the Central American families that were presenting themselves at border crossings were being allowed to pass into the United States to make their asylum claim, as was the legal requirement at the time. Agencies like Catholic Charities would help deal with those families and get them connected to relatives in the country.

But right now, the “Remain in Mexico” policy requires them to make their petition and then go back to Mexico and wait there for a decision, which could be several months down the road.

So right now, for example, we're directing our humanitarian effort to help these families. Many of our volunteers and people from across the Rio Grande Valley cross the border into Matamoros (which is right across the bridge in Mexico) on a regular basis to help these families who are basically living in tents on the Rio Grande River.

It’s quite a desperate and very difficult situation. I’ve been over there, but the people who see it will tell you it’s a vastly different situation. There are people on the Mexican side living in tents who are waiting for their court date. So the situation has changed in terms of what these families are going through.

As a bishop on the border, you have a front-row seat to some of the harshest consequences of the divisions in this country right now, especially when it comes to the issue of immigration. At times, it seems that this kind of division is also present in the Church, too. What, in a few words, is a Christian supposed to make of times like these?

Our challenge is to let the teaching of the Church, our faith, the Gospel, the person of Christ himself, to be the light by which we organize our politics and our involvement in the political field, and in the political world.

We have to be involved in society, but the Gospel has to be the principal lens through which we judge things. But sometimes — and we aren’t even always conscious of it — we allow our politics to be the lens by which we judge the Gospel. And I think that’s one of the sources of the division within the body of the Church.

As a bishop, what I ask people to do with respect to the “hot-button” issues, whether it's immigration, abortion, or the death penalty, is to look at these issues first in terms of the basic responsibility of a Christian to respond to the human being in front of you with mercy and compassion.

That doesn’t mean that there’s no law or order when it comes to these things, but rather that when it comes to the person we’re looking at, especially the person in distress, that our response should be as to Christ himself. And then we can figure out how to make the policies in a way that expresses that sense of concern and mercy.

But that’s all the way across the spectrum of difficult [political] issues that cause division nowadays. Those are what I call the “human condition issues” of people who are in great distress, like mothers who have difficulty in finding any support in bringing a child into the world, or immigrant parents with children who are afraid they’ll get killed or kidnapped.

We have to respond to that human reality first, and then craft the laws that respond to those things in a compassionate way in which the suffering of the human person does not get eclipsed in our conversation.

That has to be the first thing we think about. That doesn’t mean that we’re going to agree necessarily on the best policies to address these situations on the public level, but at the very least we’re starting from the same starting point, which is to find a way to address these things with compassion.

Within the Church, we also have a special responsibility to treat each other calmly and without rancor, and I think that’s sometimes difficult when political tensions get very, very high.

You shepherd one of the poorest dioceses in the country, and one where there is a remarkable amount of human suffering. Despite this, what do you see that gives you the most hope?

Well, you know that hope is a theological virtue that comes from faith in a God who loves us. I see that evidenced in a lot of very difficult situations in my diocese where people pull together and respond in a generous way to each other: volunteers who give up their time to help families, to wash clothes for migrant children, or mop floors.

Distress can cause us to kind of give up and despair, and say, “Well, the world is a terrible place and I can’t do anything, so I might as well just try to take care of myself.”

But I see a lot of people who are inspirations to me, who just do what they can to help others. Yes, there is suffering and distress. But in Spanish we say, “Los pobres son los más generosos” — that the poor are often the most generous in terms of responding to the situation of somebody else who’s in an even worse condition. That’s what I see, and to me, that’s a sign of how God’s grace can change our response.

We can have hardened hearts, or we can have fleshy hearts — that's the kind of option that the Scriptures give us. If we want fleshy hearts, we have the Holy Spirit to give us that, and then then can we do something. That’s what gives me hope.

Your schedule at the congress includes a “Mass for the Evangelization of All Peoples” and a talk in Spanish on the theme of mercy. What message are you hoping to get across to “congressgoers” this week?

I want to tie in how we live our Christian lives with the themes of evangelization and mercy. I want to approach that from a few different angles because ultimately, our credibility as followers of Jesus, especially in the world today, is inextricably tied to the integrity of our “disinterested generosity,” which is another word for charity.

This kind of love is the response to the human need, a call to alleviate, to the extent we can, the distress of another. It’s our response to Christ, who speaks to us from the cross and through the resurrection so that our hearts are touched by the mystery of love. That’s evangelizing.

Christ says, “Love one another; even as I have loved you.” And it’s that responsiveness to Christ and to the distress around us that are inseparable.

This is so central to the Gospel that we have to find ways to talk about it. But I am convinced that the credibility of the Church depends on whether there is such a thing in the world as a love that gives without asking for payment in return.

This is the key, because the world we live in is very cynical about that. It tends to want to deconstruct everything and even deconstructs love in such a way that there's even a certain sort of cynicism.

If young people, for example, don’t have an experience of generosity around them from very early on, they kind of give up on this love, and basically life becomes all about what you can get out of it and it doesn't matter who you step on to get it.

Jesus says to do good to those who can’t repay you. I think that that’s at the heart of the credibility of the Church’s witness, the witness of grace in the world.

There’s a great need in the Church for us to recover our own sense that there’s something new in the world called the grace of Christ crucified and risen from the dead, and we have to make that visible by our own generosity.