I first encountered the work of San Francisco-based photographer John Chiara at a current exhibition at the Getty: “Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography.”

Chiara’s cameras are old-school: a box with a lens. They’re also huge. He makes them himself and transports them on a custom-made flatbed trailer.

“Basically I have to find someplace I can roll up, parallel park and somehow get the camera in a position to take a photograph.”

He literally climbs inside the camera, which he affectionately describes as a “suffocation box.” “I’ve kind of made photography as labor intensive as I think it could be.” He usually manages but one photo a day.

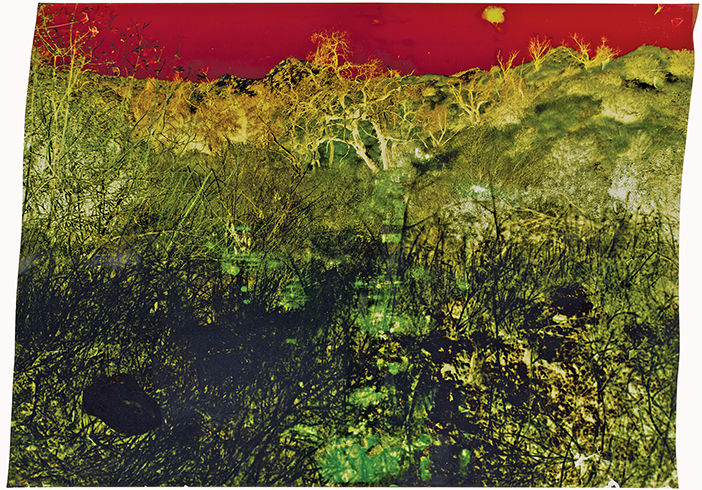

He uses no light meter, no stopwatch, no film. The images, printed directly onto photographic paper, leave serendipitous traces of the process: striations, spots, tiny messages from afar that could be rogue birds, random UFOs or lost mosquitos that bumbled into the suffocation box.

He’s done series on the Bay Area, the Northern California Coast and Los Angeles.

Recently, he spent a year traveling back and forth to Mississippi, absorbing its folklore, its people, its fields, streets, deltas.

The result is a solo show — “Mississippi” — at Bergamot Station’s Rose Gallery through Sept. 5.

Chiara likes to frame views that aren’t necessarily “grand” or “picturesque.” The photos, taken during 2013-2014, contain no antebellum plantations, no Spanish moss, no former lynching sites.

“I find myself photographing the way the light is hitting the inner branches of trees at a particular moment. Because I thought I saw history in there … I sensed meaning in its reflection of this place.”

The works in “Mississippi” are big: 30 to 53 inches wide, 28 to 53 inches tall.

The colors are pale mauve, milky sea green, mother of pearl, dove gray, saturated gold, incandescent sapphire, flashes of pure white light exploding from an “ordinary” stand of trees, a “humdrum” dirt road.

The edges of the photos are irregular, meandering, as if cut by a child trying out scissors for the first time. Many bear the image of wide swaths of cellophane tape, tangled in places, the lovely transparencies darker when doubled, like the wings of dragonflies. And who knew you could get lost in the beauty of a pattern of trapped air bubbles?

There are no humans. Humans would be out of place. But humans hover mute just outside camera range; their presence sensed if not felt.

“Martin Luther King at de Soto” is all angles: a faded asphalt parking lot, a washed-out sky, a white wall with the outline of what may or may not be a human torso.

In “Highway 1 at Friar’s Point, North,” two (at least) exposures are overlain: the upper one paler, the lower, brighter one out of focus. Swaths of trees, partly shrouded in shadow, recede to wraith-like branches dissolving into the sky.

A diaphanous American flag in “Sanderson at Corporation” dissolves, goes up in smoke, topples into an amethyst sky. At bottom left levitates a small ghostly blue-green half-globe: a new planet? In the background flit tiny protoplasmic blobs of hot pink, jet-black sunspots, an electric-blue amoeba.

The sky-obsessed images in “Mississippi” somehow remind me of J.M.W. Turner’s broodingly majestic sea paintings.

Or maybe they’re more like mirrors.

What’s the big deal? you ask at first glance of “Delta at 1st West.” A washed-out, over-exposed photo of the kind of industrial urban landscape we’ve seen so much of we tend to subconsciously block it out: not beautiful, not noteworthy, not interesting. A no-man’s land — L.A. is full of them — in which stolen goods get fenced and cars get rebuilt.

Then you see the composition is weirdly arresting: the poignant geometry of a garden-variety grouping of telephone poles; a nimbus of otherworldly light settling gently, like a flying saucer, on an aluminum roof. This moment in time. This eye, this angle, this cosmos, this sun.

Or as Chiara describes his work: “The blended character of memory in relation to specific moments or places.”

Standing before “Old River Road at US 1,” 2013, I wonder: Did I forget my glasses? Am I looking at a reflection of trees in a pond? Was this photo taken by God? A sense of vertigo, skewed perception, entering into or lifting off into another world.

Chiara’s photos evoke terror in the original sense of the word: awe, fear and the urge to fall to our knees before what is unknowable.

In “Old Levee at Burkee,” 2014, a stubbly brown field with a stand of bare trees manages to spawn an air of clownish menace crossed with archangelic hope.

I’m not quite sure, if I entered those woods, whether I’d find a bloody crime scene, or Jesus, who would call me by name and give me the verdict on whether I’m to go with the sheep or the goats.

Peter, James and John climbed Mount Tabor. But Chiara’s work reminds us that if we only have eyes to see, the whole world — every inch — is transfigured with tragicomic meaning and mystery.

I first encountered the work of San Francisco-based photographer John Chiara at a current exhibition at the Getty: “Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography.”

Chiara’s cameras are old-school: a box with a lens. They’re also huge. He makes them himself and transports them on a custom-made flatbed trailer.

“Basically I have to find someplace I can roll up, parallel park and somehow get the camera in a position to take a photograph.”

He literally climbs inside the camera, which he affectionately describes as a “suffocation box.” “I’ve kind of made photography as labor intensive as I think it could be.” He usually manages but one photo a day.

He uses no light meter, no stopwatch, no film. The images, printed directly onto photographic paper, leave serendipitous traces of the process: striations, spots, tiny messages from afar that could be rogue birds, random UFOs or lost mosquitos that bumbled into the suffocation box.

He’s done series on the Bay Area, the Northern California Coast and Los Angeles.

Recently, he spent a year traveling back and forth to Mississippi, absorbing its folklore, its people, its fields, streets, deltas.

The result is a solo show — “Mississippi” — at Bergamot Station’s Rose Gallery through Sept. 5.

Chiara likes to frame views that aren’t necessarily “grand” or “picturesque.” The photos, taken during 2013-2014, contain no antebellum plantations, no Spanish moss, no former lynching sites.

“I find myself photographing the way the light is hitting the inner branches of trees at a particular moment. Because I thought I saw history in there … I sensed meaning in its reflection of this place.”

The works in “Mississippi” are big: 30 to 53 inches wide, 28 to 53 inches tall.

The colors are pale mauve, milky sea green, mother of pearl, dove gray, saturated gold, incandescent sapphire, flashes of pure white light exploding from an “ordinary” stand of trees, a “humdrum” dirt road.

The edges of the photos are irregular, meandering, as if cut by a child trying out scissors for the first time. Many bear the image of wide swaths of cellophane tape, tangled in places, the lovely transparencies darker when doubled, like the wings of dragonflies. And who knew you could get lost in the beauty of a pattern of trapped air bubbles?

There are no humans. Humans would be out of place. But humans hover mute just outside camera range; their presence sensed if not felt.

“Martin Luther King at de Soto” is all angles: a faded asphalt parking lot, a washed-out sky, a white wall with the outline of what may or may not be a human torso.

In “Highway 1 at Friar’s Point, North,” two (at least) exposures are overlain: the upper one paler, the lower, brighter one out of focus. Swaths of trees, partly shrouded in shadow, recede to wraith-like branches dissolving into the sky.

A diaphanous American flag in “Sanderson at Corporation” dissolves, goes up in smoke, topples into an amethyst sky. At bottom left levitates a small ghostly blue-green half-globe: a new planet? In the background flit tiny protoplasmic blobs of hot pink, jet-black sunspots, an electric-blue amoeba.

The sky-obsessed images in “Mississippi” somehow remind me of J.M.W. Turner’s broodingly majestic sea paintings.

Or maybe they’re more like mirrors.

What’s the big deal? you ask at first glance of “Delta at 1st West.” A washed-out, over-exposed photo of the kind of industrial urban landscape we’ve seen so much of we tend to subconsciously block it out: not beautiful, not noteworthy, not interesting. A no-man’s land — L.A. is full of them — in which stolen goods get fenced and cars get rebuilt.

Then you see the composition is weirdly arresting: the poignant geometry of a garden-variety grouping of telephone poles; a nimbus of otherworldly light settling gently, like a flying saucer, on an aluminum roof. This moment in time. This eye, this angle, this cosmos, this sun.

Or as Chiara describes his work: “The blended character of memory in relation to specific moments or places.”

Standing before “Old River Road at US 1,” 2013, I wonder: Did I forget my glasses? Am I looking at a reflection of trees in a pond? Was this photo taken by God? A sense of vertigo, skewed perception, entering into or lifting off into another world.

Chiara’s photos evoke terror in the original sense of the word: awe, fear and the urge to fall to our knees before what is unknowable.

In “Old Levee at Burkee,” 2014, a stubbly brown field with a stand of bare trees manages to spawn an air of clownish menace crossed with archangelic hope.

I’m not quite sure, if I entered those woods, whether I’d find a bloody crime scene, or Jesus, who would call me by name and give me the verdict on whether I’m to go with the sheep or the goats.

Peter, James and John climbed Mount Tabor. But Chiara’s work reminds us that if we only have eyes to see, the whole world — every inch — is transfigured with tragicomic meaning and mystery.

John Chiara: “Mississippi” is at the Rose Gallery through Sept. 5.Bergamot Station Arts Center, 2525 Michigan Avenue, G-5, Santa Monica, CA 90404Hours: Tuesday-Saturday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.