On Sept. 15, 2020, as workmen were clearing away rubble from the baptistry of the fire-wrecked Mission San Gabriel, they found something under the burnt timbers and plaster that startled them.

There in the debris, underneath a burnt crossbeam, was a painting showing the Virgin Mary in dark clothes in front of a foreboding dark landscape: Our Lady of Sorrows.

Amazed, they went and found the mission director, Terri Huerta. The timing of the discovery, she immediately realized, could not have been more appropriate.

“My God,” she exclaimed. “This is the feast day of Our Lady of Sorrows.”

The painting, in fact, was the only one in the church that survived the mysterious July 11 fire. Most of the mission’s priceless paintings and sculptures had been removed months earlier for restoration work in anticipation of the mission’s 250-year jubilee celebration planned for next year. Only Our Lady of Sorrows, hung above the baptistry, had been left exposed.

And she survived, despite some holes and blistering around her clearly Hispanic “morena” (“brown-skinned”) face. The insurance company has pledged to restore her, along with any other damage to artwork suffered from the fire.

The surprise discovery comes as a small, seemingly miraculous silver lining in a devastating episode of the mission’s history. So has the more than $200,000 raised through donations to help rebuild the mission.

Investigators are still looking into the possibility of arson, not yet proven, though, according to Jill Short of the Archdiocese Construction Department, “No one has been able to link it to an accident, like an electrical short.”

After 2 ½ months since the fire, reconstruction, not to mention restoration, has yet to begin. For now, the process remains in the debris clean-up phase.

“The damage to the roof, which is pretty much gone, the walls, the choir loft and altar, the ceilings all blackened and charred is pretty substantial,” Huerta said.

There is no dollar estimate yet of costs for the rebuilding, though the team thinks it will take at least a year to complete. As a result, the jubilee festivities next fall may need to take place outside the church.

I asked Huerta if the painting of the dark-clad Lady of Sorrows was the one famously unfurled to the Tongva Indians nearly 250 years ago, on Aug. 15, 1771, the feast of the Assumption, just as San Gabriel was being founded by the Franciscans.

Franciscan missionary Father Francisco Palou described the scene in his 1785 biography of St. Junípero Serra, “Relacion,” writing that the Tongva were “conquered by that beautiful image” displayed to them by the Spaniards.

“They threw down their bows and arrows and the two chiefs rushed forward to place at the feet of the Sovereign Queen the beads they wore around their necks to show their great esteem,” wrote Father Palou.

“They called together the Indians of the nearby villages, whence a growing number of men, women, and children came to see the Most Holy Virgin. They came bearing various seeds which they placed at the feet of the most Blessed Lady, thinking she would consume them as other humans did.”

In a word, so effective was the expression of sorrow, the Tongva thought the image alive.

That image, however, was not the one found in the rubble, but rather one that was removed from the church before the fire, Huerta explained. Would I like to see it? She didn’t have to ask twice.

So, in a sense, there are two miracles at Mission San Gabriel, one in 1771, the other in 2020, each involving a different “La Dolorosa” (“Lady of Sorrows”).

To further complicate things, Father Palou related another painting, one of the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, that so amazed the Kumeyaay in San Diego around the same time that their women tried to nurse the baby, again thinking the image was real. Its whereabouts are unknown.

I inspected the smaller “La Dolorosa” unfurled for the Tongva. It is quite striking. Mary’s eyelids hang down her eyes, themselves in shadow, there are clear tears on her cheek, and her hands are clasped, praying.

It wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine that the Tongva saw Mary begging, rather than praying. Father Palou’s “triumph” may have been more empathy and desire to help rather than powerlessness. Mary’s lips are full, swollen from grief.

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Diva Zumaya, who conducted a recent inventory of the mission’s artwork, the two “La Dolorosas” date back to the 18th century, though exact dates and the artists have not yet been determined. Zumaya also believes the “La Dolorosa” unfurled for the Tongva has been heavily painted over.

The grief Angelenos have experienced since learning that the literal birthplace of Los Angeles was nearly burned to the ground will take some time to be restored, too. Meanwhile, the bricks and mortar call.

The intense heat of the fire twisted the steel beams installed as part of a retrofitting after the 1987 Whittier Narrows earthquake. The roof itself, made of wood, is almost completely gone, with only some bits of insulation chicken wire hanging from the few black crossbeams that didn’t fall.

There has been discussion about what kind of roof will replace it, as well as the threat posed by the nearby, and potentially flammable, palm and pepper trees on the mission grounds.

There is also damage from the firefight itself to contend with. When firefighters hacked through the south-facing door the night of the fire, they did so strategically, using a chainsaw rather than axes to cut a tall rectangle in the wood to reach and open the door.

But the water from the fire hoses left a mark: the baptistry’s tiled flooring, which sank several inches from trapped water, must be repaired, as well as the sacristy’s floor, which fell 6 to 8 inches.

An archaeological dig as deep as 3 feet will take place in both places, in partnership with Native American monitors (as law requires). Could Tongva remains be there? Huerta said no one knows for sure, but Tongva Indians are buried in the “camposanto” (“cemetery”) outside, though there are no records as to who they are or how many.

Statues of the top three of the six saints in the “reredos,” a large altarpiece above the altar, were damaged badly. These were St. Gabriel, St. Anthony, and St. Dominic; the three that escaped injury were the Immaculate Conception, St. Francis, and St. Joachim. Murals of the four evangelists — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — in the four corners of the baptistry, need to be cleaned and possibly restored.

Huerta says the long-delayed restoration needs will “piggyback” onto the reconstruction and repair to take advantage of the general shutdown of the mission. In addition to the painting, restoration work will be tackling another surprise finding after the fire: The curious layers of coral and red paint near the altar that reveal serpentine, squiggled patterns underneath.

“The best example of original artwork and patterns found under a drab interior were found at Mission San Miguel,” said Mel Green, the lead structural engineer for the rehabbing of Mission San Gabriel. “There’s got to be something underneath the dull paint of the mission walls that we could find and bring out.”

Huerta is going to keep as a display some of the missing plaster to show the stonework underneath. The south door that let in the firefighters can be restored.

Some red glass on the doors in the back of the church near the choir loft may be changed in color. All such changes must be approved by the San Gabriel Historical Commission.

Some exploratory work may be done on the north-facing wall, where there has long been speculation there was an original niche or windows covered up (or “Victorianized,” according to Short) during the secularization period. Originally with domes, it then went to a flat roof, and finally was gabled in the late 19th century.

Great art, and devotion, always seemed to rise out of San Gabriel’s ruins. Traditionally, there are seven “sorrows” associated with Our Lady of Sorrows: Mary’s heart pierced at the prediction of Jesus’ fate at his presentation in the Temple; the flight into Egypt fleeing Herod; searching for a lost Jesus in Jerusalem; meeting him on the road to Calvary; standing at the cross; receiving Christ’s body; and finally, the burial of her Son.

There was certainly sorrow during the early years of Mission San Gabriel’s inception for Our Lady of Sorrows to redeem. Besides the earthquakes and this fire, St. Junípero wrote to the Spanish viceroy at the time that “a plague of evils” had broken out in San Gabriel, desperate to turn it around.

Nevertheless, on Oct. 11, 1771, when fires burned across the Los Angeles basin and it seemed as if the Tongva were preparing a major attack, two chiefs came to the mission to sue for peace, stunning Fathers Pedro Cambon and Angel Somera, who asked for a transfer due to soldier transgressions.

Fathers Antonio Cruzado and Antonio Paterna, who relieved them, managed to slowly win back Indian trust, and Mission San Gabriel went on to be the richest and most productive of all the missions, with vast vineyards (the first in California were not in northern California, but in Los Angeles), 16,500 head of cattle, and a horse farm of 1,200.

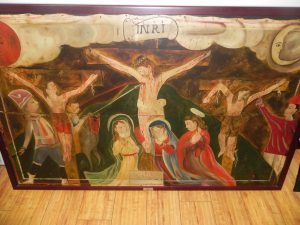

By 1817, 1,700 Tongva, Serrano, and Cahuilla Indians lived and worked at Mission San Gabriel, producing large vegetable gardens that kept the entire mission chain alive, including the Indian residents and some in the villages. It is fitting that the finest works of Indian art from the mission era, the 14 Stations of the Cross, now live at Mission San Gabriel, thankfully, under lock and key.

The Tongva artist painted the Roman soldiers who tortured Christ as Spanish “comandantes” (“commanders”), while Christ and Mary resemble California Indians. The Twelfth Station of the Cross is extraordinary: The bad thief on Christ’s left who looks away from the Savior is slumped on his cross, as if poorly tied with rope. But the good thief has his arms thrust exactly as Christ’s — upward — and he is nailed just as Christ. His gaze to Jesus is loving.

With so much to be done and decided ahead of the mission’s jubilee celebration next year, Huerta sees last summer’s fire as a part of a bigger plan.

“We want Mission San Gabriel to be a place of healing,” she said. “That we found ‘La Dolorosa’ in ashes but surviving on her own feast day, it’s encouraging! We have been on this journey at San Gabriel for a long time, first to renovate and improve the property for the jubilee celebration of 250 years, and now this tragic fire.

“The end result is that it is going to look more glorious.”