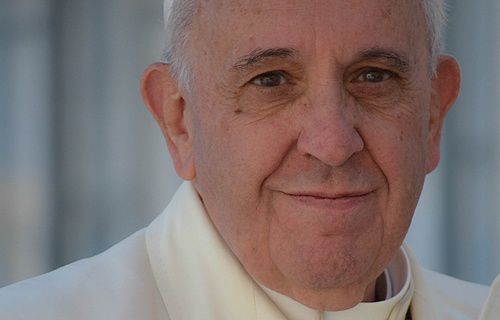

In his new book on mercy Pope Francis offers extensive reflections on the topic that has shaped much of his pontificate, getting personal about his own experiences of mercy, what it means for him, and why humanity is in such desperate need of it.

“This is a time for mercy. The Church is showing her maternal side, her motherly face, to a humanity that is wounded,” the Pope said in his new book “The Name of God is Mercy,” released Jan. 12.

“She does not wait for the wounded to knock on her doors, she looks for them on the streets, she gathers them in, she embraces them, she takes care of them, she makes them feel loved…I am ever more convinced of it, this is a kairós, our era is a kairós of mercy, an opportune time.”

Francis’ comments are part of a book-length interview with Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli. The book is meant to “reveal the heart of Francis and his vision,” according to Tornielli's foreward. He had wanted to ask the Pope about mercy and forgiveness, “to analyze what those words mean to him, as a man and a priest.”

In the Pope’s own words, he says that the meaning of mercy for him goes to the etymological root of the word: “misericordis, which means opening one’s heart to wretchedness.”

“Mercy is the divine attitude which embraces, it is God’s giving himself to us, accepting us, and bowing to forgive,” he said. “Mercy is God’s identity card. God of Mercy, merciful God. For me, this really is the Lord’s identity.”

When asked by Tornielli why humanity is in such great need mercy, Francis simply answered: “Because humanity is wounded, deeply wounded.”

“Either it does not know how to cure its wounds or it believes that it’s not possible to cure them,” he said, explaining that it is not just a question of being wounded by social ills such as poverty or exclusion.

“Relativism wounds people too: all things seem equal, all things appear the same. Humanity needs mercy and compassion.”

Today, he said, we feel that “our illness, our sins, to be incurable, things that cannot be healed or forgiven. We lack the actual concrete experience of mercy.”

“We don’t believe that there is a chance for redemption; for a hand to raise you up; for an embrace to save you, forgive you, pick you up, flood you with infinite, patient, indulgent love; to put you back on your feet. We need mercy.”

He explained to Tornielli that the centrality of mercy in his life has “slowly evolved” over the years through his work as a priest, particularly in hearing confessions, as well as the many “positive and beautiful stories” he has seen.

Mercy is “Jesus’ most important message” Francis said, and, quoting retired pontiff Benedict XVI, added that “mercy is in reality the core of the Gospel message.”

“This love of mercy also illuminates the face of the Church...Everything that the Church says and does shows that God has mercy for man,” he observed.

Pope Francis recounted how the idea to have a Jubilee of Mercy came to him, explaining that the decision “came through prayer, through reflection on the teachings and declarations of the Popes who preceded me, and by thinking of the Church as a field hospital, where treatment is given above all to those who are most wounded.”

He said the first seeds were planted while he was still in Buenos Aires. At one point a roundtable discussion was held with theologians on what the pope at that time could do to bring people closer together.

One of the participants in the roundtable had suggested “a Holy Year of forgiveness,” Francis recalled, saying the idea “stayed with me.”

Reflecting on his own life, Pope Francis said that although he doesn’t remember having a first encounter with mercy as a child, one scripture passage he has always found syntony with is Ezekiel chapter 16.

In the passage, the Lord sees a newborn infant left to die and has compassion on her. He takes her in, anoints her and adorns her, only for her to later become a harlot enamored with her own beauty. In order to remind her of her origins, God placed her “above her sisters,” so that she would remember and be ashamed for what she had done.

God's mercy makes us feel shame for ourselves and our sin, the Pope said, explaining that “shame is a grace: when one feels the mercy of God, he feels a great shame for himself and for his sin.”

Shame is “a grace” that St. Ignatius also prayed for, Francis noted, and pointed to Fr. Gaston Fessard’s book “The Dialectic of the ‘Spiritual Exercises’ of St. Ignatius,” which he called “a beautiful essay by a great scholar of spirituality,” on the topic of shame.

He also pointed to a specific confession he had at the age of 17 on the Feast of St Matthew with a priest named Carlos Duarte Ibarra as being especially impactful.

Fr. Duarte is one example that Pope Francis pointed to as a merciful priest, and said that others he has met include Fr. Enrico Pozzoli, the Salesian who baptized him and married his parents, as well as a young Capuchin priest he met in Buenos Aires.